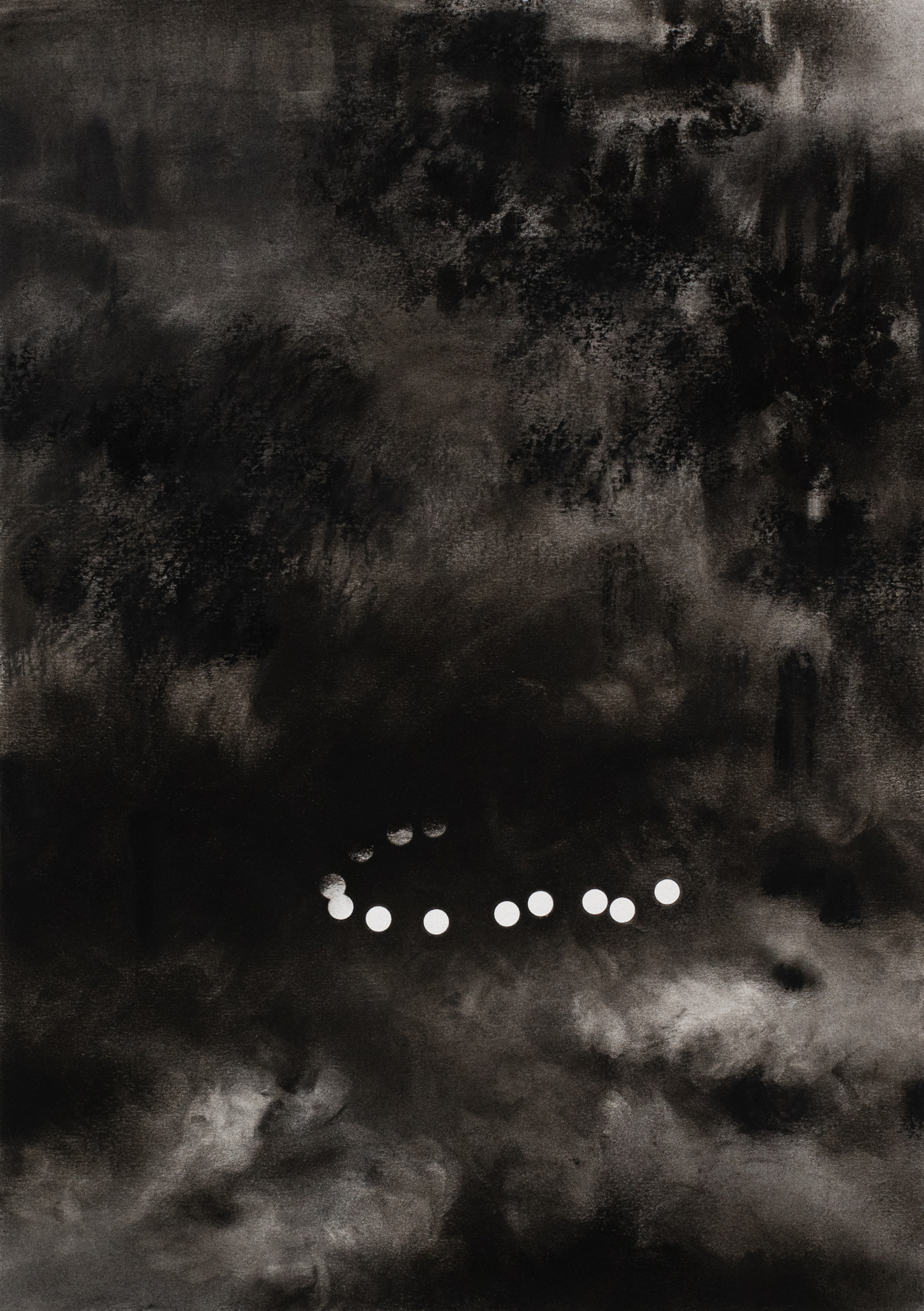

Lisbon-based artist Diogo Costa spreads a fine layer of charcoal over a blank sheet of paper and softly blends it, moving the palm of his hand over the surface until subtle black traces emerge: the foundation of his drawings, which he later completes with perfectly delineated circles. Balancing intuition and precision, the act of looking and being looked at, his work seeks to become a space where he can lose control over the material, and over himself.

