STILL LIFE, BREATHING

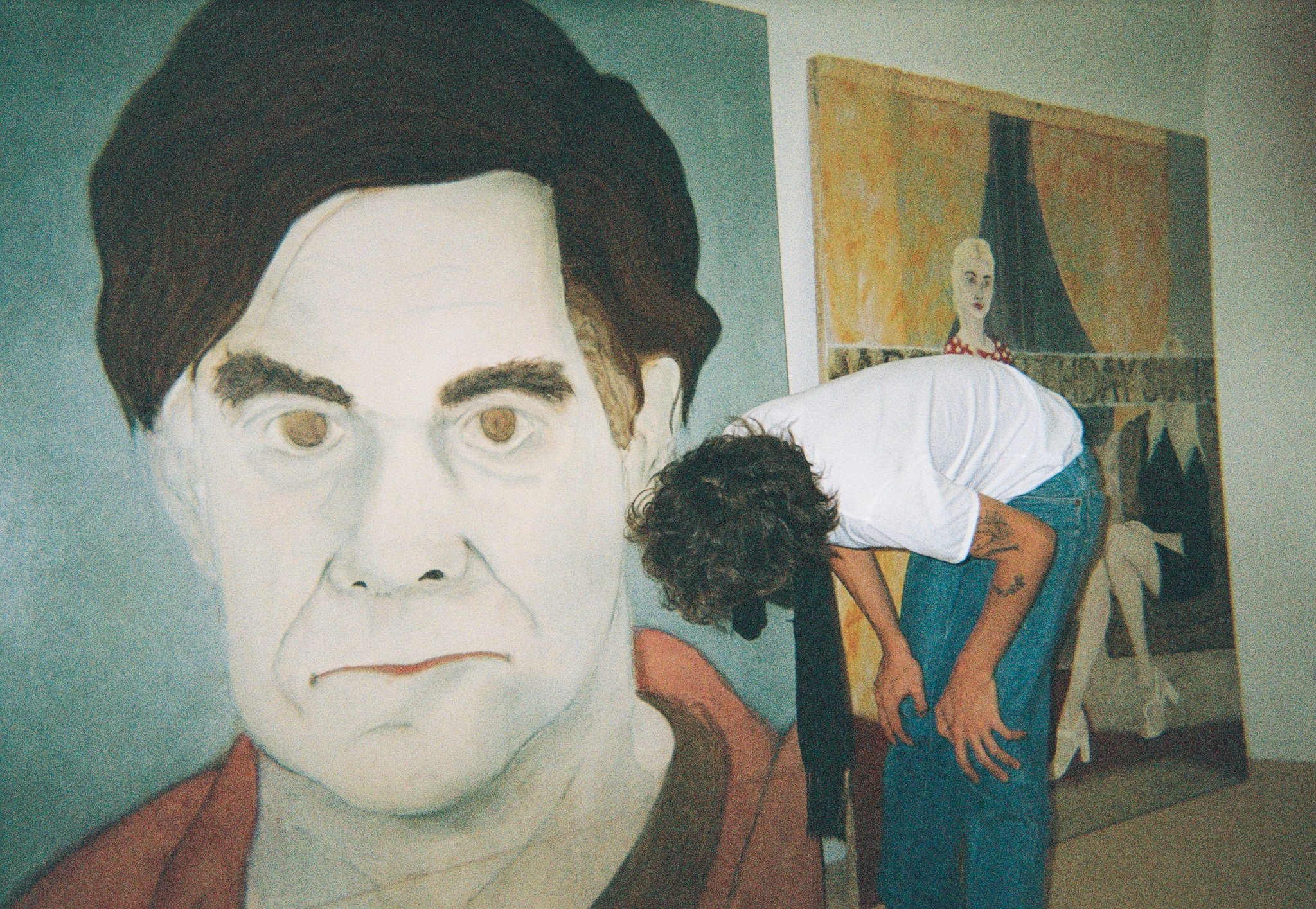

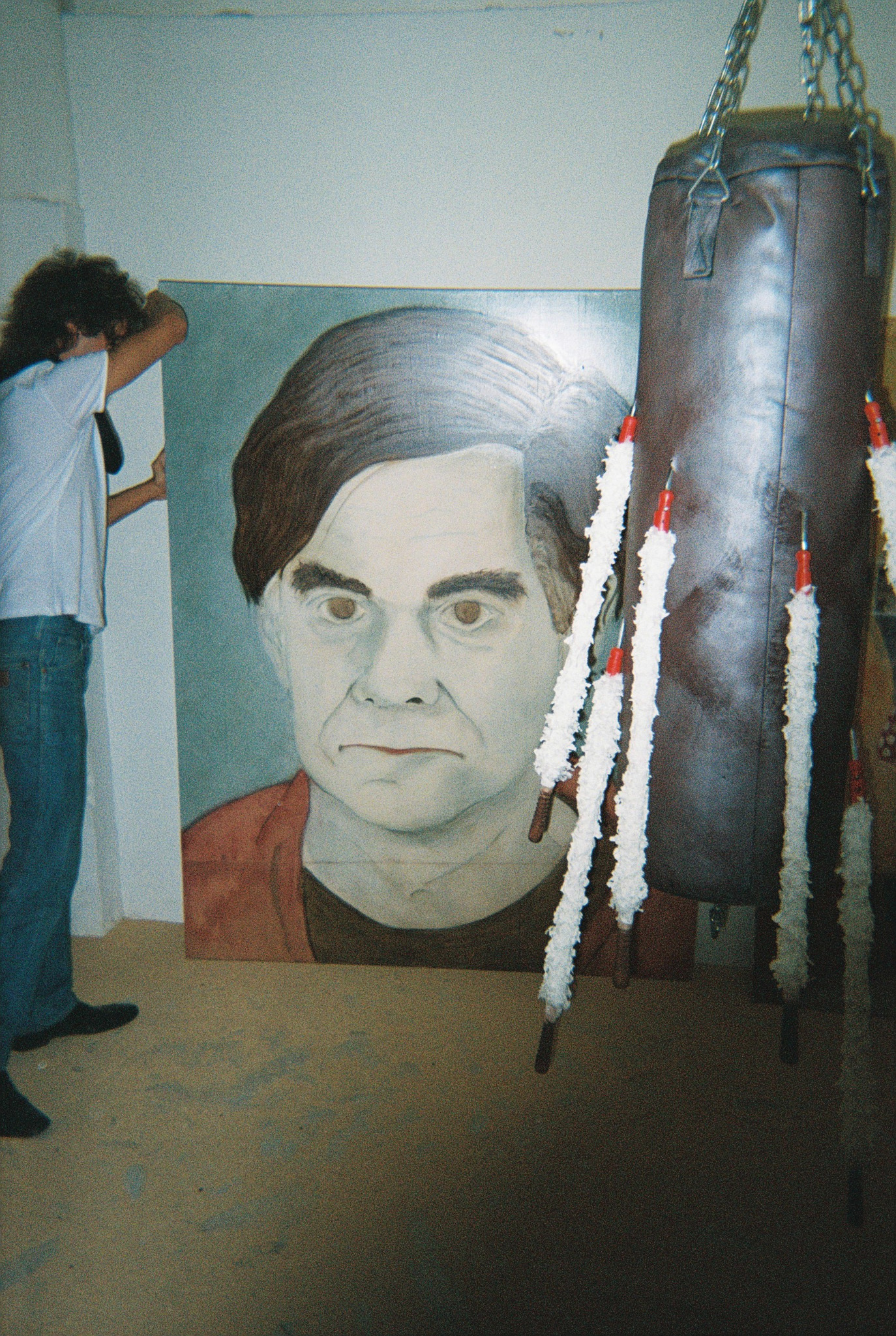

Barcelona-based painter Dahli Ball sits on the ledge of his studio’s window, over a floor still scattered with sawdust from the night before, the space resembling a narrow boxer’s pit. As we talk, we drift around the room, finally settling on the cold stone ground beneath the high ceiling, our attention fixed on one of Dahli’s pieces, “Elizabeth” — an old Victorian bed-stand adorned with a feminine figure, teetering between unsettling and provocative.

We talk about art, about middle-class suburban hysteria, about the internet as an archive of intimacy and loneliness. About the raw truths hidden within us all, whether grotesque, beautiful, or something in between. Here's to the rest of our chat:

Okay so, first things first. How did it all begin for you? Can you briefly summarize the past years of your life and how you started in the arts?

Well, I was lost for a long period of time. I didn’t know much of who I was since I had been living in a state of limbo for many years. I felt as If I was just walking around aimlessly. Entangled… I had lost my father to addiction around 2018 and was dealing with whatever was left of the fallout. I don’t know, I think it all started with the School of London.

