Valencia-based artist Gema Quiles welcomes us into her studio in the Benimaclet area, surrounded by half-finished paintings, small ceramic figures, and sketchbooks filled with tiny pencil drawings. She says she almost never plans what she does, but rather lets herself be guided by intuition and by the pure, simple pleasure of creating - and that she sees painting as space of refuge to escape from everything else. When we ask her about her upcoming exhibition at the IVAM, she says she doesn’t really know what she’s doing until after she’s done it. But, little by little, traces of what pulses through her work start to appear in her replies: intimacy, violence, desire, and the urge to soften what is harsh through a gentler, simpler language.

I’m not really sure, to be honest. Lately I’ve been listening to a lot of artist podcasts where people talk about how they always knew from a young age that they wanted to dedicate themselves to art, that it was crystal clear to them. And I thought: “What was I interested in as a child?” The truth is, I don’t know. I just existed. I didn’t have a specific vocation or anything I was obsessed with. But I think that in a way, that’s actually a good thing. The other day I was listening to a guy with an architecture channel, Eric Harley from “Periferia Periferia”, and he said something that made me think. He said he studied Fine Arts, not Architecture, and that precisely because of that he now loves architecture so much—because he didn’t have to suffer through it from the inside. And I thought that maybe if I had been a kid passionate about painting, going to art academies since I was little, I might have ended up resenting it.

Now I enjoy painting because I approached it without expectations, without pressure, purely from curiosity. No one pushed me, no one especially applauded me. And that’s how it happened—without drama, without grand plans. But I guess that’s also why it has become something so personal to me.

Artistically, living abroad has mainly given me the chance to discover new techniques I never expected. When I went to Poland, for example, I discovered ceramics. Although it wasn’t until Barcelona, during the Hábitat scholarship, that I really immersed myself in it. I think it was because the same ideas I had in painting could be materialised through that medium. I had never considered it before, simply because I had never tried it. Part of the magic of moving elsewhere is exactly that: arriving and letting yourself be surprised by what you find. Normally, I tend to play it safe, with a fairly clear idea of what I want to do, but when I’m in a new place I feel more open to experimenting and seeing what happens.

For example, at Piramidón, a residency I did a year ago in Barcelona, I had this wonderful moment to stop and really look at my work. I spent time reviewing sketches, observing, reflecting… It helped me much more than if I had just continued producing. Each place has given me something different: the opportunity to pause, to understand where I’m at and what I need at that moment. I think leaving the studio from time to time, discovering new places, and working in different contexts also gives you a new perspective on what you do.

Since November 14th you’ve participated in the collective exhibition “Disputa y Pausa” at the IVAM. Can you tell us how this project came about and briefly summarise what you’ve been working on for it?

This exhibition came from a programme called Arte y Contexto, which began in 2023 and has been developing over time. During the first year, we organised talks, conversations, activities… The idea was that all of this would eventually culminate in an exhibition.

That’s why the project carries elements from my previous exhibitions, although it also touches on new themes. It starts from an initial idea: the banquet, understood as excess, festivity, a moment of gathering. Over time it became contaminated with other things that also interest me, like the night from a more intimate perspective, something I had already explored in other exhibitions.

I like that mixture, because my idea from the beginning was to work with scenography. Presenting a banquet was, in a way, a way of bringing together elements from my past works: the table, the fruit, the harvest, the glasses, the shared moment… I wanted to bring it all together in one space and represent that kind of sensitivity simultaneously.

A beautiful phrase I’ve read in several of your texts is that you consider painting a refuge. What are you seeking refuge from, and why do you think art offers you that place of rest or protection?

It’s a complicated question. I think about it a lot and never arrive at a definitive answer. I do feel that painting is a refuge for me, but not so much in the sense of escape, rather as a space for introspection.

I feel that, just like with nature, painting allows me to rest, to take a step back, to stop looking so much outward—at the neighbour, at what others are doing… You don’t always know exactly what you’re taking refuge from, but you know you need it. Talking about visual oversaturation is super cliché, but it’s true: there are countless images, stimuli, people, art… And sometimes I need to disconnect from all of that, to shut myself in my own space and say: “I’ll stay here, I’ll make my little mountains, and we’ll see afterwards.”

