Once upon a time there was a pencil and an artist, who at thirteen sold all her manga comics to devote herself to digging through her family’s photo albums: the bookseller, the circus contortionist, the anarchist’s son, the one who worked in cinema, the one who owned a horse… Stories, memories, and characters that reappear in her delicate small and large-format paintings, stacked like piles of books in her studio in Zona Franca.

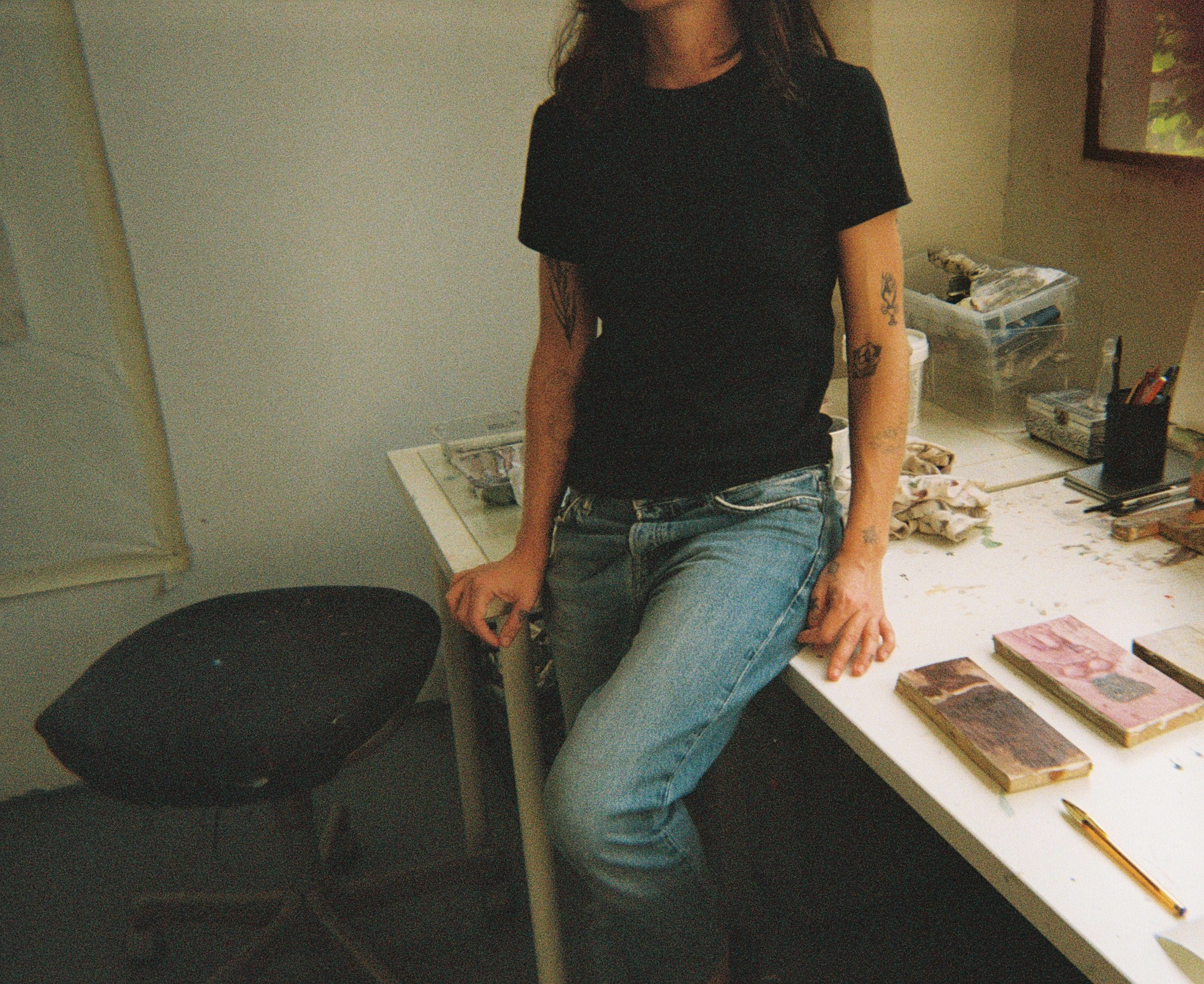

Inside, Iris unfolds the works before my eyes, like someone turning the pages of a diary. The first time I saw her work was in the hands of a common friend who had bought a tiny rectangle of wood decorated with a somewhat schematic face of a sleeping woman, almost a childlike drawing in pastel tones. Since then, the artist has exhibited her work internationally, in cities such as London, Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, and Palma de Mallorca. Now, back in Barcelona, the artist rolls one cigarette after another, enigmatic and tattooed, smoking while we talk about childhood and sexuality, about walks and daydreams. Also about fantasy and children’s literature, diaries and memory, and about that slightly naïve quality in her painting that, according to her, allows her to remain somewhat ambiguous: not tied to a fixed or easy message, nor married to anything, or anyone.

You were resident at Casa Antillón in Madrid two years ago, and lately you’ve been part of several group exhibitions here in Barcelona. Before that, how did it all begin? Could you tell us about your whereabouts over the past few years?

I imagine it’s the same story we painters usually share. As a child I drew, right? Yes, the best is to start like that: as a child I drew.

My grandmother was a painter, though not professionally. Painting was very present in my childhood, because I spent a lot of time with her as a girl. She invented creative games, took me to museums, and had a big library which included some art books. That’s where everything began to awaken. Later, around six or seven years old, when most of us stop drawing, I discovered manga.

I started making comics, but something always happened to me that, over time, I’ve come to understand: while I started them, I never continued them. I could only do the cover. I made the cover, maybe the first page… but I didn’t follow through with the story. In a way, I was already making paintings. A single image, a fixed scene. If I wanted to tell a story, I wrote it. Repeating the same character, giving continuity to the drawing, bored me enormously.

Afterwards I chose art in high school and ended up studying children’s illustration and self-publishing. It’s something very specific, with that naïve quality—in the sense of being free—that I enjoy a lot. It allowed me to go along with things that aren’t so closed, that perhaps have a discourse, but on another plane, in a less direct way.