In April this year you inaugurated the gallery Rodeo.2182. How did that project come about?

So, the idea was to shake things up. The project was co-founded by Unai Ricou, Ignasi Buneri and me with the collaboration of Julia Rodriguez, Mariona Galí and Diego Saiz. We wanted to create a space that felt different from what we were finding elsewhere. We decided to organize shows every weekend of the summer, each Friday with a different exhibition, only up for three days. If you see it, you see it. If you don’t, there’s another the following Friday. It’s cool to bring that energy back, which we know is here, but we wanted to show it more clearly, frantically and in all its chaos.

I actually love that the space is so small. It’s in these limitations that we can really see how challenges can open up possibilities. That was also part of the proposal we gave to the artists. And we’re all learning as we go along. Building everything as the weeks pass, trying to understand how it all works. It’s a bit stressful, but exciting. We’ve received a lot of support from the community, and I want to say thank you to everyone who was been a part of this beginning.

Moving on to your work… All these images have something quite quirky, a bit “off” – but also ironic. Is there a place for dark humor in your work?

It’s refreshing you ask that. Usually people tell me, “Oh, you’re voyeuristic,” or “You have a perversion…” But I think my work is broader. I like to dig into us as individuals. Our personalities, everything we hide. I’m interested in those desires that we keep entrenched in us, deep within, somewhere we don’t show. But they always end up coming out in one way or another. I think through my paintings, I want to get to that realness, that raw truth we all carry inside of us in some way. Might it be beautiful, might it not. Might it be grotesque? I don’t know.

What’s your process for starting a new piece? Does it come from a mental image?

It can. There’s this piece that comes from a girl I met when I was a kid and fell in love with—her name was Elizabeth. It was quite poignant at the time. I drew on this old Victorian bed stand, as if I were eight years old again, drawing with a pencil this portrait of the girl I had fallen in love with, in that very innocent way. But I think also it’s truthful in its own way. It felt like there was no veil, nothing complicated about it.