I think my work has grown inside that refuge. Though when I try to explain it, I start feeling like an impostor and think: “Oh God, this sounds so silly.” But the truth is that painting gives me a place that calms me, even if I don’t know exactly what it protects me from.

In a conversation I recently had with another artist, he told me that painting somehow opposes the fast-paced way we engage with images nowadays, since it has a slower rhythm that allows you to enter a peaceful mental state. Do you feel the same way?

I think it’s absolutely like that. Painting requires a rhythm that you don’t control, and that also leads you to enter more deeply into it. Then you don’t really know how to explain it. I also think that when you paint, you’re in a way getting to know what you’re creating.

In that sense, painting becomes almost like a way of reading or listening to music, or understanding reality, but in your own language. And I think it’s inevitable to want to step away from other stimuli, because you need to focus on it with a lot of attention.

In your solo show “Hacia el Bosque, las Tormentas” at Herrero de Tejada gallery, you explored themes of war and violence by referencing an ancient legend. I also read a text where you explained that turning to more violent scenes was also an excuse to break or deconstruct your own pictorial language, right?

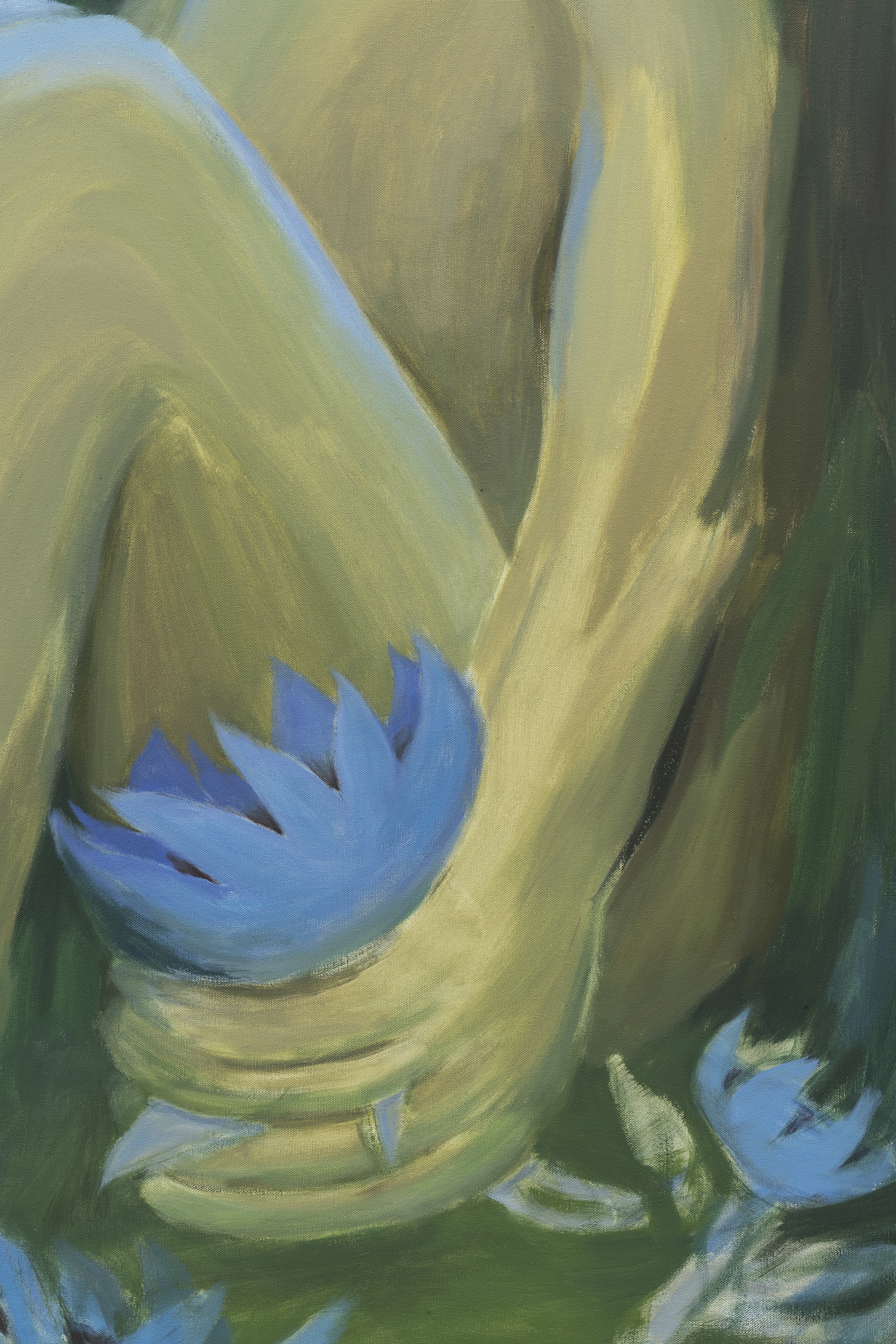

Yes, absolutely. For me, it’s often hard to separate the narrative discourse from the pictorial one. In that exhibition, for example, I felt the urge to break the figure, to integrate it into the landscape, to give it more dynamism, more violence… Inevitably, the words or images that came to me at the time were those: violence, battle, war.

That made the conceptual thread of the exhibition naturally revolve around the idea of a battle. I thought it was a very cool and poetic image, but there wasn’t any actual text or pre-existing story behind it. It had more to do with how I felt my work needed to express itself at that moment. Also with how I myself felt—almost fighting with the painting.

Would you say you were interested in appropriating typically masculine scenes and reframing them through your perspective as a woman painter?

I think so, yes, there’s something of that. I don’t think about it consciously, but I am interested in the mixture between the masculine—the harsh, the rough—and the sweet or delicate. Those points where the two intertwine are very present in my work. I like the idea of a battle that suddenly appears crowned with flowers. I try to use violence, but not to eliminate it—more to transform it. It doesn’t have to be violence in the historical or literal sense, but a sweet, emotional kind of violence. I’m very drawn to those contradictions.