Children’s illustration begins from stories, from fables… We worked with good texts, some with a powerful background. As children we recognize part of that content, and when we reread them as adults, they take on another dimension. Rediscovering that door really encouraged me. Even so, I quickly noticed I returned to that childhood feeling with comics; that I was limited by the format.

So I went to Escola Massana, where I studied Applied Arts. Painting, ceramics, sculpture… even performance, haha. Right now I’m in my second year of Philosophy, though that’s another story.

In your work, characters and symbols that are typically feminine appear repeatedly. I’m struck by the fact that (and now that you mention your background in children’s illustration it surprises me less) it’s a world somewhere between childhood and adolescence. What attracts you to that imagery, or where do these images come from?

I understand they’ve always been there, from my memories… It’s more a reading people make of my work, not so much something I deliberately pursue, but it fits me quite well. Everything has a somewhat autobiographical point, which I think happens to people who create. No matter what you do, I believe what you add or omit has to do with your daily life, your concerns, and your convictions. In my work, it’s not so much that I say “I want to represent this,” but that these are traces that have been accumulating… and suddenly resurface.

It’s likely that what I write, what I draw… all that mix refers largely to two things. The first would be childhood, understood in a somewhat romanticized sense, a little in the style of Wordsworth. I don’t know if I like entering it that much, but I have to admit I’m moved by the existence of a time lived with natural sharpness and lack of prejudice—closer to truth, so to speak. It’s as if the memory of having truly played, and the possibility of playing again in the present or future, could bring light into our adult life.

In fact, my residency at Casa Antillón ended up revolving around that. What was initially going to be a medieval bestiary reinterpreted in a contemporary key ended up being a proposal about childhood memories, about how these are transformed within us. You have the memory of the experience, but it changes and reshapes itself. It gets infused with what you live afterward, you feed it with other experiences.

Secondly, I’d point to the importance of the moments I spend alone. From there derives the relationship with the feminine, with intimacy. Walks, the home, swimming in the pool, my obsessions… those kinds of things.

Strange things happen on walks. One of them is that they involve the body and thought in a peculiar way. At first, walking is a rather monotonous gesture, quite neutral, so to speak, but not completely passive. I think you think differently when you’re in motion, especially when that motion is automatic. Then comes the sensation that the mind adjusts to that rhythm, that it too walks. And on top of that, you can come across surprising interactions. The factor of surprise inspires me a lot. When you walk aimlessly, things happen that you don’t expect because you’re not going anywhere in particular, there’s no plan, you don’t have to meet anyone. Anything could happen.

Although my interest is rooted in the relationships we establish with our environment and the people around us—because I suppose that’s what it’s all about—those moments alone help me sort out my ideas. They help me gain distance, to understand how those bonds operate. For me it’s vital to represent how that space unfolds, while also procuring it for myself. Also, growing up as an only child, you get used to making up stories in your room and later find it hard to let go of that.

There’s also a very family-based part in my work. The different professions of my grandparents: the bookseller, the circus contortionist, the son of the anarchist, the one who worked in cinema… All captured in family photo albums. I often ask my family to send me pictures. For example, that painting over there…

[Iris points to an unfinished painting depicting a splendid woman standing on a man, at the beach, both in swimsuits.]

The girl in the center comes from a photo of my grandmother when she was about 12. She’s standing on my great-grandfather, although in the painting she looks nothing like herself. It’s another person, in another pose, with different background characters. But there’s something there about preserving memory and being able to return to it. Also something of remaking it, I suppose.

Other times, ideas come right before I fall asleep. In those moments, sequences of images and a certain narrative emerge—and those can become paintings. I guess those are moments when memory is at work.

Within that feminine imagery we’re talking about, there are also explicit references to sexuality and masturbation, in scenes that often produce a certain tension. What are you trying to explore through these kinds of images?

Desire and sexuality are very present in my work, even when I paint landscapes or anything else. For me, painting is something very sensual, very much of the flesh. In this studio I can paint comfortably because I have a good relationship with those around me, but, honestly, when someone comes in to visit, I immediately stop painting. Because it feels like a very private exercise, almost masturbatory. A dialogue with myself, sweeter or harsher depending on the day.

