There’s something special—and quite meta—about this interview, which took place right in the heart of what could well be a painting by the Madrid-born artist Lucía Gutiérrez Vázquez: the garden of her childhood. We are in her grandparents’ old house, a place where the artist spent many of of the summers of her youth, and to which she has decided to return this year, brush in hand, to paint live the color and texture of her memories.

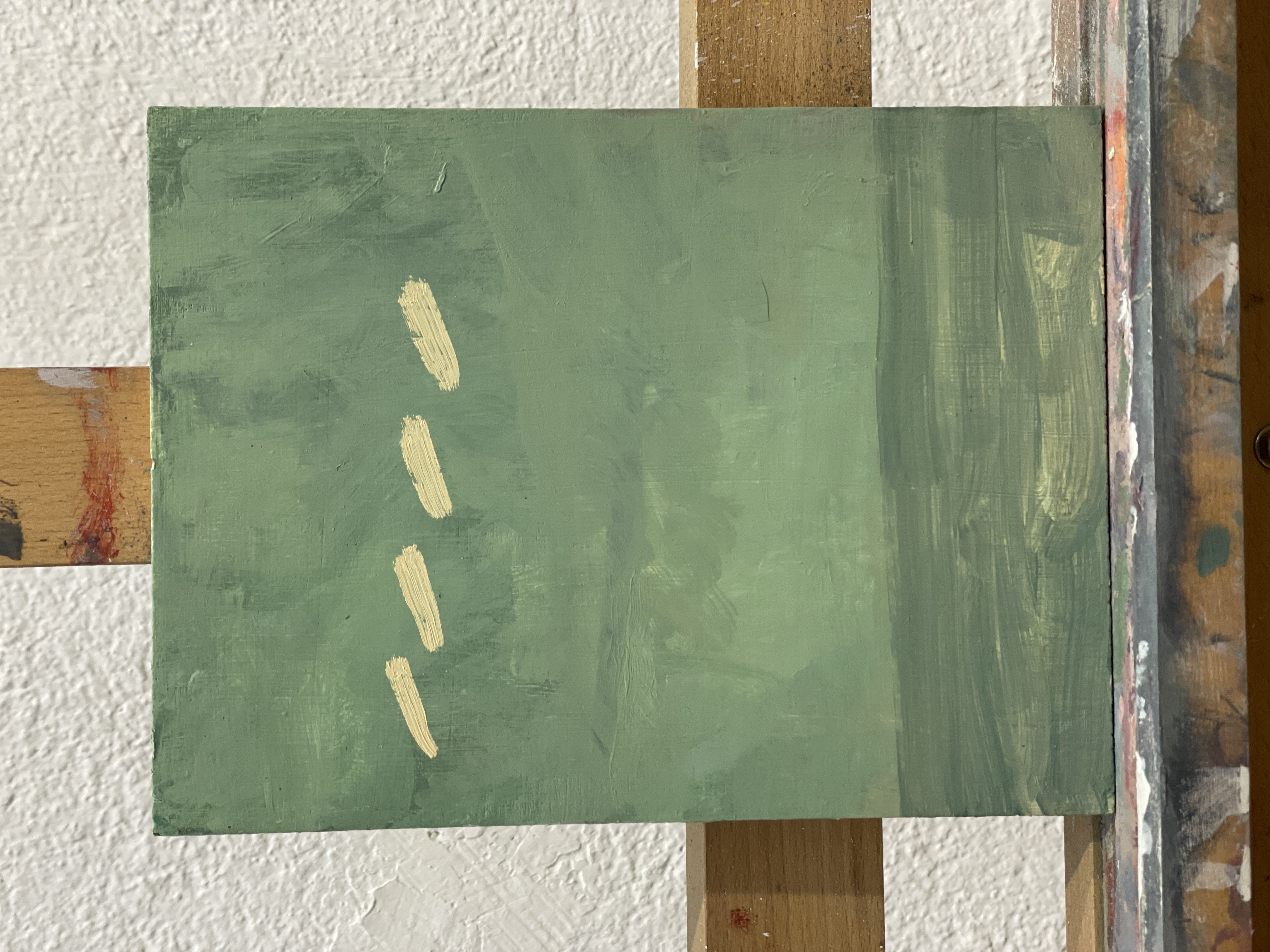

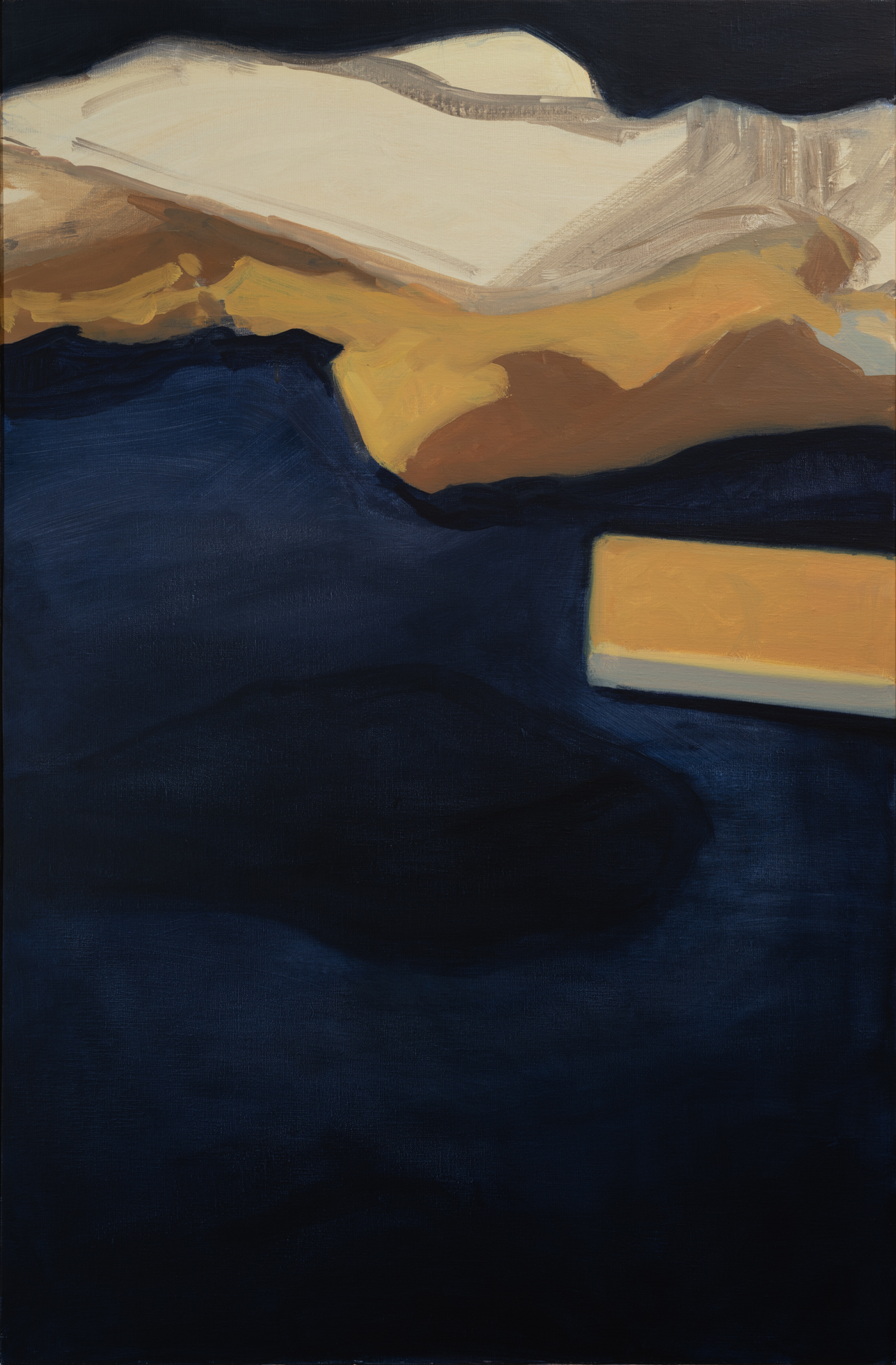

Next to the wall, the garage, the sky-blue watering cans, under the afternoon sun, the artist’s voice guides me through scenes I recognize both in the small canvases decorating the entrance and in the very landscape surrounding us. It’s an almost magical experience, like an act of sleight of hand: I see the round, blue pool, like a small pantheon, enclosed by a wrought-iron fence, and in the painting, its reflection—abstracted, transformed by Lucía into a more diffuse, poetic image. I believe there’s no better way to understand her painting than from this place, where pictorial images intertwine with colors, vitality, and, in Lucía’s own words, “the emotional connection to the subject one paints.” Her paintings, as she explains, don’t aim merely to represent an impression, but rather the personal response to it. A lyrical imprint that inhabits memory and sensitivity—a portrait of the rawness or tenderness that imbues certain scenes she captures in her work.