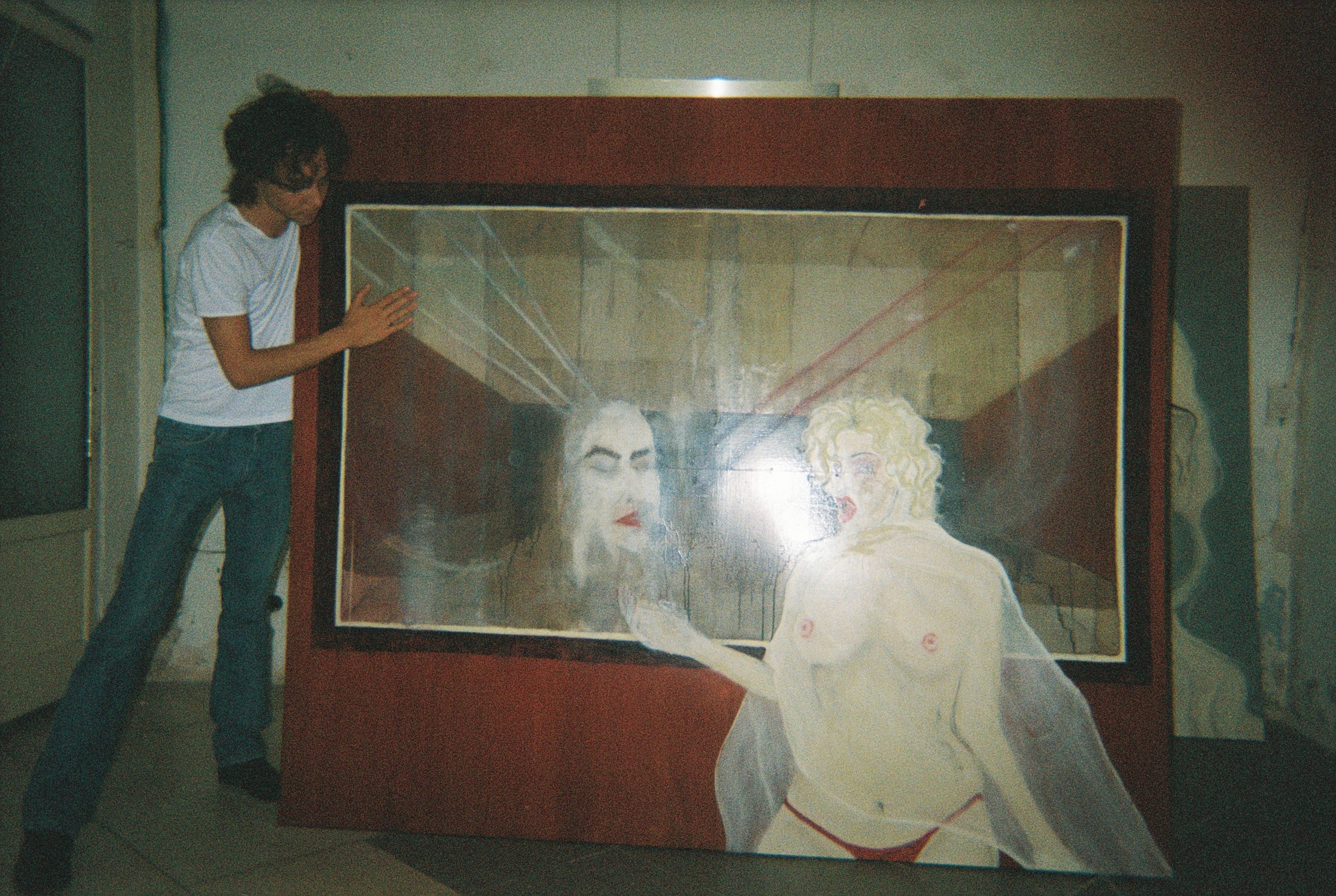

Speaking about the veil… I recently read philosopher Junichiro Tanizaki, who speaks about this element as a form of eroticism. Do you see it this way?

Yes, totally. The veil serves as this point of onlooking, of not being able to fully see what lies behind it. It’s always about the desire behind it—the possibility, the imagination. That’s why, especially in these paintings, it’s much more interesting to veil what you see, so you’re not giving everything away. You could take it back to painting—especially Guston when he talks about the enigma of finding in the work something that isn’t understood, a mystery. I don’t know. It’s about letting go.

I also noticed recurrent iconography related to dancing, nightlife and parties in your work. Where does this come from?

Yeah, that actually comes from a very personal place. When I was a kid, my mother made a documentary about a club in Los Angeles. That’s the direct reference. These dancers came to my house. I remember vividly them dancing on the pole in my bedroom, in my living room. I felt this fascination. They were just so striking. There was this power to them that I hadn’t seen before. This presence, especially the dancers, the women - they were domineering. It wasn’t that they were dancing for men; they were dancing for themselves.

In that space, especially at that time, it wasn’t just a topless party. It was a place where these women made their own choreographies, building their own art form, because a lot of them also studied dance at CalArts. That power, that possibility to give and to destroy. That’s what I see.

Because, at the end of the day, these images also come from places I’ve lived, from my past. They’re deeply personal. And in that, there’s truth. And there are things we don’t really want to see at times. I can’t always put them into words. Some things can’t be put into words.

Apart from personal experiences, who do you consider as your artistic references?

When I started painting, I was interested in John Alton and his rawness, also the School of London painters, Auerbach, Bacon, Freud, Michael Andrews, Sutherland, etc. Later I discovered Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). I fell in love with Otto Dix especially. He captured an unsettling truth about humanity—ugly, grotesque, but real. That influence is huge for me.

Also, artists like Marlene Dumas, Luc Tuymans, Jeffrey Chong Wang, etc. I mean, most of who I’ve said here are primarily painters, although much of what I do take for inspiration is from total strangers on the internet.

Artists like Dix worked in very harsh moments of history and portrayed the unrest of their whole generation. Do you feel like you too are channeling some of the general social unease of our times through your work?

Well, I always work from a very personal place but… I guess this “social” aspect can be related to my obsession with Flickr, where I get a lot of images for my work. People show very personal pieces of their life out there on the internet—family archives, images of friends, fragments of life. Sometimes with long texts explaining difficulties. I got obsessed with it. It’s raw material. Beautiful images, because a lot of them aren’t by professional photographers. They’re amateur, doing it for themselves. These candid moments tell so much more of a story.

There was this woman, Susan. She’s lying down on a bed in a black dress. I only have two photos of her left. I’ve tried to find her again online but can’t. I’m interested in her stories, in what they have to tell. She had an archive of 2,000 photos, all made by her husband. Pictures of her in long dresses. They were a couple in their 50s. Not what you’d expect. Very intimate photos, then shared in this community. I became fascinated by their relationship: how he was taking these images, how they exposed something of themselves. I love that.