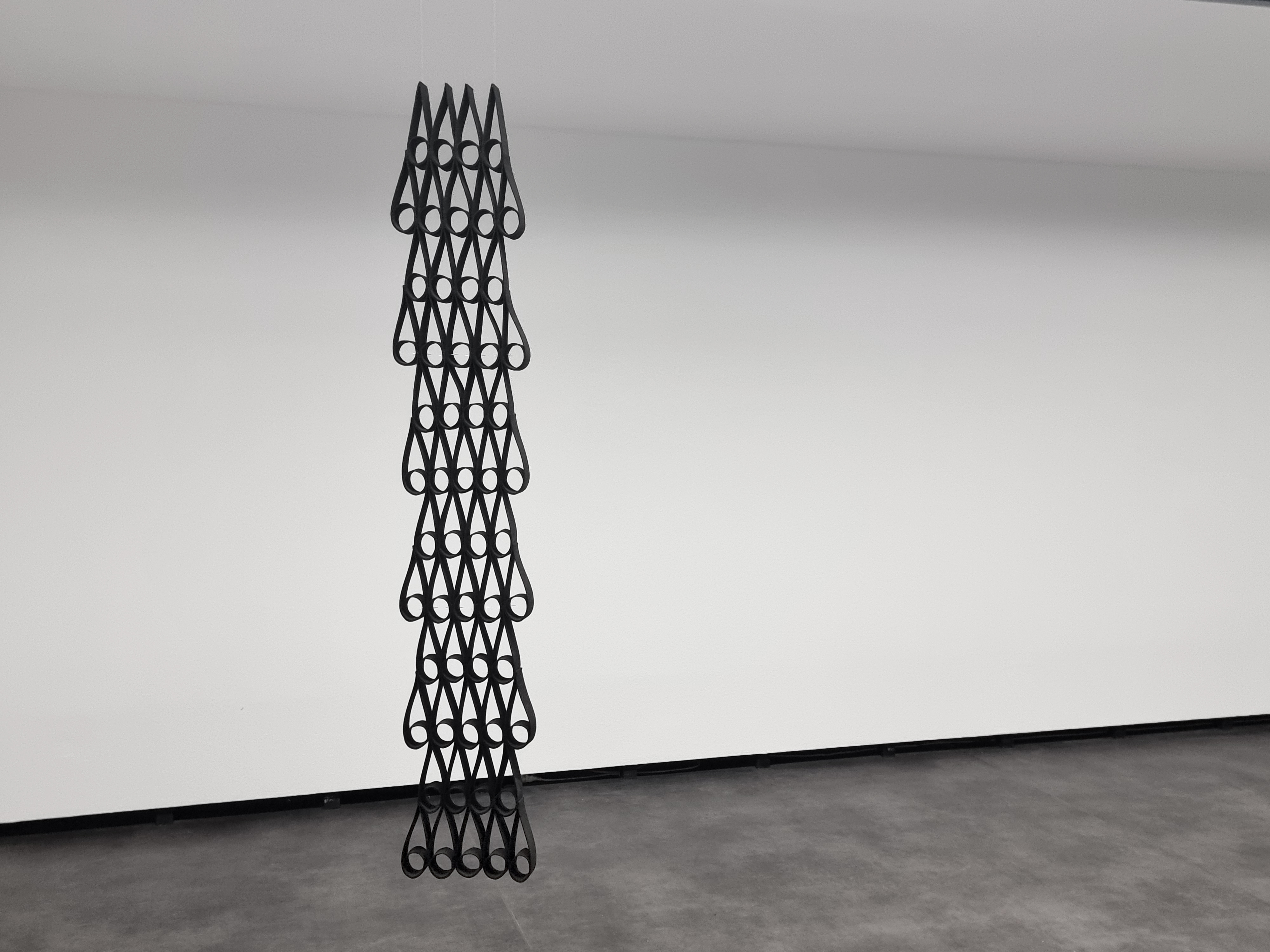

So, I am in residency at LEA, Lab of Experimental Art, in Madrid. Here, I decided to make a group of drawings and one of sculptures, in order to try to articulate two bodies of work. These sculptures or expanded drawings are related to “celosías”, which in Portuguese would correspond to reticulated screens or lattices. It is an architectural element built into houses and buildings, whose function is to separate the interior from the exterior, and which is usually made of metal, wood or brick. These are perforated or hollowed walls that allow privacy for those inside, while making it possible to look outside without being seen.