Lucía and I spoke about this and many other topics. All of them sunlit, musical, heartfelt, and set in an intimate, introspective space—like her work itself. Here is the trace left by our summery conversation.

Let’s start from the beginning: you studied Architecture at the Universidad Politécnica in Madrid and have just finished a PhD in the same field. Does this research relate to your painting?

The thesis is about the construction of landscape—about the concept of landscape as a tool of political power, approached from a critical perspective related to the more-than-human. It started with a critique of dualistic logic within the discipline of architecture and explored a reimagining of landscape from a less anthropocentric point of view.

I do think there are echoes in my painting, even though I find it hard to draw connections because they are very different ways of working. Painting feels very intuitive to me, not so rational. Whereas academia pushes you toward certain formats, toward a more structured way of thinking.

But there are definitely shared themes. For example, this idea of the more-than-human: in my painting, there’s a desire to connect with what I paint, which is often things that surround me—trees, mountains, vegetation, rocks… Painting becomes a mediation between the subject and me. In the end, painting is my personal vision of a landscape, understood in a very broad sense—like a bed that I paint as if it were a mountain—and that creates an ambiguity I find interesting. So yes, there’s a shared perspective, even though it comes from very different places.

As for the political aspect I mentioned, the thesis addresses it explicitly. But I also think there’s something deeply political in the act of painting slowly. Everything about painting goes against the use of space and time imposed by the capitalist world we live in. There’s something in that boldness of looking and sharing, of invoking a kind of tenderness or care for things, that feels political to me. I think that’s also part of what I do when I paint: full attention, an attempt to understand, to speak from the place where we live.

It’s touching to do this interview here, in your grandparents’ house, where you spent much of your childhood. What does it mean for you to paint here, and how does this space affect your work?

There’s something powerful about the family space, something that already feels like your own… There’s an emotional connection, a lot of affection for this house. Seeing it again moves me, and I think that emotion is exactly the starting point I need to begin painting. If I’m not emotionally moved, it doesn’t come out right.

The best paintings—well, it’s hard to say “the best”—but I think the ones that work best, the ones people like the most or that I’m most satisfied with, have to do with being in absolute attention at that moment. Being completely connected, as if thinking “I’m putting everything I have into this brushstroke.” It doesn’t even feel like it’s about me. It’s not about ego. Sometimes I go back and look at what I painted and I’m surprised, because when I paint, I enter a different state. A different temporality, an intensified space that still surprises me.

About the house... I thought being here would connect me with a feeling, a memory, a childhood experience. But that hasn’t happened as I expected. Maybe it would have happened in a different context, but not here. That was a surprise. The reality is, I realized that what I need to seek is something that moves me in the present moment. In the house as it is now, not the one I lived in 25 years ago. That’s been a learning experience. I’m glad to be here and spend time in this space, but it also gives me more freedom to understand that I can find that emotion anywhere.

That said, being here with the grapevine and the well, there’s something about this familiar place that I can come to know even more deeply through painting… I really love that that happens right here. There’s also something about paying tribute to this house. Since I’m very nostalgic, I feel a kind of vanitas of the place. As if I were thinking: “This might disappear, but before it does, I want to be present, paint it, portray it.” For me and for my memories. As a way of preserving it, of honoring it.

More broadly, beyond the works you’ve made in this house, I’d like you to tell us how a new painting begins for you: Does it start from memory, observation, emotion...?

More broadly, beyond the works you’ve made in this house, I’d like you to tell us how a new painting begins for you: Does it start from memory, observation, emotion...?Several things come together around this. On one hand, there’s something emotional that really matters to me when painting. A double sense: affection as an emotion toward what I paint, and also the idea of being affected—of being in a permeable, open state. In that sense, I felt this house gave me the chance to explore exactly that path.

