As we speak, Peruvian artist Raúl Silva unfolds before my eyes an impressive collection of objects he has gathered over recent years—so extensive that his studio practically resembles the back room of a historical archive. Holy cards, bulletins, nineteenth-century maps, and clippings from old newspapers trace commercial relations between Europe and Latin America over the last few centuries, laying the visual groundwork of his artistic practice.

Somewhere between historian and artist, between the curve and the straight line, Raúl Silva’s work examines and transforms the visual development of certain socio-economic practices that have shaped our technified and globalized society. Here is a small portion of our conversation:

Hello, Raúl! You’ve mentioned that you feel you can be pigeonholed in Spain as an artist who deals with colonial themes, and that you wouldn’t like that to eclipse the rest of your interests. Within what broader spectrum are you interested in situating your artistic practice?

Hello, Raúl! You’ve mentioned that you feel you can be pigeonholed in Spain as an artist who deals with colonial themes, and that you wouldn’t like that to eclipse the rest of your interests. Within what broader spectrum are you interested in situating your artistic practice?As a Peruvian migrant in Spain, colonial discourse appears very frequently. Today it has a strong presence, especially in institutional formats and within the gallery circuit, where reivindicatory dynamics—particularly in the Peru–Spain relationship—have gained greater visibility. These are premises I feel aligned with; I don’t deny them. However, it’s also true that this framework ends up overshadowing other interests of mine that are not exclusively tied to that historical relationship.

I’m also interested in a broader critique of the contemporary political-economic system, or in addressing issues such as global forms of distribution and technification. That is precisely where I want to insist and strengthen my position. I place importance on this because these axes have gradually pushed my practice toward other media, such as video and graphic design.

Before moving to Madrid, you lived in several different countries—for example, in the Netherlands. How have these changes affected your development as an artist?

Interestingly, although I was already working on themes related to Peru while I was still living there, it was only after leaving that I began to take a deeper interest in them. Being abroad, people asked me questions I had never considered—about Peruvian artists, historical genealogies, and so on. I realized I had many gaps in my knowledge. Not only regarding historical or artistic milestones, but also more profound issues that aren’t easily found online.

That realization led me to delve deeper into topics such as guano. It’s a very well-known subject in Peru, but revisiting it from outside the country allowed me to approach it with a different kind of meticulousness. Migration enabled me to reconcile with things I already knew, but from another position, with greater depth and perspective. It also pushed me to understand that the history of Peru is not an isolated one, but rather part of a global network of economic, political, and cultural strategies that are relevant beyond colonial critique.