During that exhibition I was reading a book by Amélie Nothomb, “The Character of Rain”, and then the second part, “Loving Sabotage”, which is about a war seen through the eyes of a little girl. The children create two sides, they capture each other, they commit “atrocities” that seem enormous to them, even though to us they’re just games. That mixture of innocence and horror seemed wonderful to me: how sweetness can sometimes be even more cruel than explicit violence.

I’m interested in that double contrast: that the viewer has to read between the lines, imagine things, complete what isn’t said. Sometimes, when something is presented delicately, it can be even more unsettling than something explicitly violent, I think.

I find it interesting that you draw on legends, myths, and fantastical stories in a world that seems to have lost interest in these narratives in favour of more rational or scientific ways of thinking. Do you look for a more magical or fantastical space in painting from which to express and understand things?

I think so. In the end, it’s a space where you can create whatever you want. And that naturally includes the possibility of falsifying anything. For example, I use a lot of symbols, but I don’t include them to refer to specific things. I use water a lot, fruits… But they don’t directly refer to reality. Within my work they have their own symbolism. That comes, in a way, from the idea of play—of creating your own fantasy, your own rules. And I think that’s exactly what painting offers: the fiction that reality doesn’t give you.

The different symbols I use—like water or lemons, which appear constantly—function almost as self-references. They’re recurring elements that acquire their own meaning, which transforms with each work. By repeating them in different scenes or moments, I use them differently each time, and that also shows how my practice evolves over time.

Continuing with that symbolic reading of your work, I believe that you differentiate between the forest and the garden. What do you associate with each of these spaces?

When I talk about the forest and the garden, I do it somewhat arbitrarily, although over time I’ve realised it makes sense. The garden appears when I think of something more structured, more ordered, more under control. The forest, on the other hand, leads me to chaos, to the wild, to what can’t be tamed.

For example, the exhibition I did at Herrero de Tejada revolved around the forest and dealt with conflict. And I don’t think it would ever have occurred to me to place that idea in a garden. It’s not something I think about from the start, but when I look back on it, it makes sense. In fact, that happens to me a lot: I understand my works more clearly once they’re finished. When I’m painting, I prefer not to analyse too much. If I start overthinking, I get stuck. I need to let it flow, and then later comes the moment to look and understand.