I decided to start the project by walking around the city and taking several photographs. What I found most present in the city, and which seemed very characteristic of Madrid and different from Portugal, is that most windows or doors are covered with grilles. These grilles can have more or fewer ornaments according to the period in which they were made or their historical context. They may resort to drawings or notions of rhythm and form in a more geometric sense, at times, or have motifs, drawings or more figurative shapes. They vary according to the part of the city, ranging from more simplified or minimalist compositions to much more elaborate, dense and ornamented elements.

Were you also interested in carrying out a sociological investigation of these differences?

I think I was doing it unconsciously. As I moved through different neighbourhoods of the city, I began to notice variations in these grilles and railings. In older areas of the city, and in others that, by their appearance, seemed associated with royalty and an upper class, there was a greater presence of ornamentation.

On the contrary, in other neighbourhoods of more recent construction, I noticed a smaller presence of figuration and a more modern influence, where the morphology of the drawing itself seems more present, with geometric shapes and a certain sense of rhythm imposed through the way the lines of these railings generate repetitions of more simplified shapes.

But I believe it would be necessary to analyse this in greater depth in order to extract correlations between aesthetic expression and sociological contexts.

For this project, you mentioned you were interested in exploring the idea of “seeing and being seen”. Could you elaborate a little more?

It relates to a reflection on the act of experiencing art, or engaging with an artistic object, particularly when that object is static and not based on a sequence of moving images. In those situations—or at least in my personal experience—our inner world becomes much more present and perceptible. Thoughts, sensations, emotions, and perceptions seem to surface with greater clarity.

I’m drawn to the idea that an artistic object can contain within it the potential to activate self-awareness through silence, assuming there is a willingness on the part of the viewer to enter that space.

You walked through Madrid in search of the object of your study. Is wandering around cities something you usually do to spark inspiration?

I enjoy visiting exhibitions and spending time outdoors as ways of activating inspiration, but yes, I think this attentive way of noticing everyday elements is very much part of my process. The grilles, metalwork and sheet-metal structures on windows and balconies repeatedly appeared along my daily routes and held a certain magnetism for me. Whether through their designs or through their condition as prosthetic elements attached to buildings—marking a boundary between interior and exterior—they began to generate a kind of affect, or perhaps an affectation, that led me to observe them more closely and to develop an ongoing inquiry around this motif.

It is striking to touch the felt you use in your sculptures before and after you treat it—it truly transform from textile into something rigid and three-dimensional. What draws you to this material?

I think my choice of material is closely linked to the intention of not dazzling the eye or overstimulating it, so as to leave space for the internal experience that can occur on the viewer’s side when interacting with the artwork. I was drawn to felt precisely because of its qualities, where a certain modesty is implicit. These felt works tend toward the kind of mystery that darkness brings, which feels appropriate for channelling ideas of interiority—something that can become more evident or heightened depending on the material used.

I like to think about the material of these sculpture-drawings both functionally and metaphorically. Felt is versatile and conveys warmth, as well as a tactile quality intrinsic to textile materials. Its usual association with clothing, with covering, warming or hiding, is something that interests me and that I connect to notions of intimacy.

In your technique there is a contrast between very different approaches: the loose, intuitive charcoal base and the precise dots created with stickers. Why does this mixture attract you?

This contrast has to do with bringing two seemingly distinct modes of working into dialogue. One is highly premeditated—the placement of the stickers, which later become dots through their removal. The other is the dragging and layering of charcoal, which is far more improvised, as the material lends itself to accident. In the encounter between these two ways of acting, an ambiguity and a certain intensity emerge.

The process begins with a white sheet of paper and circular stickers of various sizes. I interact with the surface as if it were a space with depth, moving from what feels distant to what feels closer. As the image starts to reveal itself, the layers of charcoal gradually increase. When the stickers are removed—one of the final stages of the drawing—white circles appear, opening up the image through the illusion of partial concealment.

Your drawings and paintings seem to evoke an almost dreamlike landscape, don’t you think?

Yes, and it’s even common for me to dream about the works themselves. The behaviour of charcoal as a material seems to facilitate this dreamlike atmosphere. When charcoal is sprinkled onto the paper, it begins to “snow” over the surface. From the very first contact, it leaves marks that do not necessarily come from my hand, but from gravity itself—creating stains and traces that are already evocative from the outset.

In painting, I work in a similar way. I use large brushes with acrylic and oil paint, and throughout the process I deliberately undo the brushstrokes using water and turpentine. I usually begin with acrylic, creating a tonal base that influences the temperature and ambience of the space, or of the imagined landscape, before applying subsequent layers of colour. I paint and unpaint, seeking an encounter between my personal mark and the organic, flowing behaviour of the paint.