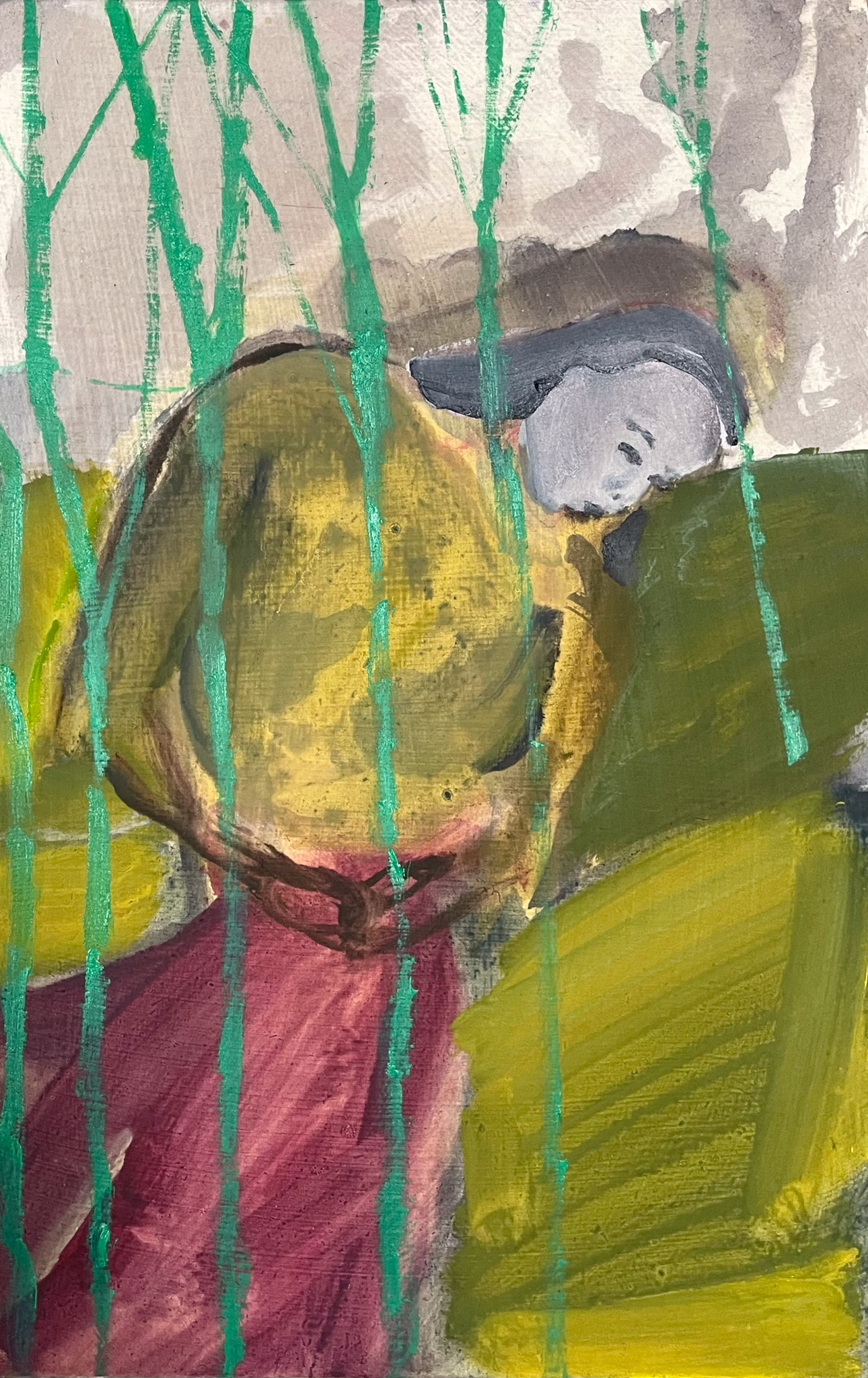

As for desire, I think it’s always present in my life—how it works, how it moves us, where we direct it… And, more specifically, I’m interested in the power dynamics that occur within sexuality. While this might appear in my work, I try not to make it too explicit. In fact, I think I always use a soft palette and a rather gentle type of drawing, so that a scene that could be very raw is softened and sits in a more ambiguous place.

For example, the painting of the girl lifting her dress. Even I don’t know exactly where that painting came from. It started as a joke, like when you’re with a friend and you pee in the street—that moment of complicity. Then I didn’t know whether I was painting a scene of exhibitionism between strangers, or what.

But that’s it: what could be rougher, more literal, suddenly, when you put a certain expression, a certain use of color, it gets toned down and lands in a liminal space. That interests me, treating desire in a more organic way, even if we’re talking about traumatic or painful memories. In that sense, it can actually be a positive task for me. A process—not of romanticizing—but of giving it another look, of regaining agency and being able to speak about it.

Along those lines, your work has a somewhat dreamlike tone, between wake and sleep, as if situated in a territory of fragmented memory. Are you specifically drawn to the world of dreams?

I guess I am, but without wanting to make it too explicit. In figuration it’s very easy to tend to represent scenes in a very clear way, and without wanting to criticize that, in my case, I feel that images that aren’t fully understandable help me. That’s why I blur everything. The fact that my work fits into an undefined, dreamlike language and style allows me not to box myself in and to mutate ideas constantly. And me, since I don’t tie myself to anythingm or anyone, that suits me.

In the end, it’s a process of: “Okay, I make this image, I erase it, maybe another one appears, I erase it again, and from that something emerges that’s not entirely clear.” It’s more a matter of erasing, leaving only the minimum visible and the most open possible. I use sandpaper, erasers, layers and glazes, but not in the traditional sense of oil painting—layer upon layer to preserve them—but the opposite. Behind that work there’s time, hours, but you’d probably only see it with X-rays. There isn’t that mass, that containment.

I deeply admire my painter colleagues who are patient people, who stick to one idea. In my case, it’s more: “Okay, this is here, but what if we let it become something else entirely?” I always let things rest, even if I paint fast, just to look at the canvas, smoke, and wonder whether it can become something completely different, or if I need to erase it and see in that erasure what remains and what might appear.

Large pieces can give rise to very different interpretations, and I find them all equally valid, because even I don’t have a fixed interpretation of what I do. Most of the time I have no clue, basically.