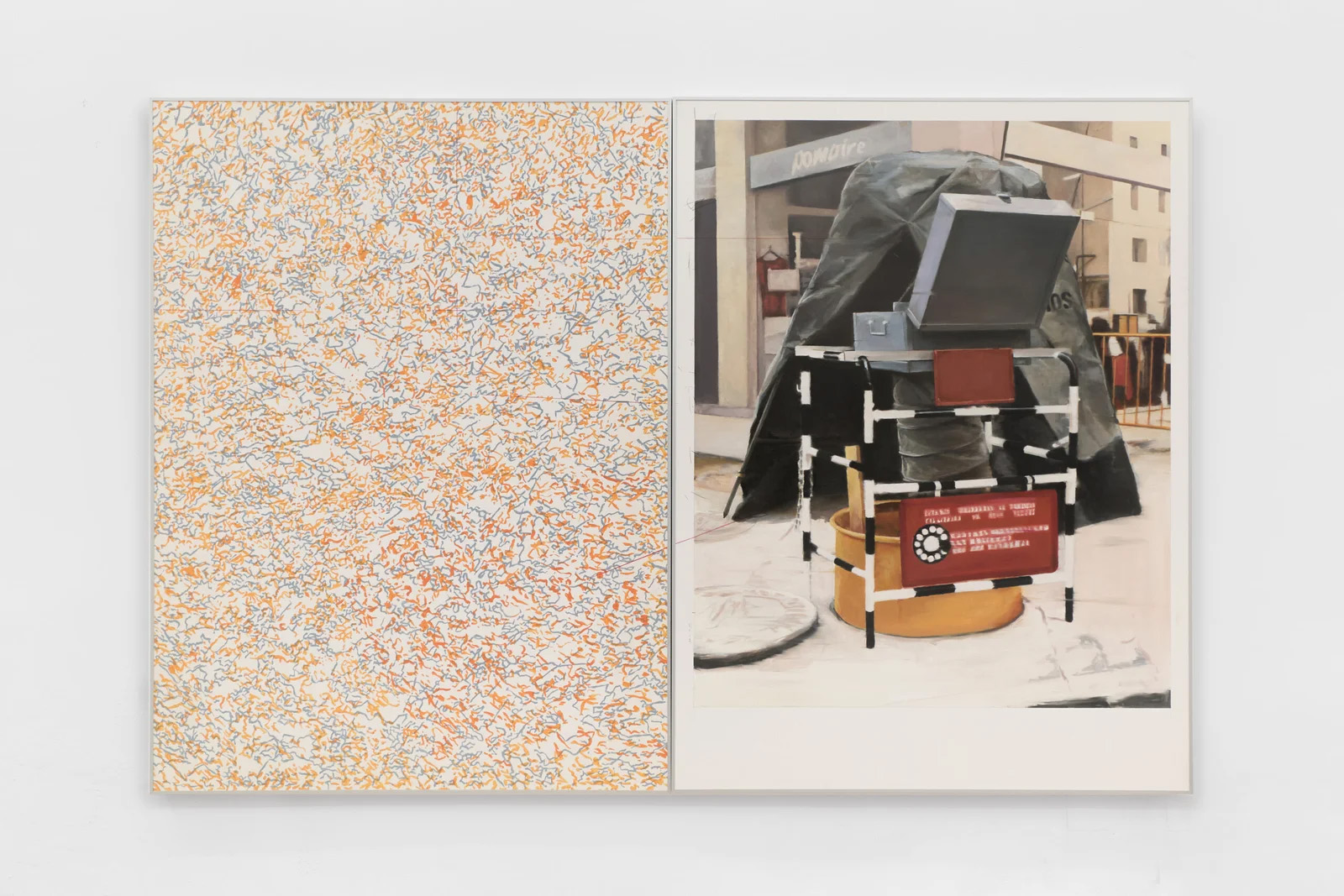

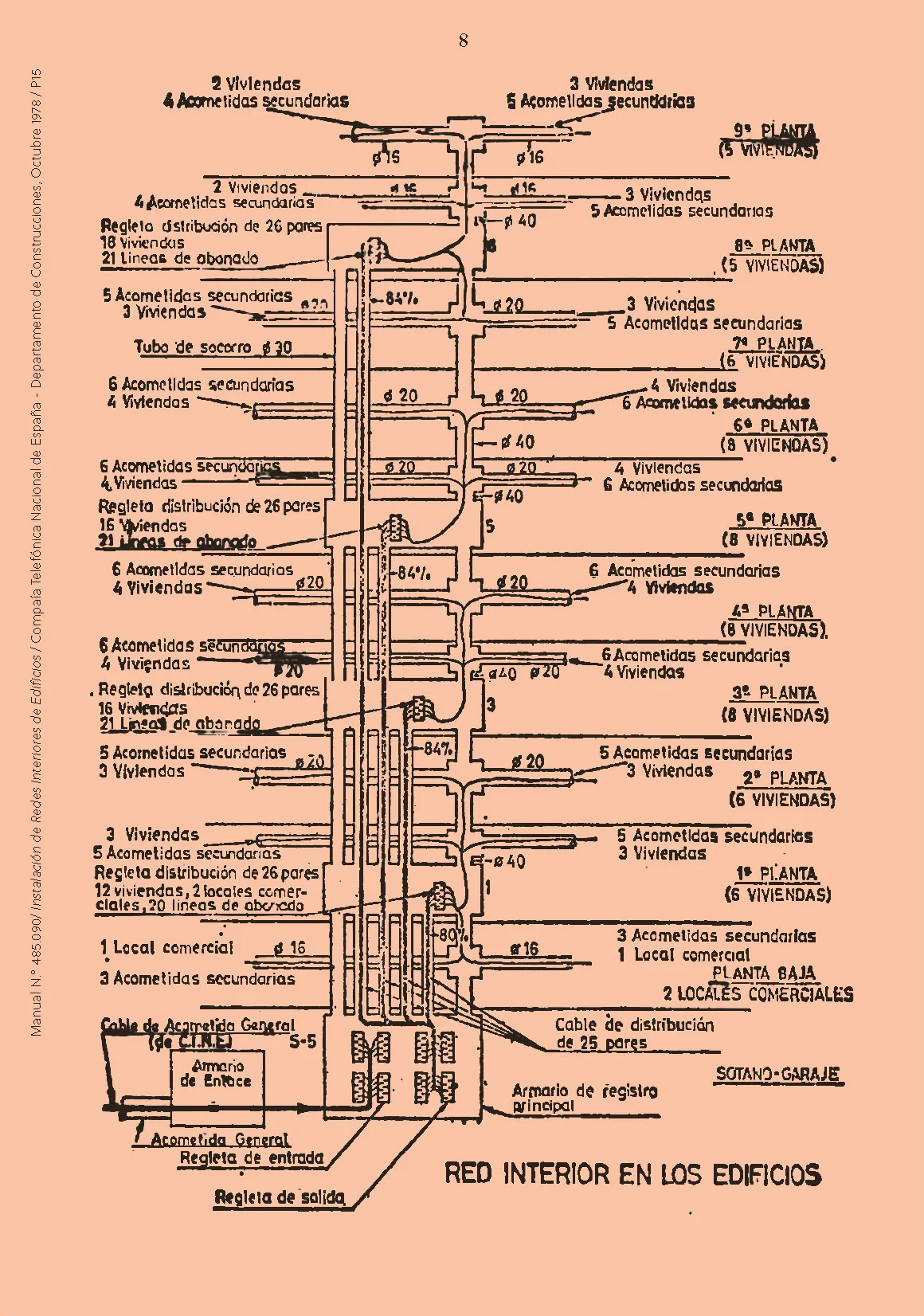

This is the first project in which I step away from the history of Peru, which had been almost a constant idea in my work, and it’s very much related to my move to Madrid. It wasn’t immediate; the idea took shape two or three years after I arrived. It has to do with trying to understand how telecommunications are represented in Spain.