In general, when I paint, it’s less about choosing a specific subject and more about following an impulse to look, to get closer. Because it’s not just visual—it’s about building a relationship with what I’m painting. It’s like highlighting key words in a text that say something more. Being able to abstract certain parts of reality, to emphasize some things over others. I’m very interested in translating that sensitivity, that emphasis.

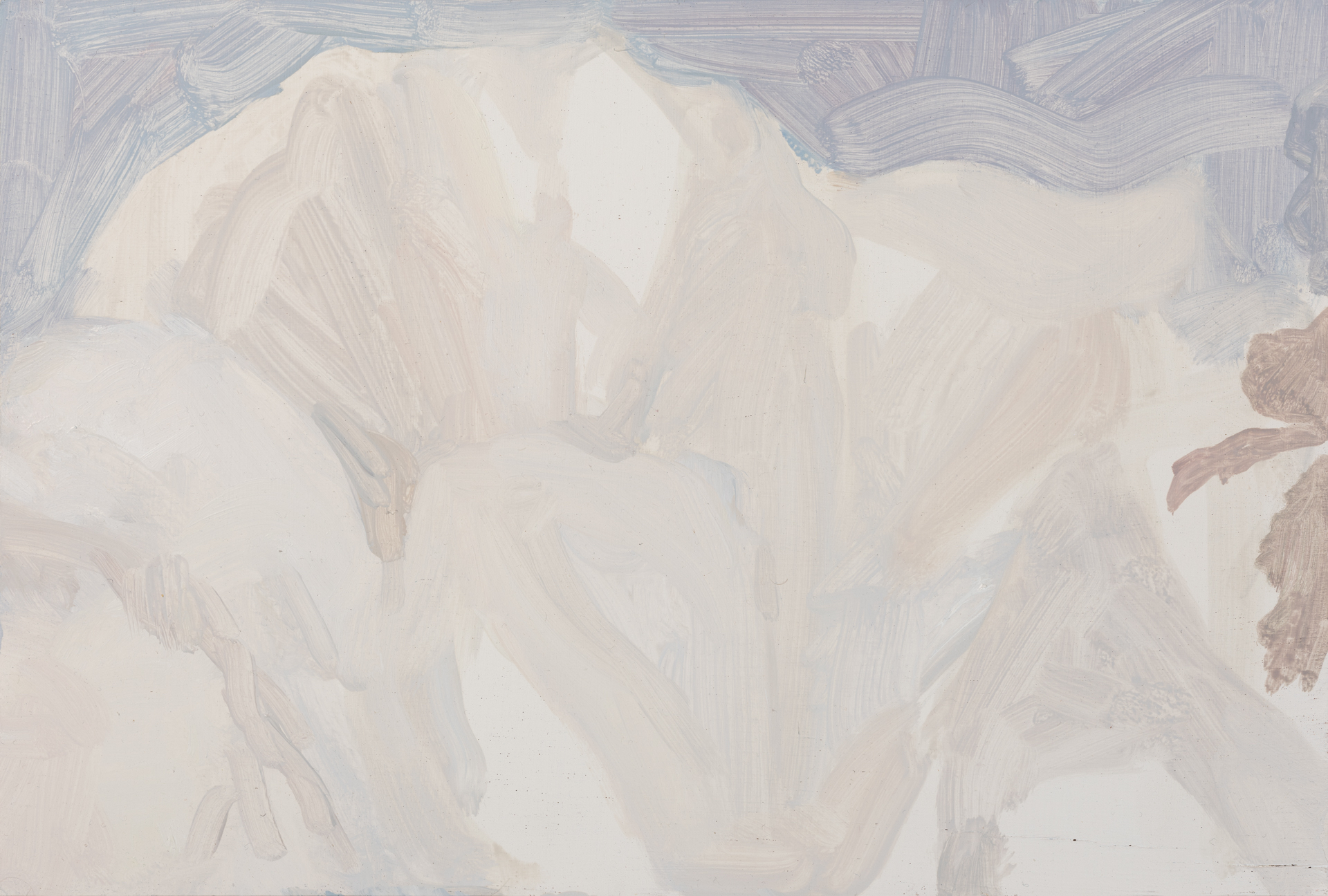

I also see the act of painting as a search. I begin without really knowing what I’m going to paint, without preconceived ideas. In that sense, I’m very drawn to oil paint—it leaves traces of the process: of looking, of searching, of doubt. It shows where you wanted to insist, to mark something forcefully… The materiality of oil even reveals the speed with which you painted—sometimes calmer, other times more energetic.