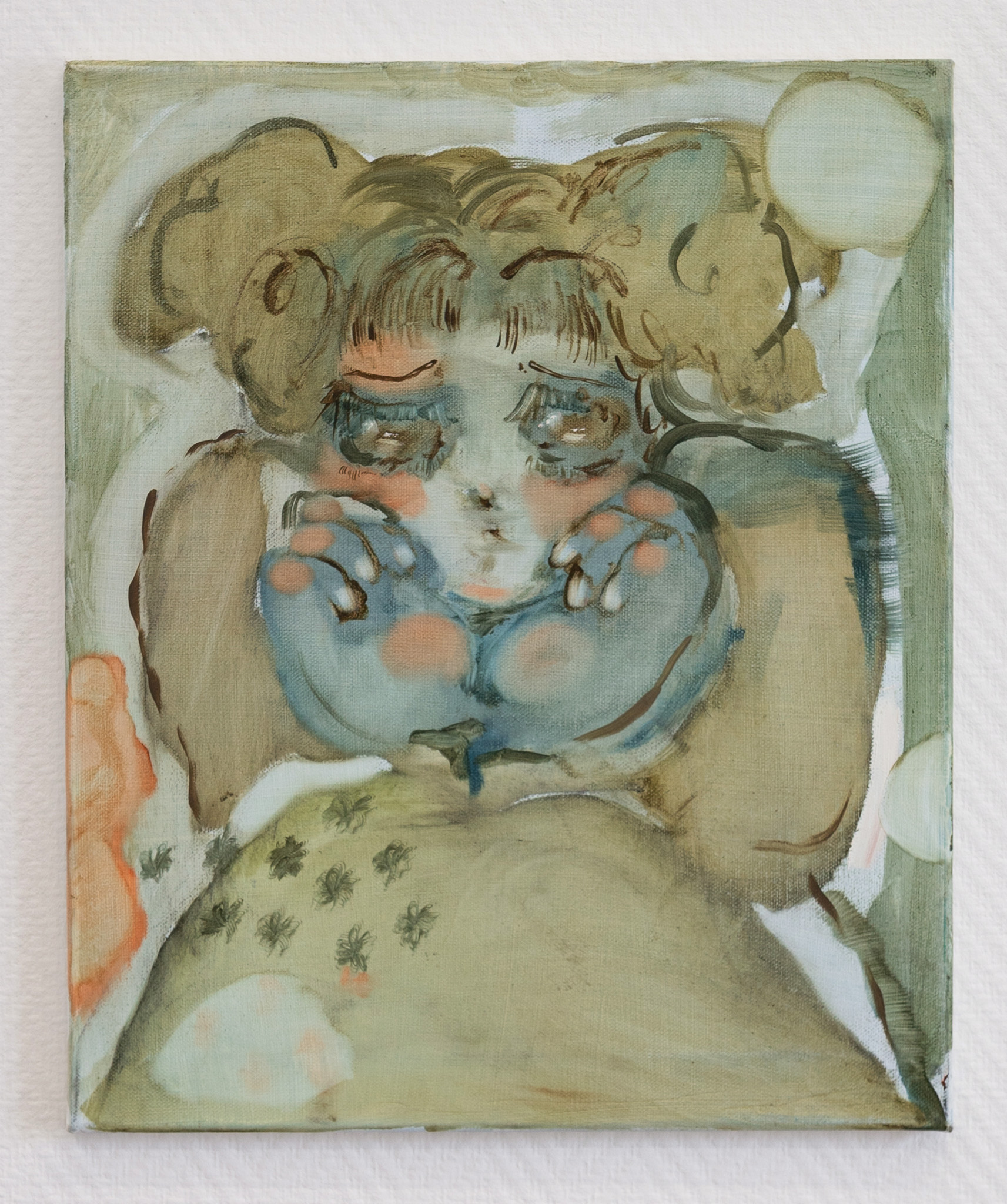

You’ve also mentioned your interest in manga, and I wanted to ask about that influence, which even today is very noticeable in the faces that appear in your works. Are you interested in keeping that trace of your past noticeable in your work?

It’s there, yes, and I quite enjoy it. As a kid, between six and eleven years old, I had already gathered a large comic collection at home. I always consumed it a lot. People from my generation went through something similar. Though in class, along with a couple of friends, we were the “manga nerds.” We went to conventions, dressed up, did all that. Then suddenly, I distanced myself completely from it.

Years later, it suddenly resurfaced in my drawing, whether I looked for it or not. At times I used it more as a stylistic resource. Maybe now I’m not so much in that line, but some of it remains. It comes out unconsciously. When I draw without thinking too much, I don’t do an academic face, it just comes out with that little touch. And I love that, that things from that time remain in me.

Are there other references that you recognize in your work?

Of course, I’m aware that whenever someone creates, they’re reappropriating something, beyond their intentions.

A friend recently asked me what had inspired me, in my teenage years, to paint and make things like this. He had it pretty clear for himself. Honestly, I froze. I told him that as a kid I wanted to be a vagabond, and that’s true. I don’t know, the list of things is endless… I suppose, to a greater or lesser degree, it’s everything.

As for painting, I have small obsessions that vary. Right now, more contemporary ones, and working in figuration, to narrow it down… well, I love Marlène Dumas, the work of Luc Tuymans, Mamma Andersson, Ambera Wellmann, Peter Doig, Tracey Emin… But also sweeter things, like Milton Avery or Alex Katz. But you already know them, I don’t want to make this a succession of names—or worse, leave out important ones and regret it later.

All that said, I try not to look at them too much, otherwise you end up falling into the obvious. I prefer literature, photography or film if I want to gain momentum. Right now I’m reading The Waves by Virginia Woolf, and not long ago I really enjoyed The Man of Jasmine by Unica Zürn. Those were the two summer readings that impacted me most, recommended by a good friend. I’m sure paintings will come out of that, or a poem. At the same time I read a lot of essays, philosophy… From that I get arguments, I restructure myself, I steady myself a bit. I suppose that’s also a way to get inspired and exercise the ability to discard.

And, of course, chatting and seeing the work of artists around me, who are excellent. In Barcelona there are many people doing amazing work.

You’ve written about the relationship between the intimate and the mythical, as well as referring to the medieval bestiary you proposed for the Casa Antillón residency. In your work, how do you explore that connection between the everyday and the fantastic?

A few years ago, I probably understood that fantastical spectrum in a more literal way. I leaned toward symbolism and mysticism, incorporating it into my paintings. I drew creatures, half human, half animal. Then, little by little, it’s not that I’ve let go of that magic, but rather that I’ve grounded it much more in the everyday. There it found its object.

My interests in that respect have settled more on things I encounter in my daily life, the things I touch. Above all, in the bonds between people, as I mentioned before, but also with other beings, like this fantastic tree we have here…

[Iris points out the window to a beautiful tree of love, swaying gently in the breeze.]

The figure of the horse, an animal with strong symbolism, recurrently appears in your work. Does it have any specific meaning for you? What do you seek to convey with this image?

I think that also has to do with my family, with my childhood summers. My grandfather had a horse when I was little. I don’t remember it that much, but there are tons of photos of this animal in his house. So I imagine in that act of recovery, the horse is always present.

There’s also that general connection between painting and horses. Honestly, I don’t think there’s any animal more pleasurable to paint: all those volumes, everything it represents, its strength. Besides, I often paint female figures in dialogue with the horse, bringing it into subtlety, taking it out of the typical image of the monarch on horseback. But, well, nothing that hasn’t already been done thousands of times.