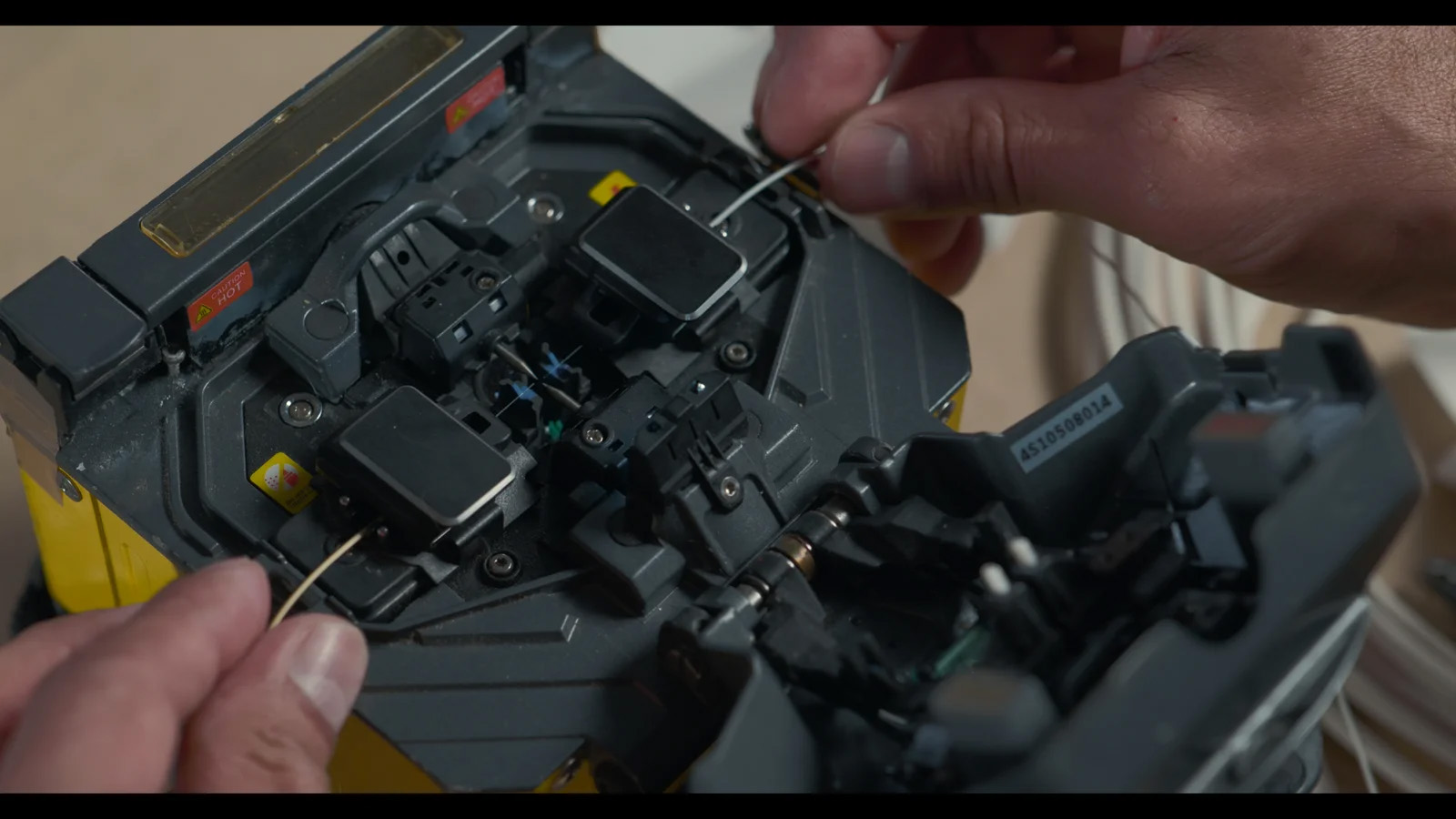

What I’ve done stems from a working methodology I draw from The Submarine Cable Network by Nicole Starosielski. This book uses case studies of various telecommunications hubs that connect the Atlantic and Pacific to the United States. Through these cases, it proposes an almost ethnographic reading of how certain technical communities are formed around these nodes, and how their dynamics are established and represented. It analyzes, for example, how operations are carried out in territories that function as colonies: how bases are set up, policies established, and forms of control enacted. The book also includes several sections devoted to communications, where it reflects on internet cable infrastructure as a historical continuity that traces back to the telegraph and is also linked to telephony. In a way, it points to a tendency to conceal these infrastructures.

And what have you found in your research on how this reality is represented by companies like Telefónica?

Building on Starosielski’s ideas, I review Telefónica’s archives in order to look for evidence in the Spanish context that may lead to the same conclusion.

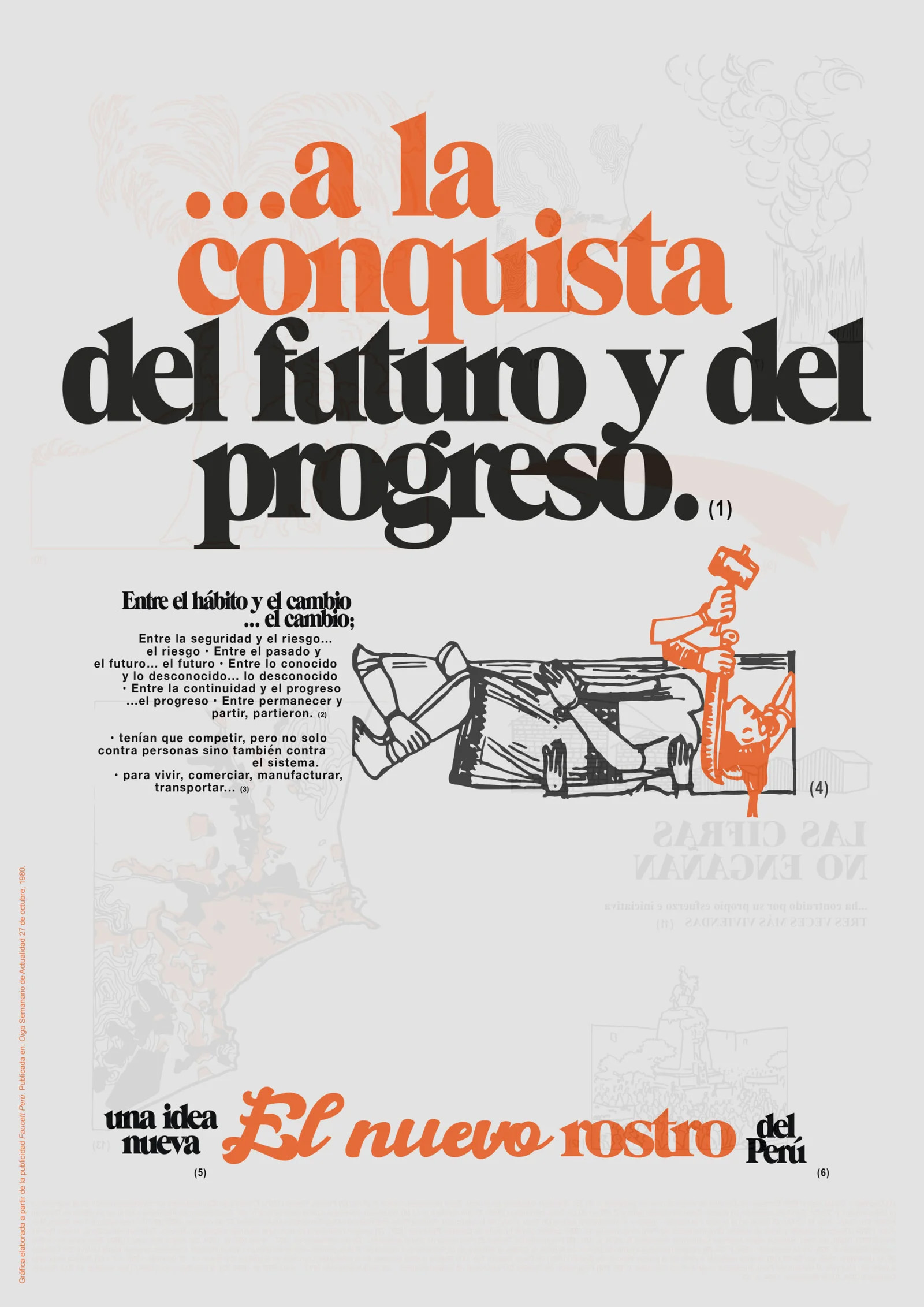

From a research standpoint, my methodology is somewhat flawed. I haven’t conducted a thorough review of sources to arrive at conclusions specific to the Spanish context; rather, I start from those existing conclusions and then look to see whether they also manifest here. I’m not drawing firm conclusions, but I’ve found information in the digitized archive that I find very interesting. For example, advertising from the 1960s and 1970s—available online—that links telecommunications to the transformation of users’ experience of space and time.

What conclusions do you draw from this?

We know that the cables exist, we know they’re there, we know how they work, but they are absent from our visual imaginary. They don’t appear in advertising or in any form of communication. Instead, what we do see is an almost self-evident assumption that communication is sustained via satellites: halos of light, a dematerialization of infrastructure, increasingly smaller devices, and a language that appeals to the ethereal—terms like cloud or wireless. That’s the world we’re surrounded by.