Sometimes I even surprise myself. It’s no longer something I do to communicate, but rather to understand. Often it’s frustrating, with that feeling of “this isn’t it, this isn’t what I thought I was seeing.” But even so, I feel that through painting, you also change. It’s something very alive.

There are also specific places that have been important. And this kind of obsession with certain colors. Color is fundamental in my work. In this house, for example, cerulean blue has constantly appeared in every painting. I’m amazed by how a single place offers a specific palette that keeps repeating itself. It’s not intentional—it just happens. It’s happened before: realizing later that I had used a certain color everywhere without even noticing.

Since you’ve just mentioned color—do you see it as a way of channeling emotion?

Yes, absolutely. But everything happens in a very irrational and intuitive way. That’s why some paintings are just a color stain—like that black—and suddenly it’s like: “that’s it.”

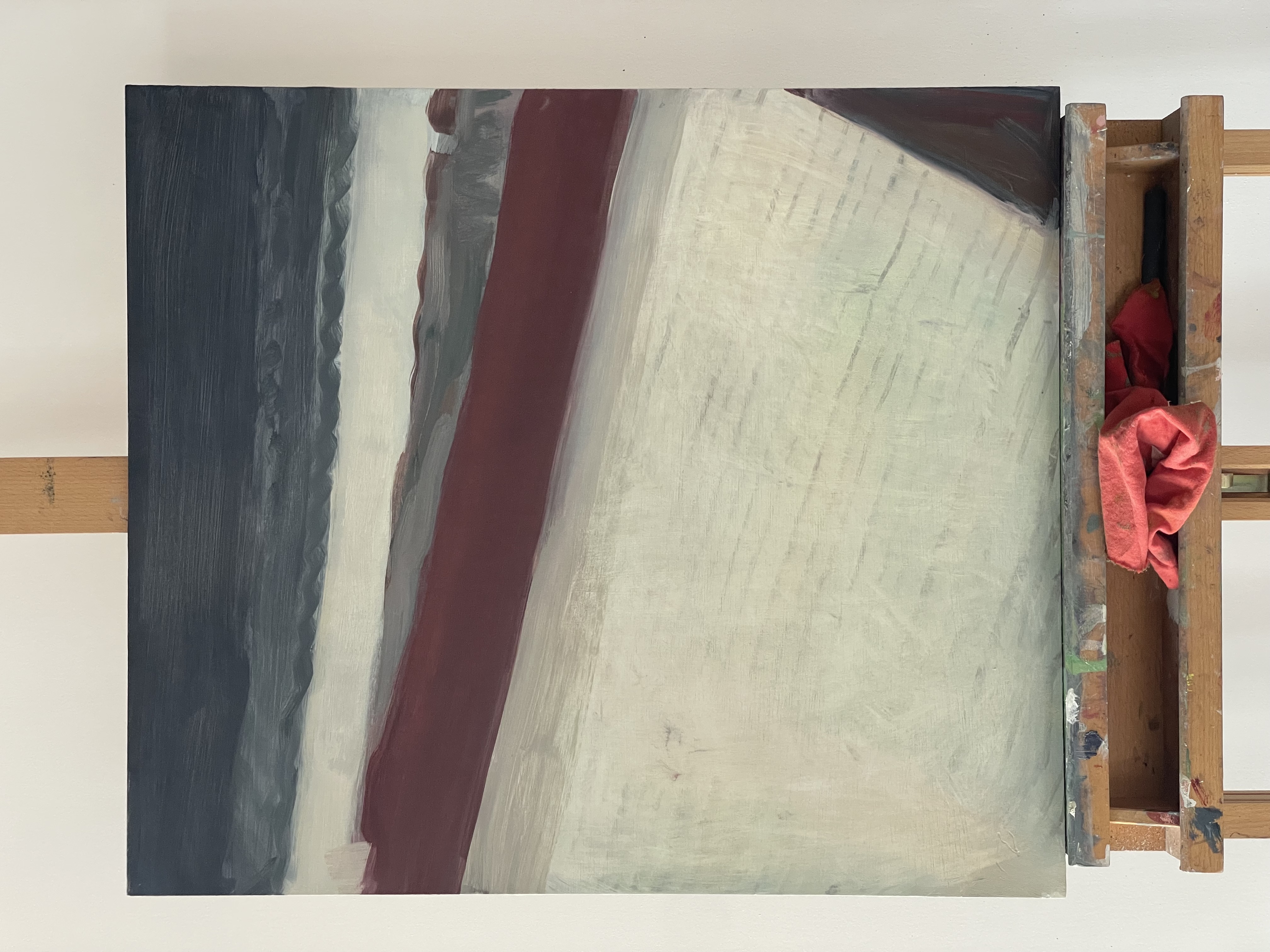

That said, I’m quite obsessed with composition. I care a lot about the effect a color has within the painting, and also its shape: whether it’s a diagonal instead of a horizontal or vertical line, for example, that changes everything.

When I work in larger formats, some colors also surround you. I’m trying to explore that relationship with scale. In small formats, sometimes the painting becomes almost an object you can treasure, and the color feels contained between your hands. But in large formats, the color expands, envelops you. And it’s not just the color—it’s also the gesture of applying it to the canvas. Honestly, it’s a very strong relationship. I find it hard to explain. At some point it stops being rational, and a poetics of color appears that I don’t quite know how to name, but that I feel is there, present.

Another thing that really stands out in your work is the way you treat interior and exterior spaces. Do you feel there's a difference between those kinds of spaces, and the themes you explore in each?

I think so, and that's actually why I’m here as well. Because in the studio, alone, I feel like something is missing. Being in contact with life, with the outdoors, with the countryside—it does me a lot of good. I like being there. Indoors, maybe I can work in a more prolonged, deliberate way. Though sometimes I also do quick one-hour sessions and that’s it. But yes, it’s a different kind of work: more elaborate, more reflective. In the studio I often work from references, from painters from the Renaissance to the present. Sometimes I set up still lifes, and other times I start from paintings I like. I really enjoy that conversation with other artists—as if the painting itself were a dialogue with their gaze.