For me, horses are very tender animals. My cousin works with them. I try to visit her from time to time at the stables, though I guess they’re not really that well there. I love seeing them fall, how all that strength is released. They’re actually quite naïve animals at heart, though it may not seem so. Watching them fall is incredible, just like seeing them trot. There’s a special release in their hair, their gestures, and their interactions that I like to bring into my own terrain. But in the end, above all, painting horses is just an incredible pleasure.

In general, nature is very present in your paintings. Is there an intention to bring those forms to life in your work?

Probably yes. It’s not that I give them life, it’s that they already have it for me. In this case, I think it’s also tied to longing. I live in the city, in central Barcelona. Even so, I interact a lot with… well, luckily we still have trees on the streets! That gives me a breather and is something I’d like to have more of around me.

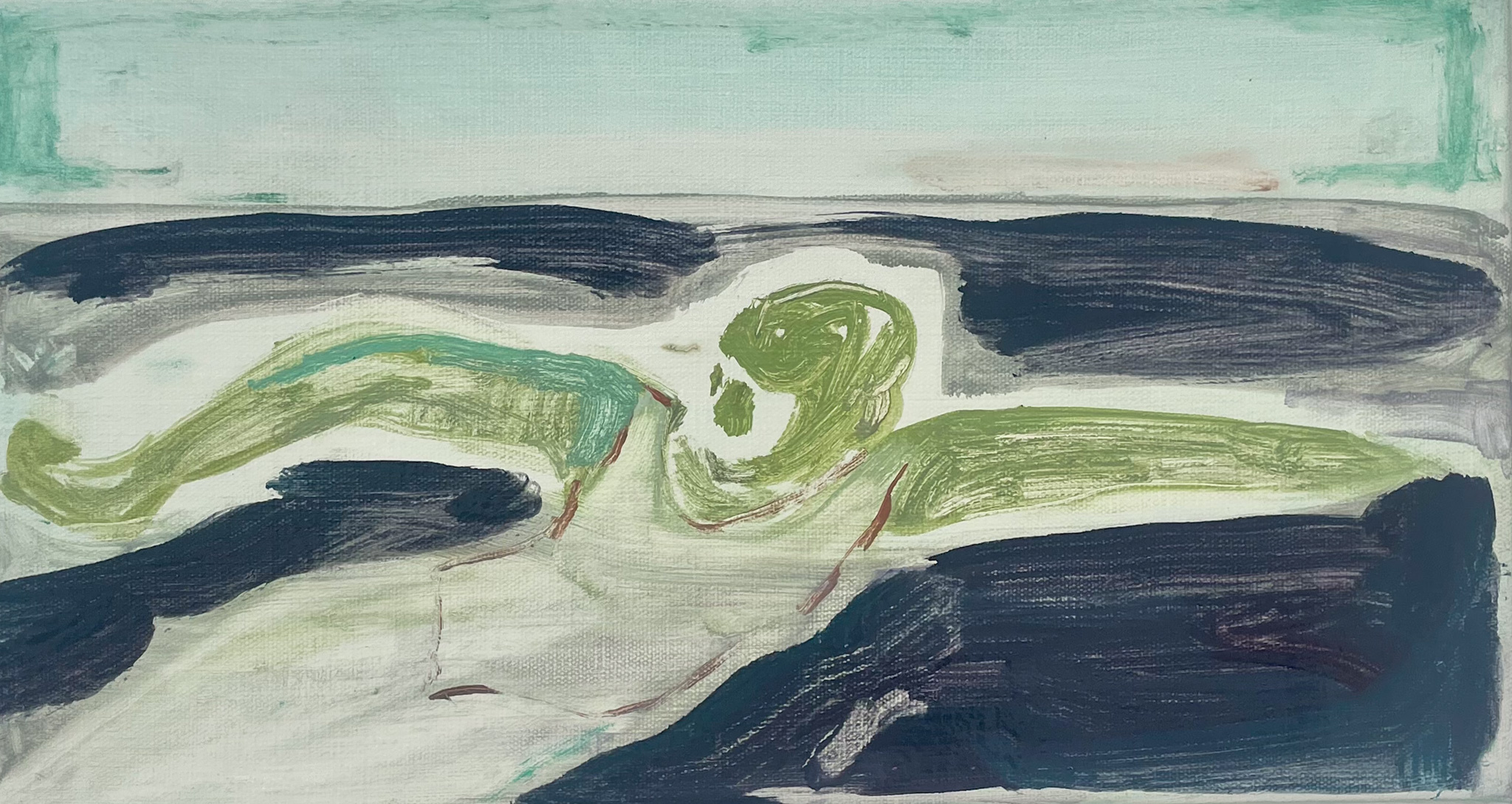

Giving them life—I don’t know. They have the same sympathy or antipathy, character, or whatever, as any character I might paint. For me it’s not that different from painting a human body. This painting here, for example, is a landscape. This other one, which is genitals and a hand, is also a landscape. I don’t really see where the lines of separation are. But yes, sometimes the starting point is more about longing, about lack of contact…

It also happens that when I want something and don’t have it—even silly things, like a pair of shoes I love but can’t afford—I tend to paint them. I think with landscapes it’s the same. When I need something, painting it feels like a way to fill that gap, to generate worlds… I don’t know if I love that phrase, but yes, that’s the idea.

In fact, there’s a historical-artistic current that argues all creation is a projection of the creator’s desire.

I pretty much share that view. Yes, yes. There’s that phrase like “the lover always precedes the thinker,” which means that what we desire is what we create…

Of course, we can also project a very strong rejection trhough art, but still, that rejection is a different kind of desire, isn’t it?

I don’t think we can paint things we don’t long for or don’t have present in some way. And if there’s a way of doing it, of stripping ourselves of that, I’d love someone to explain it to me.

Many of your drawings are in pencil, a material that conveys a certain fragility. Are you interested in that feeling of the fragile, the vulnerable?

Yes, I’m very interested in minimal things. I don’t usually draw as much for final works, although in my last exhibition I did present a drawing. It explored the fragility of pencil, but I wanted to take it a step further: the work was composed of eight layers of tracing paper, each with a very fine pencil line, that when overlapped generated something different. In many of my large paintings I keep the pencil line showing outside, or even trace over it, because I think it maintains a certain freshness.