It’s interesting because the telephone is associated with moving faster, doing things in less time, not having to physically go somewhere in order to be there—if not physically, then at least in consciousness. Even the imagery sometimes has a distinctly divine, metaphysical quality, almost as if the body connected to the communications system were being elevated or displaced. I find that fascinating. The cable is still not represented, the infrastructure is still not represented, and it seems that during this period there is a kind of directive around this transformation of human experience.

Through research like this, do you also aim to show how these companies seek to make their environmental impact invisible?

It’s not something I’ve examined in depth in terms of data. But of course, the fact that servers supporting today’s AI systems need to be submerged in the ocean for cooling, or require enormous amounts of water for refrigeration—and that this has an environmental impact—is undeniable. There is also very limited access to servers, partly for security reasons, and because data centers are strategic infrastructures, for instance in the event of conflict.

So there’s this issue of where to place certain devices, how to hide them, almost as a corporate policy. That’s something that interests me as part of the premises under which the system operates in general, not just telecommunications. Clothing production, the fetish of the commodity, who makes the T-shirts for certain brands—almost all of them. Where are technologies produced? How do information vectors triangulate suppliers, producers, and exploited workers to generate profit? I think it all follows the same logic. In the end, it’s almost about talking about the same thing.

Yes, I think that, in many ways, this is present in my most recent projects. Perhaps not in a fully conscious way, but rather as a constant attempt to understand how these processes are configured.

Now that you mention it, I’m reminded of an author who influenced me greatly: Allan Sekula. I’m particularly interested in Sekula when his work is read through the concept of cognitive mapping. This idea has to do with the possibility of mapping the hidden structures of the system—structures that operate behind our backs and at a speed we’re unable to perceive. While the world functions and transformations take place that determine our way of existing—the ground we walk on, the walls that surround us, the materials we use—we remain trapped in the immediacy of our basic needs, almost as if everything else were happening by magic.

Faced with this impossibility of comprehension, Sekula’s work seeks to make visible specific infrastructures such as ports or shipping containers. He also reveals that these infrastructures involve energy, labor power, and elements of subjectivity—sadness, nostalgia, affection—linked to things we normally don’t perceive.

In a way, I understand my recent work from that perspective. Not so much through painting, but especially through video: trying to make visible certain realities that usually remain hidden, putting them into circulation, making evident that things are happening. And not only from an informative standpoint, but also by attending to the symbolic spaces generated around these infrastructures.

In the work on cable networks, for example, beyond advertising or a macro observation of the system, I was interested in manual practice: everyday technical labor, accumulated knowledge, experience, working conditions—but above all, the sensory dimension: the relationship people establish with materials. Without that material and tactile relationship, cable infrastructure could not be sustained. It’s almost a biological relationship of mutual dependence.

I feel that your work constantly sets up a tension between presence and absence, matter and emptiness, even on a visual level.