Sometimes I’d love to paint in a house again, to return to that more intimate, more inward dimension. Lately there’s something I keep thinking about: the relationship between form and content. I’m drawn to the idea of researching intimacy or tenderness through painting. And I wonder: does that come from choosing a subject that already suggests something intimate or tender? Or can it simply arise from the way you paint, the way you approach it?

I don’t think I have a clear answer. I notice there are themes that help me access certain feelings I’m looking for, but I also feel I could paint almost anything if I approached it from a place of tenderness, if I placed the emphasis there. It’s like highlighting something, marking an intention. I don’t know… sometimes I find it hard to rationalize all of this.

And if you had to put that sensation you’re searching for into words?

Well, on one hand, I paint precisely because it’s hard to express with words. Because, really, I don’t want to put it into words. It’s complex for me, and maybe I don’t want to influence how others experience it either. But anyway… For me, there’s always a strong sense of intimacy present. As for the feeling I’m seeking… I don’t know. Sometimes I think it might be something close to calm—but not exactly. Or something I find beautiful, but in a very broad sense. Because suddenly, a plastic bar might have something that draws me in, something I can’t explain… but it’s there. Even if I can’t name it.

This is a bit different, but I also think a lot about music. In fact, recently I was asking myself: what would it look like to translate folk or popular music into painting? I feel there’s something there that interests me—a kind of place I’d like to paint from. There’s something in that—some kind of shared simplicity that attracts me. I don’t know if it’s because these are songs people sing together, or because of their very elemental structure… But that dimension speaks to me. It’s also connected to this house—something very essential, very tied to my childhood memories—without wanting to romanticize it, but with a certain truth. Like saying: “this is what I have, and that’s enough.”

Sometimes I put on music while painting because I notice it changes how I paint. Like I said earlier, the energy, the speed of a gesture—it shows in the painting. It’s very musical.

Do you have specific references you could share with us?

Richard Diebenkorn, Georgia O’Keeffe… Lately I’m really into Howard Hodgkin. Among 20th-century painters, also Milton Avery, Joan Mitchell. And Morandi—I sometimes forget about him, and then when I come back, it’s like: whoa.