When I started studying, this was criticized a lot. Some more traditional teachers told me: “You’re coming from illustration, you’re doing something else, this is painting.” I took it as a strong critique at the time. But now it’s something I try to embrace. It gives me another perspective. It may be oil painting, yes, but oil is infinite. So when, instead of building up layers and volumes, you make a very thin, diluted layer, almost like watercolor, and enclose it with a pencil line… It’s still oil, but with another character.

I really love pencil. Sometimes I’d like to use it more. In my next works I think I’ll try to let it be more present. Sometimes it’s hard for me. It feels like, from self-criticism, I tell myself it’s unfinished, halfway done. I feel I’m not going deep enough into the technique. Maybe I still need to shake off some prejudices.

What I really enjoy most is leaving those blank spaces, that half-finished feeling.

In that sense, there are still certain canonical ideas today about what painting “should” be, a more academic or institutional discourse. Using pencil is also a way of doing whatever you like, right?

Yes, totally. Studying painting was useful for me to learn those kinds of rules, and maybe reject them a bit at first, then come back to them, keeping only what I enjoy.

But yes, they told me things like: “Don’t outline paintings.” Then, in one of the first drawing classes, we put all our works on the floor and no one could tell whose was whose. When they saw mine, the teacher said: “This person probably has dyslexia,” because it didn’t fit well. I burst out laughing.

Both the pencil outline, so simple, and the issue of proportion, are things that can still be criticized in academia, but which I’ve reappropriated in my work.

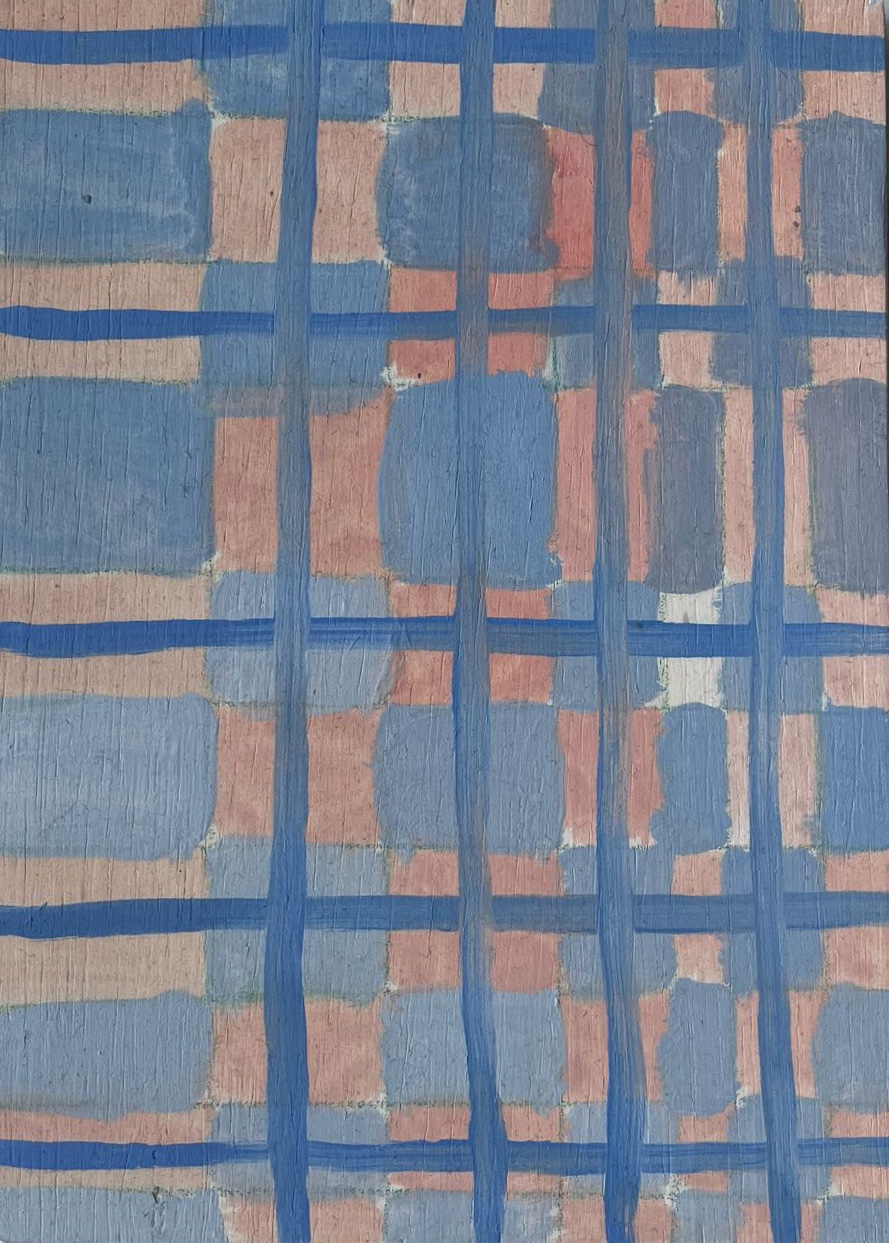

Along those lines, where do you think your interest in painting on wood comes from, a less typical material than, say, canvas?

Here in the studio, in the room next door, my colleagues work with wood a lot. There are always little scraps left over, orphaned pieces, that they give me. Some I’ve bought, but most are leftovers—you can tell because they have nails, marks… I like that, reusing them.

And, well, before I forget… iIt also helps me take off some pressure. When you work on canvas, on linen, with expensive materials, you’re more afraid. But when it’s something you found under a machine, tossed on the floor, you feel freer to play.