So, would you say you work in a very intuitive way?

Yes, totally. Sometimes even too much. It frustrates me because I’d like to have more control, to plan better. But I also know that when I let myself go and something unexpected appears in the painting, that’s when I enjoy it most and when the work feels more alive or interesting to me.

There’s also something Edenic or Biblical in the way you represent natural spaces. Do you draw specifically on those references?

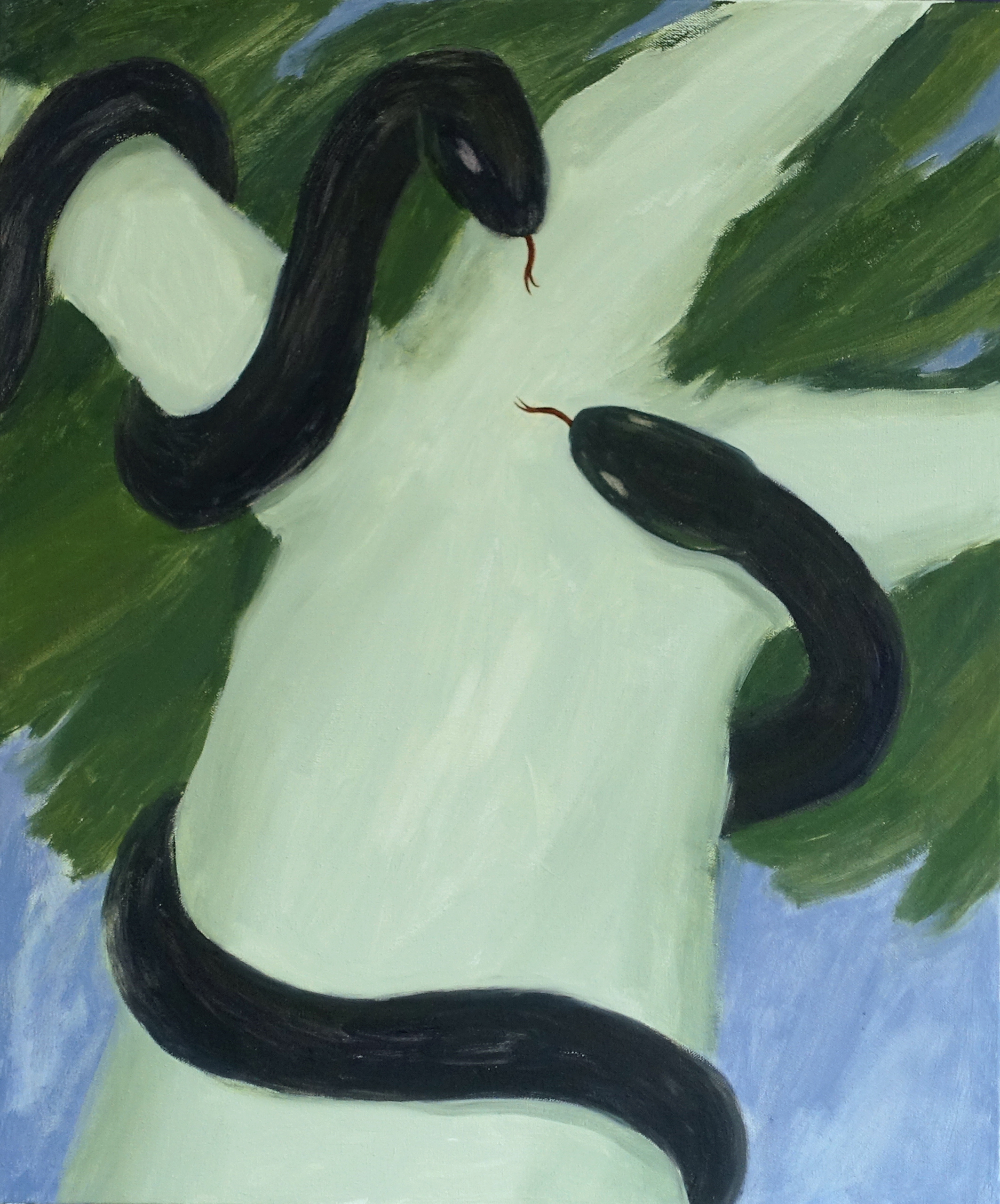

People often tell me that the elements I use feel very biblical or religious. And yes, I know, and it really amuses me; I find it charming, because in reality I don’t have a special interest in religion. My family is religious, but I’m not. Still, I can see what they mean, and it makes me smile. For example, in the last exhibition there was a snake with an apple. I didn’t come up with that out of the blue, obviously, but it wasn’t planned either—it just emerged. I’m sure it comes from many things that are there in the unconscious, in the images we accumulate.

My creative process is very much about observing, going out, collecting images, references… And then shutting myself in the studio to process everything and let it come out. That’s where these references start blending together. And I think that when you work with very primitive, very natural elements, very linked to essence, it’s inevitable that religious or biblical echoes appear. In the end, they speak about very primal desires and emotions, very inherent to human beings. That’s why it seems natural to me that these appearances get mixed up. And I like it—I think it’s really beautiful.

These symbols are associated with specific readings or concepts, but they can also be reinterpreted in painting through each creator’s personal gaze. Do you see it that way?

As we were saying earlier, they’re symbols that change depending on the context: depending on where you place them, they acquire different meanings. They can speak of desire, death, greed, love… Depending on the setting or the story you situate them in, they shift toward one meaning or another.

And that’s closely tied to fiction, which we mentioned before. For me —though I know it isn’t for everyone— the Bible, religion, is an incredibly well-constructed fiction. To me it’s the best of fictions. And painting or art, in a way, inevitably connects with it. I know it’s a controversial topic (I’m getting myself into trouble here), but it’s unavoidable: if you were born in a country with a certain religious tradition, you absorb those symbols from childhood. They attract you because they’re the first symbols you learn; they’re the ones that teach you what’s good and bad, what is sin, what is desire…