In drawing, which I usually do on the floor, there is a moment when I lift the paper and place it vertically to view it from a distance—often when I feel particularly drawn to do so. At that point, a significant amount of loose charcoal falls away. There is always a constant adjustment between the mark made and the material’s behaviour, between an image that has formed and one that is still emerging.

In a way, it seems that you want to lose control of the piece—to let the material assert itself.

That is exactly what I want. And also to lose control of myself.

So, for you, this technique is a way of letting intuition take over, or of suspending more rational modes of making?

Yes, though with varying degrees of intensity. There is a continual back-and-forth between planning and composing, and then letting go of that control—something the material itself actively supports.

You work across three very different areas: painting, drawing and installation. How do you decide which practice to engage with at a given moment?

I think of my practice as a series of islands that, over time, may or may not form archipelagos. I’ve always been inspired by multidisciplinary artists who didn’t focus on a single medium, or whose work evolved through very distinct phases. I believe that, eventually, these islands begin to communicate with one another in unexpected ways.

This also comes from my own working habits. I keep several notebooks where I write down ideas, sketch pieces, or draw images that appear in dreams or vivid everyday thoughts. Revisiting these notebooks often generates new works and connections. Looking back, my more recent work with felt emerged partly from a crossing of earlier notebook drawings with my experience of shaping brass strips in a metal workshop in Lisbon, and from an unexpected encounter with a large piece of felt hidden inside a roll of canvas I took to an artistic residency at RAMA – Art Residencies in Maceira, Torres Vedras. Through chance encounters and affective relationships with materials, objects or everyday events, new threads often appear and lead to further connections.

By removing objects from their usual context and including them in your installtions, are you trying to surprise the viewer? Or invite them to think beyond their habitual associations with that object?

Yes. Certain common objects find their way into a sculpture or installation through an encounter, often because there is a sense that they already carry a latent poetics. The egg is a good example. During a period when my aunt had chickens and would send eggs to my parents, I remember some cardboard boxes containing eggs that were unusually bluish or greenish—sometimes smaller, rounder or more elongated. I began to notice them more closely and to appreciate their differences.

That initial fascination gives rise to questions about how I’m seeing the object, and about the ambiguity or strangeness it may already contain. When this happens, even without fully understanding why, I bring the object into the studio. Often, simply having it nearby generates relationships that materialise in drawings and lead to new works. By displacing the object or situating it within an installation—through positioning, lighting, or modes of presentation—I try to emphasise this poetic dimension and establish a subtle contact with the viewer through surprise or nuance.

In some installations, there is a strong tension between opposing elements—for example, the egg placed on a rectangular surface, on the verge of falling but not falling. What attracts you to these moments of suspension, these “before the fall” situations?

It’s a question I hadn’t articulated so clearly before. I suppose there is room for projection, both on my part and on the viewer’s, as well as an interest in suspension—an “in-between” moment. By testing tensions or oppositions, and exploring the relationships they generate, certain qualities intensify, cancel each other out, or complement one another through their coexistence.

Do you think the objects that attract you have something in common?

I think they are all objects that, in some way, carry a space—one that can unfold into many facets. It might be a mental space, or something that triggers memory or emotion. I’m drawn to objects that have the capacity to contain.

Perhaps it’s just my impression, but I sense a touch of humour in some of the works, especially the installations.

Yes, though I wouldn’t describe it as laughter. It’s more a sense of playfulness—a game, a pun, a trap.

Artists you admire?

There is an artist I deeply admire and who inspires me greatly: Haris Epaminonda. I also find Ana Jotta incredibly inspiring—an essential figure for younger generations because of her intellectual honesty, her relationship to process, and her sense of play and lightness. John Baldessari as well, particularly his dots series and his strategy of omitting what one expects to see, although my approach to that idea is quite different.

What is the process of bringing these pieces to life in the exhibition space like? Is it site-specific?

I would say that the characteristics of the space are important, but I approach them in a more theatrical or scenographic way. Rather than responding strictly to the site, I am interested in transforming it—creating another space by working with what already exists. Within this intention, there is a desire to open up the viewer’s perception: to slow the gaze down, to divert it, or to shift it altogether.

Three-dimensional or sculptural forms have the advantage of requiring the visitor to move, to walk around the works, thus activating their own movement through space. This also connects to a broader reflection: linear perspective was conceived for a single, fixed point of view—a body standing still, looking forward—and for a representational system that produced a convincing illusion of reality. For centuries, it was believed that this was how we see.