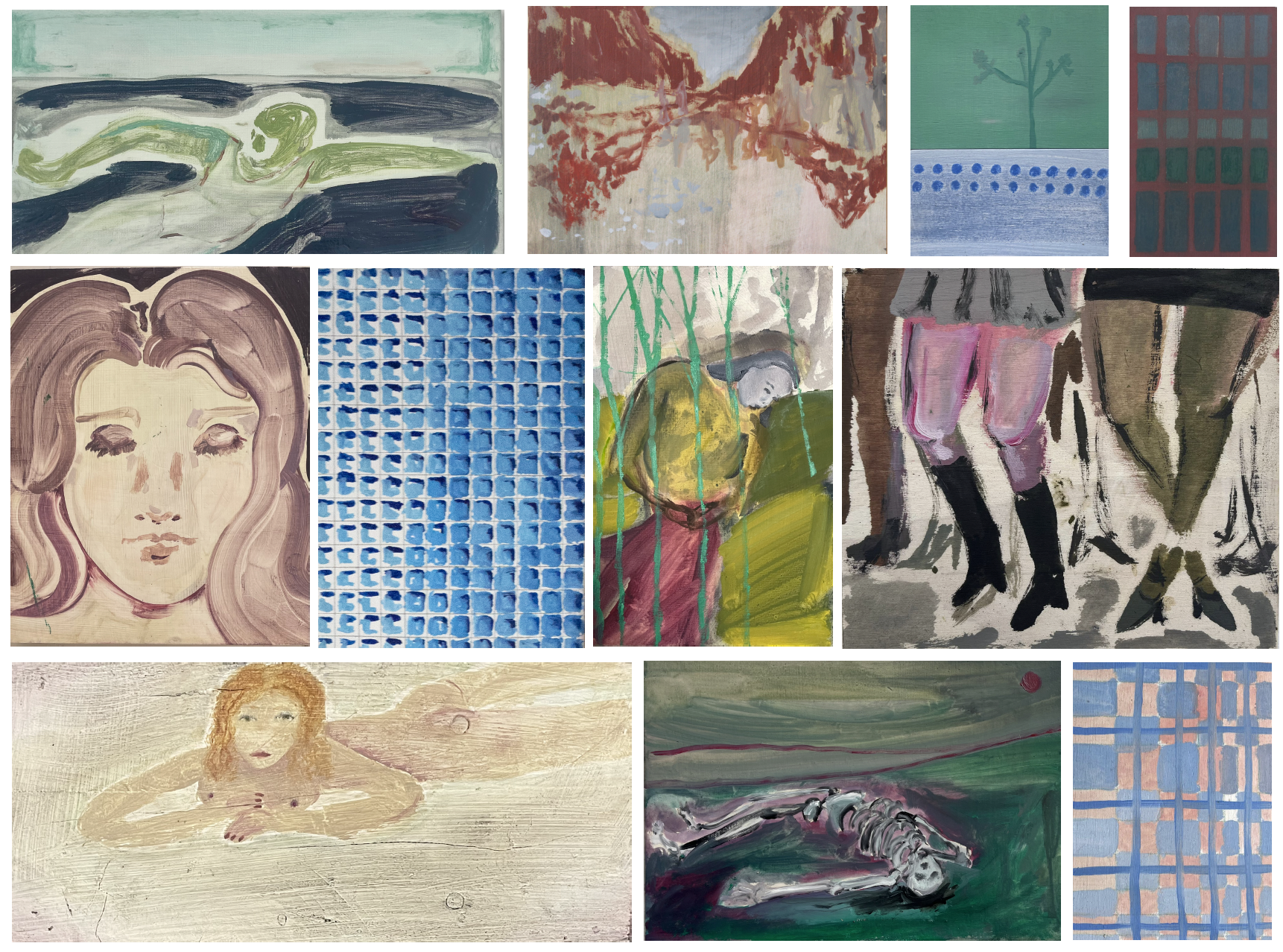

I get the impression that your small works have something fragmentary about them, as if they were parts of a larger whole. Is that intentional?

Yes, often I frame my works between two opposite poles: total distance or super zoom. I try to play between those two. Total distance gives images of characters floating in nothingness. Macro-zoom has a similar effect of diffusion and dispersion. Playing with both allows me to explore that line of emptiness, of lack of context or information.

I also feel there’s something of a window in them, an opening through which to look. Do you see it that way?

I love that you say this; I’d never thought of it before. I actually have an exhibition next year with a colleague. We wanted to create a house, and there were many ways to approach it. In the end, what will be seen in the paintings are the windows to the interior.

I’m always with my phone taking pictures of people from behind, as an act of watching from a distance, a bit voyeuristic, but shyly so. The phone ends up being a window, a separation between what happens and me, creating a certain distance. So yes, I think so. But I need to think about it more.

Another thing I thought the first time I saw your work in person—when the painter Álvaro García showed me the piece he had bought from you—was that it felt almost like a fragment of a diary. Do you see it that way, as something very intimate, unplanned, but very expressive?

That could also be, yes… Again, I hadn’t thought of it much. But now, suddenly, as you say it, it makes sense. Maybe I do treat small pieces more like a diary.

In the end, they’re usually images I don’t plan, but something I play with. Depending on how my day is going, one thing or another comes out. For example, this came from a book I found at my mother’s house, about parakeets. That day I came here directly and painted a parakeet. Another thing is that, even though they’re not planned, sometimes they work well together.