And of course, even if you reject all that in your teenage years, over time you look back and often find it interesting again. I think as the years pass you also start enjoying aesthetics you previously rejected or felt distant from, and I find that really beautiful.

Curved figures predominate in your work, regardless of what is being represented. Would you say that by unifying the forms through this visual circularity, you’re also leveling them thematically or symbolically?

I find that very interesting, because in my work you can’t clearly tell whether the figures are male or female; they’re more androgynous, hermaphroditic. I don’t know if it’s because I don’t feel ready or simply because I don’t need it, but I don’t feel like giving my characters faces. Sometimes I think: “Should I?” But then I feel that no, I’m not as interested in who they are as in what they do, what they generate, the movement they produce within the painting.

The feminine, the masculine — all those layers can be present in my paintings. There’s delicacy, violence, desire, intimacy… But since the figures don’t have defined facial features, you don’t really know where things are going. They touch each other, there’s contact, tension, longing, but no clear identity: you don’t know if it’s a man or a woman, nor does it matter. They’re more like primary desires or impulses, not specific identities. And that interests me a lot: I don’t want to impose a closed reading, but rather to allow that ambiguity.

I like the coexistence of opposites: a big, strong figure next to a more delicate or beautiful image, for example. For me they’re almost utilitarian elements, in the sense that they activate the painting, they make something happen. They don’t have their own identity or specific traits, and I think that allows them to merge more easily with the pictorial environment, to integrate better into the composition. Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to blurring the distinction between a human body and a tree, for instance. They exist on the same level. In the end, for me, both are painting in that moment. I don’t need them to have a defined personality, because what I’m looking for is for them to be just one more element within the whole.

From what you’re explaining, for you the most important thing is the very act of painting, isn’t it?

Yes, always. From the beginning, for me —and also for the people who guide me or who I work with— the main motivation has been painting. Wanting to paint, and gradually discovering what you want to paint and how you want to approach it. For me, all of this isn’t an excuse, but rather a place from which I can create, enjoy, and explore.