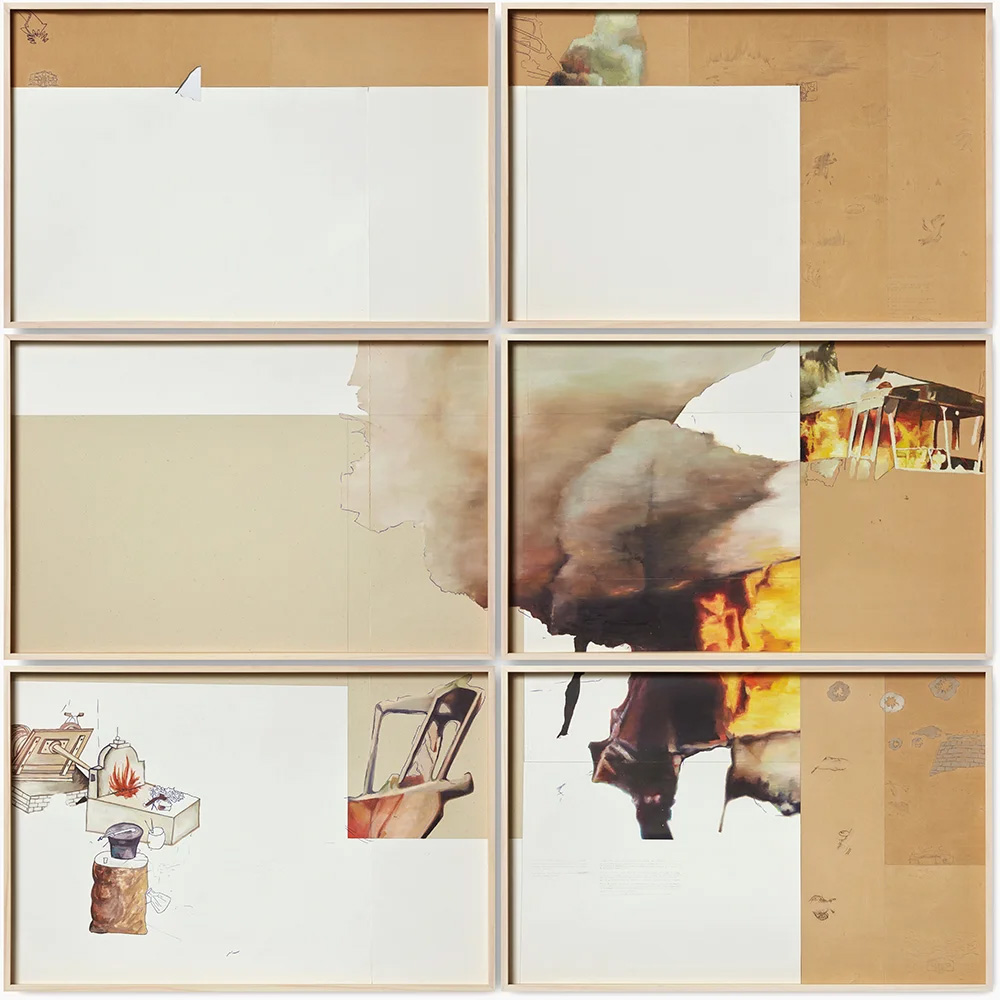

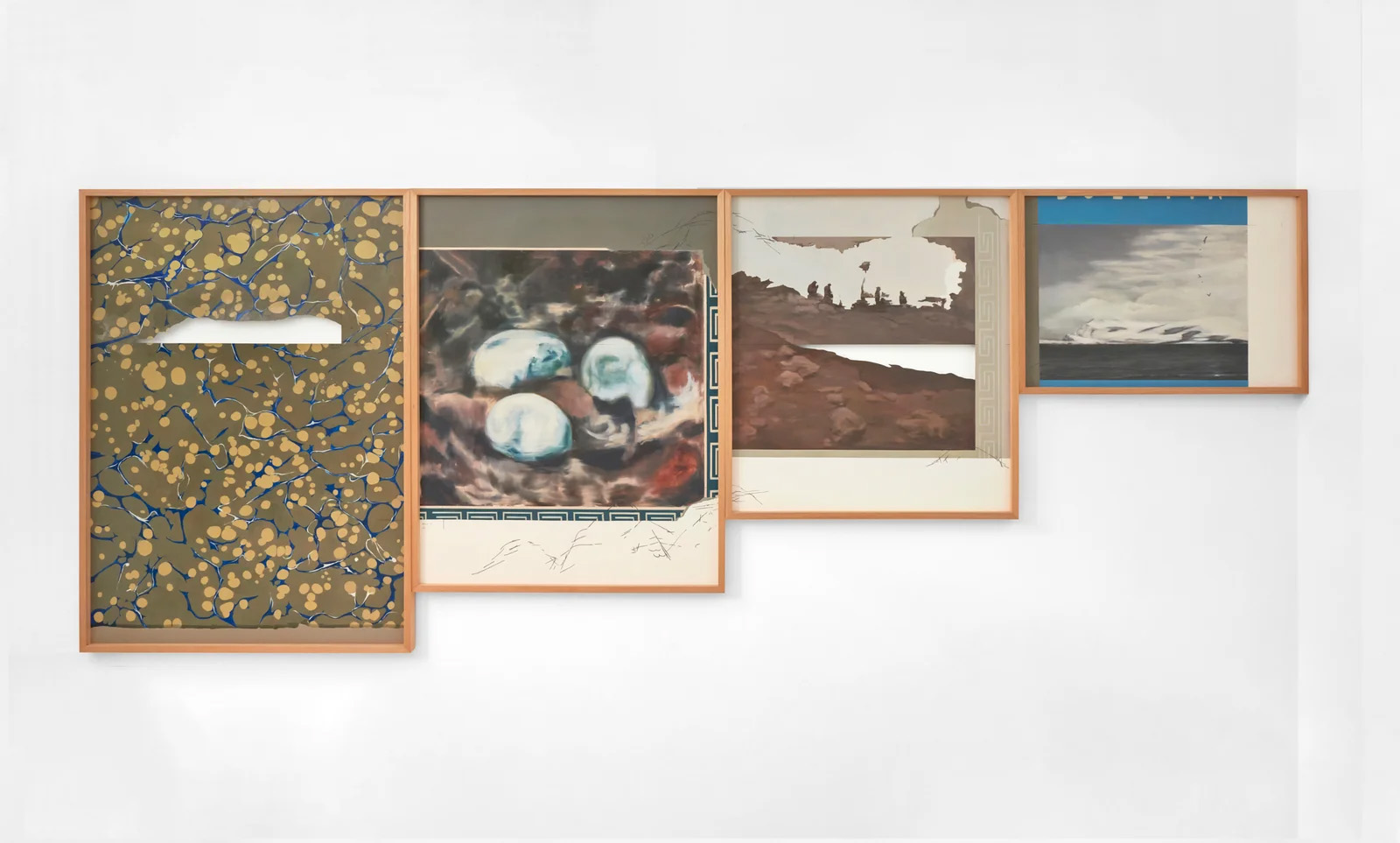

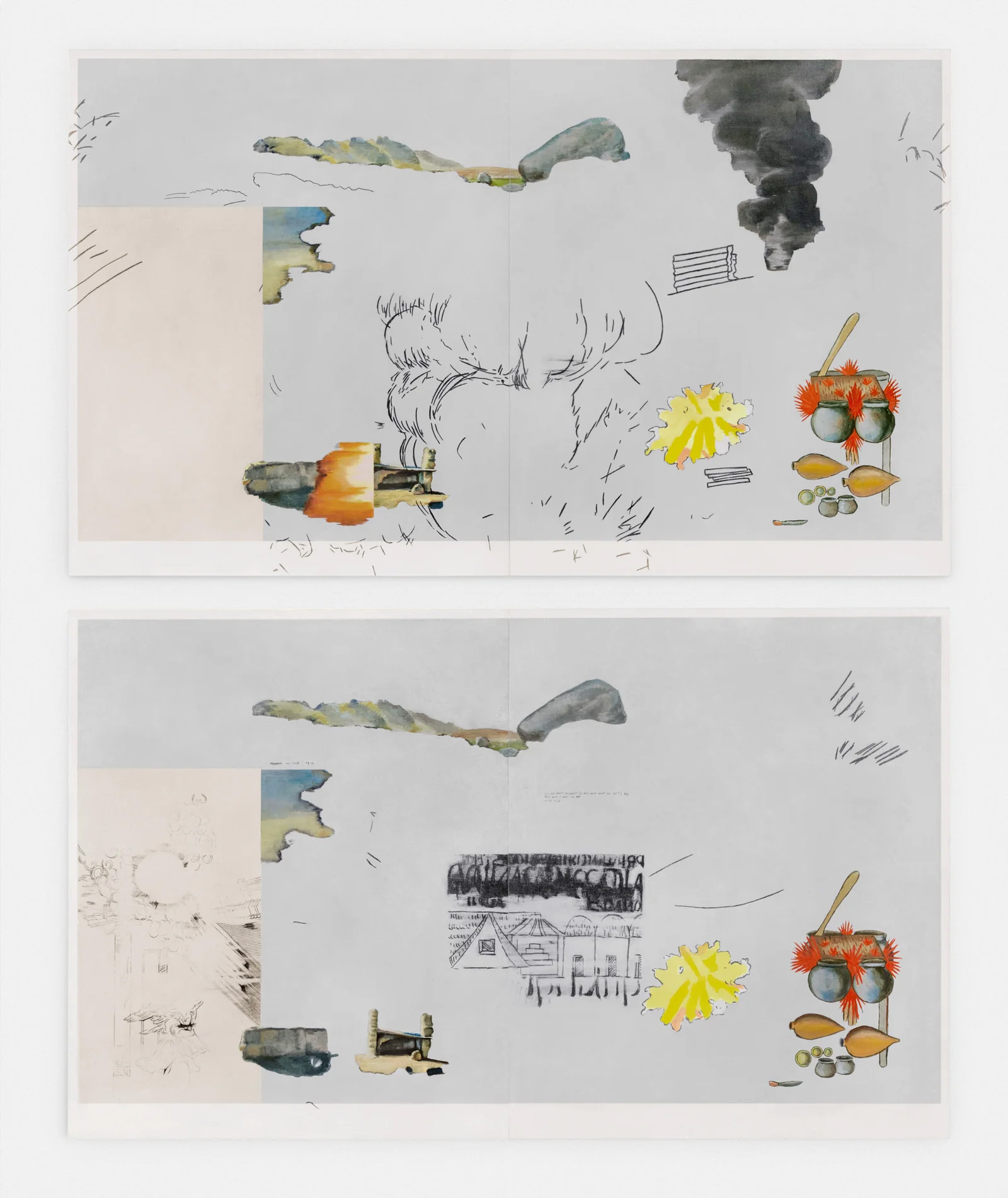

Yes, I see that. I think I started working that way around 2015 and I haven’t stopped since. I suppose it has a lot to do with the logic of collage and with this idea of removing information. When you decide to eliminate something from an archive or an image, what remains still has to communicate. If there is no void, there is only an object, an icon. So the void has to communicate its absence in relation to the object. When I remove the context from something, I try to make that void activate what is missing.