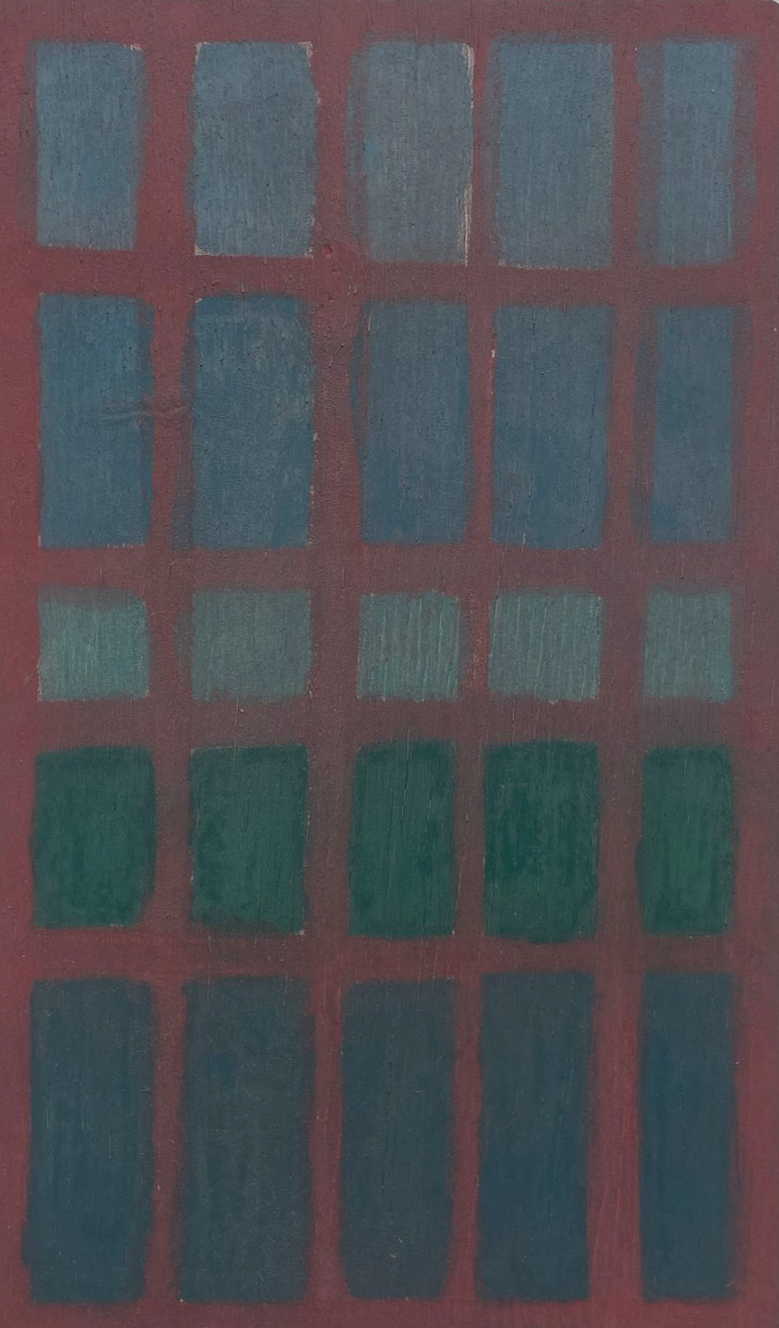

Yeah, I saw on Instagram that you arranged all of them together, as if they were a puzzle. Do you conceive them as a whole? Is there an intention to establish a narrative among them?

When I started painting on little wooden boards last time—that is, with the last batch I bought—I did all the sketches numbered, with the size each one should occupy… I prepared a very planned composition: color, shape, references, all that. Then I realized I was trying to reproduce what I had planned, and suddenly that geometric form ended up being… I don’t know, something completely different. So I couldn’t compose it as I had planned. I got bored.

But then I thought: well, maybe they can be composed in another way, just by making many and then seeing if they fit together randomly. Planning small-scale was quite hard for me. I felt a pressure I don’t really look for in that format.

So yes, some go well together, even thematically, but others I don’t know how to join. But I prefer seeing how things I made on different days suddenly fit together. That interests me more. I also enjoy calling my studio mates and asking: “How would you put this puzzle together?”

Earlier, when I saw the small works—both landscapes and those with repeated patterns and designs—I thought they conveyed something very musical, a kind of inner rhythm. Do you see any relation between your creative process and music?

Probably, yes. Because look, this is why my studio mates hate me: I play a lot of music, quite loud, and I always mix very different styles. What I paint changes a lot depending on what I’m listening to. It’s a bit like when you read a text with classical music in the background: suddenly it feels much more epic, like, “wow, this thing I wrote is amazing!” Then you take the music off and it’s not that impressive.

I imagine painting works the same way. Yes, there is a lot of rhythm, especially because they’re very fast pieces. They’re paintings that take me twenty minutes at most. So necessarily, there’s a lot of movement. And it may well be accompanied by the music, yes, probably.

In the process of creating these works with quick movements and involving your body directly, is there something therapeutic?

Yes, the small ones, I think, heal me a bit. They allow me to let go of control, which is something I think I need. There’s no pretension of creating a great work, or a big project. It may work or not. If it doesn’t, you flip it over and paint on the back, and that’s it. It allows me to loosen up and be present in the material, in the paint. That’s also why they have more texture, I think. Here, I don’t erase as much, and I also play more with color.

On the other hand, large paintings feel like the opposite—I suffer through them. That’s why I erase so much, why I sand so much, because I’m never satisfied. I keep removing and removing until it reaches a point where… Eric, my colleague, laughs at me and says: “Watching you paint a large canvas is like witnessing childbirth.” And it’s pretty much like that. Sometimes I even cry, though there are good moments too.

In the end, a large canvas is a space you can enter. A small one is like a little window into that place. But a large canvas can either invite you in or repel you, and that worries me a lot. I’d like people to want to enter my paintings. So I take them more seriously, but that makes me suffer, because it brings in full control.

The first layers I enjoy, because there’s movement, like in the small ones. The small works you paint on a table, contained. The large ones are more physical: you move your arm, bend down. I’m small, so I climb onto chairs. It’s another kind of bodily involvement. Emotionally it’s a challenge. Also because, sometimes, working with so little material, one extra gesture can’t be undone. And when it can’t be undone, it goes in the trash, because you don’t want to keep going. That puts pressure on me. That’s why I think the small ones are more therapeutic. I always try, when working on something big, to make several small ones at the same time.

Finally, any dreams or future plans?

Being able to keep painting for the rest of my life would be ideal. I don’t have big pretensions. Being able to devote myself to painting (and in my opinion, painting is something very broad, that encompasses many things) is something I aspire to, of course, even if it is in a humble way. In the times we’re living through, it’s a tough task. But I trust, and I understand, that it’s also little by little, like the work of an ant, a long-distance race.

If I had a big artistic dream, it would be to learn to paint well: to be satisfied with what I do, and for people to receive it the same way. That would be everything.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 06.10.2025