In reality, our heads move, our eyes wander, our bodies shift, and vision emerges from a combination of senses. Seeing is not merely a retinal experience; it happens from the inside out as much as from the outside in. By working with spatial compositions that engage the visitor’s movement, it becomes possible to activate memory and imagination as well—playing with the fact that when we turn our backs, we lose certain information in order to access something else. There is a form of walking or wandering that can be encouraged by my decisions, but also shaped by the spectator’s own choices and subjective gaze, which ultimately becomes an element that completes the aesthetic experience.

I was reading a text about the flâneur, a figure who politicises everyday objects and spaces through observation and is able to signal cracks in the system. Do you identify with this?

Yes, naturally. I like to live in this way. It is not even a conscious decision—I simply experience everyday life by allowing my gaze to wander, stepping out of a certain automatism. As if seeing could happen for the first time, opening up the possibility of noticing things that give rise to questioning or critique.

Many Portuguese artists express concern about the lack of institutional, economic or social support in the country. Do you share this view?

Yes, and I find myself constantly—perhaps unconsciously—comparing the place I come from with the place where I am now. This comparison reveals similarities, differences and, above all, a question of scale that reinforces the sense that there is still a significant lack of opportunities and investment in Portugal. This scarcity has a toxic effect on the artistic community and on society more broadly.

The lack of opportunities often pushes artists into competition when cooperation could instead strengthen the community and make it more demanding and resilient. When strong communities and collaborations do emerge, their capacity to generate cultural activity is remarkable, especially considering the effort required to do so under such conditions. Creativity will always persist—because those who live from it often know no other way—but it does so with much greater difficulty and precariousness, a situation that is not exclusive to the arts.

There is also a wider lack of investment across social classes. Many people feel a genuine desire to engage with the culture of their country, but lack the time or energy due to labour structures that prioritise survival over access to cultural life. In Portugal, there is an expression—“he is an artist”—often used disparagingly, as if referring to someone inconsistent or unreliable. I do not identify with that at all. Artists are multifaceted individuals: they lecture, teach, create, manage administrative tasks, study, write, research, design and often combine all of this with other jobs. They sustain their practice through determination, focus and a deep love for what they do, while navigating adversities and structural injustices that extend well beyond the artistic sector.

In that sense, society sometimes still seems to view artists as separate from political positions or views. Do you think it is important to challenge this stereotype of the “mad genius” outside society?

Absolutely. Especially because politics encompasses far more than what appears in the news or within party structures. Politics operates from the smallest gesture to the most expansive systems; it is embedded in everyday life and in local forms of power. I don’t see artists as “mad geniuses”, but as ordinary people driven by passion and a certain obsession with their work and research. They defend freedom and the right to create, and uphold art as a form of kindness, continuing to believe in its transformative power—values I find increasingly vital in our time.

Wrapping things up - how did you experience the residency here at LEA?

It was an intense and deeply enriching adventure, one that opened up new horizons for both my practice and myself. I encountered a wide range of experiences that felt genuinely meaningful. I was particularly moved by the generosity of my colleagues and the strong sense of camaraderie and community, which I carry with me with great gratitude.

It was also an experience of stepping outside my comfort zone, but doing so with focus and integrity—allowing myself to work hard and fully inhabit the experience. Despite the discomfort that often accompanies artistic residencies, I felt welcomed by the space and by the people around me. Meeting others, learning from them and being affected by their life experiences is always a source of inspiration. This residency will undoubtedly open new possibilities, which I hope may take the form of future collaborations and professional relationships with Madrid and Spain.

Dreams or plans for the future?

I would like to continue exploring felt as a material, with the goal of producing a solo exhibition dedicated to this body of work. I also imagine articulating it with other practices, perhaps through a multi-media installation in the future.

I would love to return to Madrid for another artistic residency, ideally for a longer period, to deepen my relationship with the city and the people I met here, and to further expand my artistic exploration within that context.

Image 3 - Celosía, 2025

Image 8 - Exhibition View, Oneiroikos, Brotéria, 2022; Photography by: António Jorge Silva

Image 13 - Detour, 2025; Photography by: Carola Etche

Image 14 - Untitled, 2023

Image 23 + 24 + 26 - Untitled, 2021

Image 30 - Stream, 2025; Photography by: Carola Etche

Interview by Victoria Álvarez Conde. 19.01.26