There’s a piece that isn’t online and would be difficult to show today, but that was very important to me. It relates to a series of Sarhua boards made by artists from the community of Sarhua, in Ayacucho (Peru), which narrated how military forces and the Shining Path entered their town during the 1980s. These works were acquired by an international institution and later donated to MALI, returning to Peru in 2017. Upon their return, the Public Prosecutor’s Office temporarily seized them under an investigation for possible “apology for terrorism,” due to the presence of elements such as communist flags, weapons, or military figures. This sparked a huge public debate. The Lima Art Museum had to justify that the works constituted an impartial narrative and a cultural object recounting the history of the community itself.

Within a context in which political discourse does not hold the military accountable for the executions committed, the regulation of what can be said and how memory of the past is constructed is very strong.

My response was to produce a painting on wood in which only the elements for which the work had potentially been confiscated appeared: flags, weapons, helmets, a helicopter… All arranged in their original positions, surrounded by a vast emptiness created by the erased absences. The work bore the same title as the Spanish translation of the original series: Who Is Guilty? (originally “Pirak causa”). For me, the void functioned in the clearest possible way there: it allowed me to speak about conflict, censorship, violence, and responsibility without representing everything explicitly. That piece became a methodological model for my later work—not so much narratively, but as a strategy of fragmentation and absence, something that is still present in many of my current works.

I don’t know if you’re familiar with the work of Nicholas Mirzoeff, a British theorist who writes about the power of images as political agents and about the right to look—about what is hidden and what is visually shown. I get the sense that visuality is also very important to you as a transmitter of discourse today.

Absolutely. I think there has been a shift since the arrival of photography, especially since its democratization and the prioritization of cameras and mobile phones. This was already anticipated by Walter Benjamin, who understood early on that this would have a significant impact. Today, I think it’s a reality: not only within cultural studies, but even within philosophy, almost all recent lines of inquiry are beginning to emphasize an aesthetic dimension.

If I think quickly of figures like Toscano or Jameson, they are important references for me because of the place they give to visuality and aesthetics within their theories.

It’s funny that you say that, because I feel it’s the opposite. My original training is as a painter, and I come from a moment very closely tied to abstraction and formalism. Gradually, I began to understand painting as a form of reappropriation and reproduction in Peru, which led me to question what exists in an image beyond rhythm, composition, or color.

That process gradually led me toward curating and then toward an interest in history. I try to maintain that relationship between an intuition about certain things happening in history and the image. What I feel is happening to me now is that media like painting are falling somewhat behind in terms of distribution, communication, and reach. At times I feel increasingly uncomfortable with painting and more comfortable with design and video—media with which I feel more ideologically aligned, even if they satisfy me less on a purely formal or plastic level.

Why are you drawn to these mediums?

I think because they can circulate much more widely, which feels more consistent if I’m undertaking a research process. A painting might be seen by people online, but materially it ends up being bought by two individuals and stays in one place. Design, on the other hand, can be more plural—anyone can have it, modify it, carry it with them.

I also think a lot about the materiality of these objects or designs, and about their more painterly details. Over the past two or three years, I’ve become very interested in video—understanding the textures you can achieve through the camera. I’m discovering things there, and I feel like I’d like to go deeper into that, even though it remains a constant internal debate.

More specifically, how does a research topic begin in your work?

I think I started with a topic a long time ago, and that topic began to travel on its own. For example, my research on the Chincha Islands almost immediately connected with submarine cables. Even before the islands, I was already working with the relationship between the desire for progress and the contradiction that this desire can generate. Understanding that the idea of progress is ideologically ingrained—even though it’s difficult to accept, given its connection to the impulses that drive today’s economy. That conflict is still there.

In your installations, I get the sense that you’re trying to create a kind of scenography that contrasts an ideal image with a material reality. Are you interested in that kind of staging?

Yes. In my most recent projects, that idea has been very present: an ideal image and, in contrast, a material reality or an infrastructure that is revealed. I’m very interested in how the viewer interacts with this in terms of scale—how they move around it and understand what dimension I’m referring to. The scenographic aspect has to do with orienting the viewer’s senses within the space.

For me, this goes far beyond the idea of the painting as a window. Creating an atmosphere is complex, especially due to technical and economic constraints: lighting, projection, the coexistence of painting and video. There’s always a need to negotiate and find a middle ground.

In For the Sake of the Future (Por el Bien Futuro), you address the idea of progress through your parents’ past in rural Peru. In this and other works, a tension appears between the urban—associated with progress—and the non-technified rural world. Is this a relationship you’re interested in exploring?

Yes. This project explored the relationship between migration and progress, not only in Peru but in different contexts where a clear distinction is established between rural and urban. If the prevailing assumption is that the “future” lies where there are universities, jobs, or institutions, then migration will appear as the ideal path to undertake social and economic progress.

One arrives in those places with a set of values—love, care, affection—that underpin these displacements and are closely tied to family protection and survival, but also to a very strong affective dimension. These are values we might consider intrinsic or noble, yet they end up sustaining dynamics such as competition, acceleration, constant work, and in many cases the abandonment of certain cultural rituals.

Language, for example. Stopping speaking Quechua. My mother knew some Quechua words and my grandmother spoke it fluently. My mother abandoned it in the process of migration, and I don’t know Quechua at all. She once taught me how to count to ten, but today I don’t remember any of it. All of this is part of a process of transformation.

I grew up with these ideas. I went to Chiquián, my mother’s town, only two or three times in my entire life, and I think about the differences—about how the current context pushes you toward other kinds of dynamics that shape you within a space of competition aligned with the contemporary economy that sustains the system, a system I rationally critique.

Within migration there is a contradiction that, for me, functions almost like a dead end: on the one hand, the family values that drive these decisions; on the other, the actions you take—supported by your environment—that reproduce a very specific cycle: going to school, studying at university, doing a master’s degree, entering the workforce in a company. A closed dynamic. I think all of this is what I try to address in the video I made about four years ago, titled For the Sake of the Future. It puts forward this idea of the systematization of production, the acceleration of the system, and a notion of progress that seems to demand the elimination of a past that does not allow for exponential growth.