Also, since I went to Florence a couple of years ago—well, really even before that—I’ve been very interested in Italian Renaissance and pre-Renaissance painting: Masaccio, Giotto, Piero della Francesca… That kind of gaze, that way of constructing.

We’ve also talked about that blend of figuration and abstraction in your work. Could you tell us how you position yourself in relation to that, and what leads you to one form or the other?

I position myself in wanting it not to be a dichotomy. I find it a simplistic division—almost outdated. For the catalogue of my last exhibition, Antonio Muñoz Molina wrote a text with a phrase I love: “there is no vision that is not abstract.” I think it’s beautiful, and very true. Even in painting that’s considered highly figurative, if you look closely at a detail, it’s pure abstraction. And the other way around—there are things that seem abstract but are actually based on something very concrete, a real model.

I like avoiding that distinction, even if it’s sometimes difficult. I don’t want to stick to any particular label. Sometimes, within the same exhibition, there’s very little difference between the paintings—but other times there are pieces where what I’m painting is perfectly recognizable, and others where it isn’t. What interests me is exactly that: mixing, blurring the lines, letting different forms of representation coexist in a single painting. I think it has to do with where I place the emphasis. Sometimes a blotch of color is enough; other times I need something more defined. That coexistence works for me. I like it when painting enters that zone of ambiguity.

I’m also interested in breaking away from traditional genre categories. For example, painting a flower, but on a different scale—so it feels like a landscape. Or bedsheets that, through the abstraction of paint, become a mountain. Maybe it’s still figurative, but it’s gone through a set of processes that change it. It’s in that hybrid zone that I feel most comfortable, where I think both things are at play. That’s why I find it hard to separate them.

Okay, here comes a deep one—just a heads up. Many painters say that painting connects them with a kind of transcendence, something beyond themselves. Do you share that feeling?

Yes, absolutely. Transcendence, but more connected to the present moment—not in the sense of “my painting will live on.” It’s something else…

I recently read about the concept of flow—I’m not sure if that’s exactly it—but it’s like when you’re no longer in control of your gestures; the body enters a kind of connection that moves faster than the mind. There’s no conscious intention—just intuition and energy. It’s like you’re seeing something and, at the same time, expressing it as if you were a channel. That sensation defies any attempt at control.

I don’t want to make it sound too mystical, because it’s not really that—it’s just something you can’t force. That’s why I think it holds a kind of truth. The best brushstrokes—I don’t even know why I made them; they just come out quickly, with an inner certainty. It’s like when you’re doing sports or dancing and you’re fully focused on one part of the body, fully in the present. That sensation is incredible, though sometimes it can also be very tough. The vulnerability of giving your all, of pouring all your emotion into each brushstroke. That’s what feels transcendent to me.

I’d love for you to tell us how it feels to bring these very intimate pieces of yours into an exhibition space.

It’s been pretty intense. Last year I had a solo show at Galerie Mercier in Paris that I had been preparing for several years. Starting in 2021, I began painting more and more. In the summer of 2023 I went with my partner to Val de la Sabina, a village in El Rincón de Ademuz, to paint there. It was a really important experience.

From that period, I brought 60 paintings to the gallerist in Paris—an enormous amount. It was amazing to see them all together because it allowed me to better understand myself. The truth is, I’m still searching, I’m still in the process, and I’m aware that these last years have been about finding a language—almost a personal pictorial language—putting myself in conversation with the entire history of art and painting. When I saw them all laid out on the gallery floor, suddenly it was like: wow. It gained new meaning, new interpretations.

Also, the process of composing the show—deciding which paintings are paired together, what the path through the show is like, how it’s seen by the person walking with you—that’s something I find really beautiful. I really enjoy the relationship with the gallerist too: that moment when we share our impressions and figure out what works best. I’m also very interested in the architectural dimension of placing the work in space—it’s huge. Even deciding the height at which a painting hangs: it hits you differently. It’s fascinating.

Then there’s the commercial side, which inevitably comes with exhibiting. I think I try to keep that a bit separate. Of course, I want to sell, because that’s what allows me to keep doing this, but I try not to let that overshadow everything else. I don’t want to worry more about whether something will sell than about what I’m trying to say. And having a gallery to work with is amazing in that sense too, because I don’t have to worry about selling—it’s not my role. My job is to focus on what I’ve painted. Honestly, it’s been a year of intense work—it’s been exhausting, but also really beautiful.