I’ve begun to see these memories as a collective memory from which I pull, then build into my own. Many of these images are nostalgic: bedrooms, landscapes, things that my generation (early 2000s) have lived. They remind me of a place or time, and I repurpose them. That way, I’m reflecting something from my time and community.

In that sense, the Internet is also an archive of contemporary loneliness… Does this feeling somehow permeate your work?

Completely. A lot of these paintings are very lonely. There’s a beauty in that—a romanticisation of melancholy. They come from the loneliness I have felt myself. It’s about feeling alone in the run, at the end of the day. Like with “Liz”—it felt kind and happy, but also sad. Many of the paintings carry that sadness.

Also seeing someone die slowly in front of me left me with something I’ll never get rid of. Not necessarily bad, but it gave me a different way of looking at life. There’s beauty, but also darkness. It’s about living between the highs and the lows. Like walking a tightrope.

That reminds me of a conversation I had with a friend who is also a painter, about Apollonian or Dionysian forces. Where do you situate yourself within this scale?

In my case, it’s a mix. I’m interested in what lies behind structured middle-class happiness or stability. I feel there live all the things we don’t want to see—horrid, dark secrets, desires. I’m interested in that balance. You can’t have one without the other.

I also see something very cinematographic in your work. Are you drawn to this field?

Yes, very much. I see my paintings as scenes in transition, as stills of a moment, as a memory. A film I saw recently—Festen, a Danish film from the ’90s—I recommend it. Shot handheld, with fisheye and wide angles, it gets into very uncomfortable places. It's a very fucked up story. I'm not going to spoil it, but it touches on a lot of a what I talk about. That unsaid truth inside of us, which even when it's said, is looked over. It's a tough watch, I think, at times, but the imagery in it is stunning. I keep going back to that film.

And you’ve also made video work this year, Rosebud, right?

Yes. I had these images come back to me again and again. One of my best friend’s dragon tattoo, but in pitch-black darkness. Because he has all this hair, it looks like as if it's in a sea of black. It's beautiful because it has these popping colours. I kept getting that image. His hair looked like a sea of black. Eerie and beautiful.

Also, an image of a girl lying and staring right at me. These images kept coming back. I tried painting them, but it didn’t work. They needed movement. The only way was through video. I got the excuse through this brand, Midnight, to make a video piece. There was no product—just me losing myself, dreaming. It was a dream I dreamt over three months. Everything built around it naturally and beautifully.

In some pieces, the depiction of the body is quite sculptural and intense. Are you interested in this?

Yeah, I am interested in the body aesthetically, the messages it carries. This piece is fully oil on wood, which is how I work now. Very thin layers, similar to that of Roger Van der Waalen, or the Flemish primitives. When I saw their work in person, I fell in love with the light in the skin—the translucency.

Otto Dix worked that way too; although he started from a tempera base, building these very thin veils with the oils to create a translucency. It's very meticulous, yet quite intuitive in its own right. Building the skin from the ground up.

I love that there’s a mix of super classical painters and pop references in your work.

We have to pay homage to history, especially as painters. To negate that is to negate our practice. Those paintings still reach us because they’re transcendent, timeless. That’s what I think is important to get to. Some artists focus on making work of our time—which is important. But I want to get to something timeless.

Do you think painting can still be provocative today?

I still think it's possible, yes. But it's not something you get too easily. You really have to work and you have to paint and you have to break yourself, I think, to get to get to that.

How do you see the art scene in Barcelona?

Barcelona has a strong community, and we all support each other. There is institutional money, but only for certain work. I don’t think I really fit their demographic. There’s some movement, but it’s slow. And I don’t think it really shows the people here, what I see today, what young people or artists are experiencing. That’s why it’s important to show that there are interesting proposals, that there’s a community hungry for work, for spaces. I guess it’s part of what drove us to create Rodeo.2182.

In that sense, and to wrap things up, I was wondering - has the curatorial work at Rodeo.2182 also affected you as an artist?

Completely. It has shown me that there’s so much more I can do than what I thought.

Now I’m collaborating with another artist, and we’re making wax reliefs—small casts that we fill with wax and then remove. They’re tiny, very detailed, soft, and light. The whole process has opened up a new way of working for me.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 13.10.2025