Ultimately, these reflections also seem to stem from a very personal place—from observing your mother’s experience and your own life.

Yes. All of this is deeply connected to my personal history and to the Peruvian context, which is marked by a process of colonization. That process erased the possibility of reaching a different cultural and economic horizon. I’m not trying to say it would have been better—we don’t know—but it certainly would have been different. There would have been another notion of space, of practices, of our relationship with the world.

Today, there is a certain consensus around the idea that it might have been a more conciliatory relationship with nature, but I wouldn’t assert that with certainty either. What we do know is that it would have been different.

Yes—actually, that idea appears in a curatorial text for an exhibition I’m participating in, curated by Alejandra Monteverde and Alexandra Romy at Unanimous Consent. The notion that time always moves toward something better, that society is destined to grow continuously, is not universal. Stasis, repetition, and cyclical relations were also deeply internalized ways of life. Today it may seem inevitable to think outside a model of progress, but that model is a historical construction, closely tied to the rise of capitalism.

I wanted to talk about Weak Universalism, a piece that highlights a very stark contrast between vegetal or natural imagery and more technical—or in this case, evangelizing—images. Do you establish that distinction consciously?

Yes. First of all, regarding that project—the one I recently exhibited at Atlas—there was something that particularly interested me: the reproduction of images. If you look at my work, nothing I paint comes from a mental image; I always start from something that already exists.

The piece emerged from the fire at the Church of San Sebastián in Cusco in 2016. Inside was a monumental series by Diego Quispe Tito, composed of six diptychs narrating the life of Saint John the Baptist. Five of those pairs were lost in the fire, just a few years after the church had been restored.

What’s interesting about these works, characteristic of the seventeenth-century Cusco School, is that they integrate local flora and fauna into Christian imagery. Quispe Tito worked from European engravings—mainly Italian—that arrived at the diocese. From those black-and-white images, he constructed painted scenes in which the landscape, trees, animals, and even the angels’ wings—painted like parrot wings—came from his own lived experience.

Art history understands this as a key moment of pictorial syncretism. I try to read these images also as a kind of prediction: a local natural ecosystem dominated by Western infrastructure and a Catholic mythology foreign to the territory. It’s as if a new world suddenly landed in a space that doesn’t belong to it. I work with that tension in my paintings.

In later projects—for example, the one currently on view at Crisis Gallery in Lima—I reproduce the ten pieces at a smaller scale. I begin selecting elements so that there is a constant dialogue between nature, infrastructure, technology, and materiality. Weapons, cloaks, water, sky appear more clearly there. That forced coexistence between systems is, ultimately, the foundation of the entire project.

In your guano project, you mention the relationship of scale between mountain and human figure as a symbol from a Western perspective. How did this idea emerge, and what have you been researching around it?

It was actually my professors of contemporary art history and visual culture who pointed it out to me. When I showed an image of a guano mountain about thirty meters high alongside three workers extracting it, one of them told me it reminded her of old photographs of the Egyptian pyramids—images that oppose the immensity of nature to the smallness of the human body. Not so much as a romantic exaltation of nature, but as a way of representing domination over something larger than oneself.

That observation accompanied my research on guano and helped me better understand the Romantic spirit Humboldt constructs in his writings, as well as the impulse driving early nineteenth-century scientific naturalism. At that time, nature wasn’t approached only as an object of scientific study, but also as a poetic, almost mystical experience.

What interests me is how that poetic image transitions into a technocratic representation: one centered on quantification, data, layers, density, chemical composition—how much remains, how long it will last, how it will be extracted. That transformation also entails a radical shift in modes of representation: from the colossal to the microscopic, from landscapes to samples, grains, textures, classification. In the case of guano in Peru, this shift is very evident, especially when you look at scientific journals from the period: large images on the covers, and inside, an obsessive attention to the small.

In that study of guano, you talk about creating a polished image, very much in tune with contemporary visual culture. I’m interested in the relationship between polish and an idea of progress that today can even seem harmful. Do you recognize yourself in that tension?

In that study of guano, you talk about creating a polished image, very much in tune with contemporary visual culture. I’m interested in the relationship between polish and an idea of progress that today can even seem harmful. Do you recognize yourself in that tension?Yes, I agree. For me, this idea of polish is closely linked to digital and vector-based imagery, which starts from synthesis. The idea of synthesis—an heir to the Bauhaus, signage systems, modern typography—tends toward universalization. In contrast, ornament, decoration, or specificity respond more to individual imagination. This synthetic visual language aligns very well with ideals of globalization and with the growth of the economic system. When I think of polished images, I also think of aseptic spaces, of the perfect photograph in advertising—say, a green avocado against a white background, without marks or imperfections. That image becomes interesting when confronted with a used, worn object, situated in a real, non-idealized context.

I’m intrigued by the meticulousness of your process, because at times you’ve even worked with microscopes, right? How do you balance such a technical aspect with the transmission of your artistic ideas?