Regarding the naïve style that sometimes appears in my paintings, with that almost ingenuous or childlike feel… It’s not something I consciously aim for; it’s just what comes out. I could paint in another way, more “finished” or “better,” as my mother would say [laughs], but I’m much more drawn to a patch of colour, something suggestive, something that speaks to me without being fully defined.

I can admire technique and virtuosity, of course, but I’m more attracted to that direct language of gesture, colour, spontaneity. I’m interested in that naïve or even abstract aspect, because colour is what draws me the most in a work. And also, the more you touch something, the more you perfect it, sometimes the less you manage to say.

Another recurrent element in your work is the giant hands — imagery often associated with desire, longing, but also with its opposite: frustration, the inability to touch or reach something. Could you tell us about this connection between body and desire?

I think my work carries a lot of erotic and sensual charge, although sometimes I think maybe I’m the only one who sees it. There are no explicit scenes or anything that directly points to that, but there is something in the gesture, in the contact. For example, when you mentioned the hands, I thought: perhaps enlarging them, giving them so much presence, has to do with that tactile dimension, with desire.

Also, when I deform the figure, I’m interested in exploring how far I can push it without it ceasing to be recognizable. Sometimes I enlarge the feet or the hands, and to me it still feels natural, it still makes sense. I like to move along that boundary: to see how far I can go without it stopping being a figure, without breaking comprehension.

There’s also something very sculptural in the forms you paint. How do these two techniques relate in your work?

I think I inevitably see sculpture from a very pictorial point of view. I guess I force myself a little to maintain that gaze: to work with other materials but with the same mindset I have when painting.

It’s not about literally translating an element from the canvas into space, but about building with volume and material the same logic that exists in the painting. Do I achieve that? I don’t know, but I enjoy trying.

Also, I don’t consider myself only a painter. I’m interested in creating, in general. Being able to expand the pictorial toward other forms and materials feels incredibly rich. And when I work in institutional contexts —where there isn’t the commercial pressure of sales— I allow myself to experiment more. You can develop projects that don’t need to be “shippable” or durable, but that simply exist.

My figures, in fact, have something sculptural: they’re like mastodons, almost clay dolls, as someone once told me. I loved that comparison, because that’s exactly it: figures made in the most direct way, with arms, legs, torsos, and that’s it. Something very primitive, very essential. I’m drawn to that connection with the elemental, with the most basic symbolic language.

Moving to more general topics… As a young artist, how do you see the panorama of emerging arts in Spain?

From what I hear, it seems we’re in a moment of crisis. And yes, in part you can feel it. In the fair or gallery circuit, you sense a kind of stagnation — less movement, fewer risks being taken. But at the same time, I see a lot of underground proposals emerging, especially here in Valencia.

There’s more energy, more desire to do things outside of the market. It’s really stimulating: self-managed projects, collaborative initiatives, full of freshness. Even though they’re not driven by economics, they’re offering very interesting perspectives.

So, is it true, then? Is the emerging art scene in Valencia really so active right now?

I was just talking about this with a colleague recently. In the last few years, I’ve noticed more young people wanting to gather, to do new things. Before, I saw it all as more closed: each person in their group, in their studio, without much connection. I think that’s changing.

I think that in moments of precarity, interestingly, you also see a stronger urge for community, for claiming spaces where things can happen. I wish a complicated context weren’t necessary for that to occur, but yes: it’s generating movement, and that’s very stimulating.

And, to finish: any dreams or future plans?

Honestly, being able to live off this would already be a big dream. But what I like most about this profession is the freedom it gives you: the possibility of constantly learning new things.

When I picture the future, I imagine myself having done many different things, not necessarily just painting. I like the idea of being an expert in nothing but having touched a bit of everything. Today I’m into painting, tomorrow ceramics, the next day video… My ideal is to keep creating, learning, experimenting.

One of my dreams, for example, would be to build my own house. I’d love to do it from scratch, at my own pace, with my own hands. Even bringing an artistic approach to the process, because that learning is also creation. I imagine myself like that: living quietly, surrounded by my things and my projects, enjoying the act of making and learning.

Interview by Victoria Álvarez Conde. 03.12.25