I know you're currently doing a residency at C-Factoría, where you presented a project about scale in painting. Can you tell us a bit more about that topic?

What I proposed for the residency at C-Factoría was to explore the relationship between scale in painting and intimacy. In painting, there are many decisions to make regarding scale: from the size of the format you choose to the size at which you depict a figure within that format. That decision —to make it bigger or smaller— completely changes how it's received, and also how it’s painted. There’s also the relationship with the model, if you're working from life: the distance, the proportion... And then, the relationship established between the painting and the viewer —or even with myself.

For example, I’m fascinated by how a gesture that you can resolve in a small format with just a brush and a minimal movement, when taken to a large scale, becomes something physical, almost choreographic.

Another aspect of this research that really interests me has to do with the material side of things. Lately I keep asking myself: if I want to take something I know how to control on a small scale and bring it to a larger format —and see whether it becomes more immersive rather than more intimate or contained— how do my tools need to change?

There’s a quote I really love by Georgia O’Keeffe. When asked why she painted flowers so large, she answered: “No one asks me why I paint the river so small.” I find that implied convention around scale really interesting: what is expected to be large or small, especially in relation to landscapes or objects. I'm interested in rethinking and breaking those conventions.

Another reference that really inspires me comes from The Book of Art by Cennino Cennini, where he mentions that one way of painting a mountainous landscape is to place stones or rocks on a table and paint them as if they were a landscape. I find it such a conceptual and intuitive way of understanding the shift in scale, and I love thinking from that place. In fact, the project I proposed is called “To Paint a Petal as if it Were a Mountain.”

On a related note, in a recent conversation with another artist, an idea came up that I found fascinating: that poetry, although it sometimes feels imprecise, is actually the opposite... it’s incredibly precise in its apparent imprecision. As we spoke and looked at your paintings, I wondered: do you see that poetic way of saying —a kind of indefinite definition— in your own practice?

Yes, absolutely. Poetry does amazing things with language. It's able to convey an emotion, a vision, a perspective that no one else has expressed in quite that way, and it's like: “Yes, that’s it.” That’s how I understand painting. Often —frustratingly— because it doesn’t always come through, and I think: “No, this isn’t what I meant.” But when it does happen… it’s something beyond what you could have planned. Something that escapes you, that you can't fully control, and that expresses more than you could have said yourself.

There’s a book called The Art of Lighting Words, by Berta García Faet. It’s more of an essay on writing and poetry, but when I read it, I kept mentally translating her ideas into painting. In it, Berta writes:

“I say that each poetic saying says a —its— truth. I say that Emily Dickinson says: ‘tell all the truth but tell it slant.’ I say that the poetry that moves me seeks to convey a —its— intimate conviction: the rawness or the tenderness of a singular existence.”

That last sentence is exactly how I understand painting.

Quoting another author —just yesterday, we were talking about Mary Oliver— there’s a poem where she writes something like: “Instructions for living a life.” It says: “Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.” That connects deeply with how I see painting: paying attention, being fully present, open, porous, affected... letting yourself be surprised. And telling about it.

And, sadly... Let’s go with the last question. Any future dreams, projects, or plans?

Right now, I’m very drawn to large formats. They intimidate me, of course. I don’t want to abandon the smaller pieces I’ve been making —which I also love— but now that I have the space, I really want to explore large-scale work and learn from it.

Just yesterday I felt like some sort of alchemist: “More oil, more turpentine... This jar doesn’t work... I’ve run out of color... This palette knife...” Basically, throwing myself into that deeply artisanal side of the process. That’s exactly where I’m at right now, and what I want to keep learning —just like when I first started mixing colors on a palette.

As for dreams, I’d love for one of those large paintings to really work. It’s hard to explain, but sometimes you just know when a painting “works.” It feels finished, evident.

I’d also love to collaborate with other artists. Not necessarily painters. One of my best friends is a playwright, and we always talk about doing something together. I don’t know yet what shape it would take, or in what format, but I feel the desire to learn from other people, to blend things together.

And —hopefully— to keep making a living from this, which is also important. I’d like to do more exhibitions. And since we’re dreaming… well, I hope things go well [laughs]. That people keep being interested, that the work continues to resonate... And that I stay excited about it. Above all, that: to keep painting with intensity and consistency.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 30.07.2025