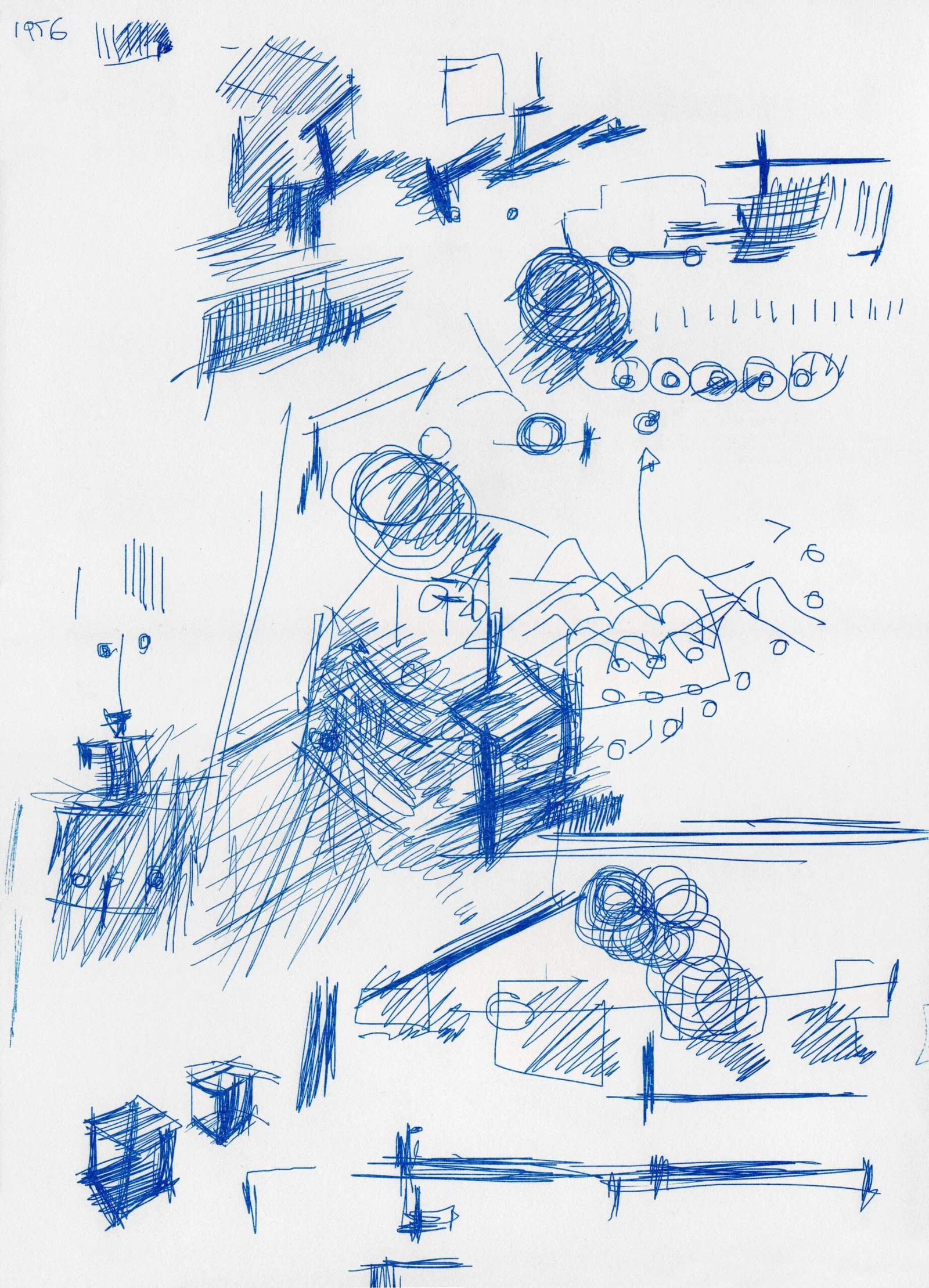

There was a key moment for me: when I was working with a microscope, trying to photograph a printed vector line. I had a very specific image in mind—a printed ink surface that, when magnified to the extreme, would resemble a mountainous topography. I didn’t achieve that image exactly, but in trying to do so I had to learn photography, video, cameras, sensors, lenses, panning systems, electric rails.

It was a full year of trial and error—buying and selling equipment, financially ruining myself (laughs)—all in pursuit of that image. Eventually, I got very close and carried it out. Since then, that’s how I work: I always start from an image I want to reach and build the entire process around it.

There is meticulousness, yes, but also a lot of fear. Sometimes I prepare so much that I end up postponing the moment of making. It’s like training endlessly for a day that never arrives. So I suppose it’s a mix of being meticulous and being a bit afraid too.

On your Instagram—especially in older posts—I’ve seen images of comics. Does this medium inspire you because of its narrative dimension?

Over time, I think that influence has faded somewhat in a direct sense, but the language remains important in my work. Not only comics, but also editorial design. When I paint, I often think of the image as if it were an editorial page. That’s where those frames or isolated forms come from.

I’ve worked in editorial design and I use very similar processes. More than comics, I was interested in manga, which I consumed heavily for years. I don’t really read it anymore, but until about five years ago it was very present in my life.

There’s also a clear influence from animation cells. In animation, each image is constructed frame by frame, and there are usually many notes—indications of color, light, texture. That helped me understand painting as a process. My paintings often function as part of a broader investigation: when I work in video, for example, there’s a set of files that accompany that research, and painting is part of that same process. Sometimes I don’t know how a painting will end. I start by painting just a fragment, and then, through readings and bibliographic sources, I add information until I feel the image closes. Even now, when I revisit some pieces, I feel the urge to keep adding layers.

I get the sense that science fiction is also close to your work, understood as a space for analyzing constructions of social possibilities. I’m seeing a book by Ursula K. Le Guin sitting on your shelf right now… [Laughter]. Could you share some of your references?

Yes. There’s another Le Guin book that isn’t here—The Dispossessed—which was especially influential for me. I don’t know if you’ve read it, but it’s a fiction built around two worlds: one capitalist, which she calls the world of property, and another anarchist.

The main character, Shevek, is a scientist who lives in the anarchist world and becomes, if I’m not mistaken, the first inhabitant of that planet to travel to the capitalist world, Urras. Through his gaze, he describes that world, which is very similar to ours, though slightly more technologically advanced. Yet the same dynamics persist: inequality, extreme poverty, opulence, nepotism, an almost aristocratic political class, a certain intellectual complacency.

There’s one passage that marked me deeply: Shevek explains that art, as we know it, did not exist—rather, it was a practice comparable to any manual or artisanal activity. Not because there was no symbolic creation, but because it was understood as a basic technique of daily life, something implicit in everyday making, not separated from the social world. That idea stayed with me. Thinking about what form art might take in a world that doesn’t even carry the memory of a capitalist past led me to question our current way of understanding it. I believe that without an economic system like the current one, art would not exist as we understand it today. The reading of the symbolic, image analysis, or even political art might transform into direct militancy, functional visual production—closer to propaganda or ritual than to the isolated space of the white cube.

In that sense, science fiction has influenced me greatly, because it allows these possibilities to be explored without having to frame them as closed proposals. Another example for me is Nausicaä of The Valley of the Wind by Hayao Miyazaki—especially the manga, more than the film. I find it extraordinarily complex, both graphically and conceptually. It anticipates debates about the relationship between nature and civilization that interest me greatly, even visually: creatures, organic forms, imagined landscapes. Beyond the plot, there’s a very powerful organic imagery that, while not literally present in my work, feels close to me.

Another very important reference—perhaps further removed from what I’ve mentioned so far—is Mary Louise Pratt and what I understood as the concept of “capitalist vanguard.” This is a very different notion from the artistic avant-garde we usually think of. It refers to a technocratic deployment driven by science and technology in the service of capital, enabling forms of domination, extractivism, and territorial control. This vanguard doesn’t only transform the land, but also the way it is observed, represented, and ultimately imagined.

Finally: where would you like your practice to evolve?

I’m running up against a clear difficulty: making video or film requires higher budgets and larger teams. The projects I have in mind demand an infrastructure that I can’t easily assume right now. I’m not talking about millions, but thousands—and a higher level of professionalization.

The images I want to produce can no longer be made with just a camera and determination; they require organization, team management, time, and resources. So I think my future desire lies in being able to grow in that sense: to build a collaborative network that allows me to develop larger-scale projects with greater ease—without giving up painting.

Interview by Victoria Álvarez Conde. 02.02.26