Lisbon-based artist Fernando Moletta welcomes us at his temporary studio at LEA Residency in Madrid, a space filled with phantasmagorical photos and hazy paintings that, as he explains, invite reflection on modernist utopias while evoking a certain melancholic liminality. We chat about this and other topics amongst the translucent presence of his foggy sculptures, where the artist even shows me the protective mask he uses to shield his face from the toxic resins he often works with. Our conversation drifts towards key themes: the importance of sustainable materialities in contemporary practice, the persistence of symbolic images within the collective imagination, and the ongoing search for beauty in an ever-evolving context.

In Architecture school, I carried out investigations on the history of modernism in architecture. My main focus was Brazilian modernists, especially brutalism. But I was always driven by a desire to understand, more deeply, what lay behind these references. There’s a curious fact: my architecture school was a polytechnic. That meant architecture was much more connected to engineering than to the arts. It wasn’t part of the humanities, but of the engineering field, even physically, because the arts were located in the city center, while architecture was housed alongside engineering in a more remote campus. The building where we studied was extremely modernist: it prioritized circulation, it was basically a large corridor divided by blocks. It was a very cold, gray, unwelcoming place. I think the architecture of the building itself shaped the way we thought about and practiced the discipline: everything was very rigorous, technical, focused on making things function perfectly and meet their objectives, without necessarily welcoming people.

This experience eventually led me down an almost opposite path: that of a critical rejection of this model. At first, it happened through research, trying to understand what kind of city these architectural and urbanistic conceptions had brought us to. The reference was always immediate: that difficult-to-inhabit building, unable to offer comfort, prioritizing function and ignoring the sensitive. Later, this critical thinking extended to cities: what is gained or lost when they are planned as blocks rather than as living spaces?

The turning point came when I did an exchange in Rome during my degree. There I studied with Francesco Careri, a professor associated with the idea of the Situationist dérive, author of a book on urban drifts. And it was in that context that I created one of my first artistic works, bringing together architecture and art. Rome — so chaotic, so unpredictable — contrasted radically with Curitiba, an organized, planned city but one lacking in encounters and surprises. This contrast marked me deeply. When I returned from the exchange, I felt a strong desire to work with art — as a way of rejecting that modernist order I came from. After graduating in architecture, I found in sculpture a field closer to three-dimensionality and the human relationship with space, concepts that had also interested me as an architect. I completed a Master’s in Sculpture at the University of Lisbon, and it was there that I developed my most recent series of works in fiberglass and resin.

And how did the most recent transition happen — incorporating painting in addition to your sculptural work?

Today I work on two fronts: painting and sculpture. They intersect, but they also oppose each other in many ways. Sculpture is very close to architecture for me, it involves drawing, planning, model-making, tests, trial and error. Moreover, there’s the question of scale, of the relationship with space and with the human body. But it is also physically exhausting work. The exhibitions I did after finishing the master’s, especially the solo sculpture show at Belas Artes, left me somewhat drained. Resin and fiberglass require strength, attention, care, endurance. Painting, which I already practiced before the master’s, became a kind of refuge and a way of bringing to another medium the themes I had been exploring in sculpture. It’s a place where

I can transpose ideas, re-signify forms, and continue my research in a way that is less physically demanding, yet still deeply connected to the same questions about space, body, time, and materiality.

Despite the fact that the formats you handle are quite different, do the themes you address relate across both disciplines?

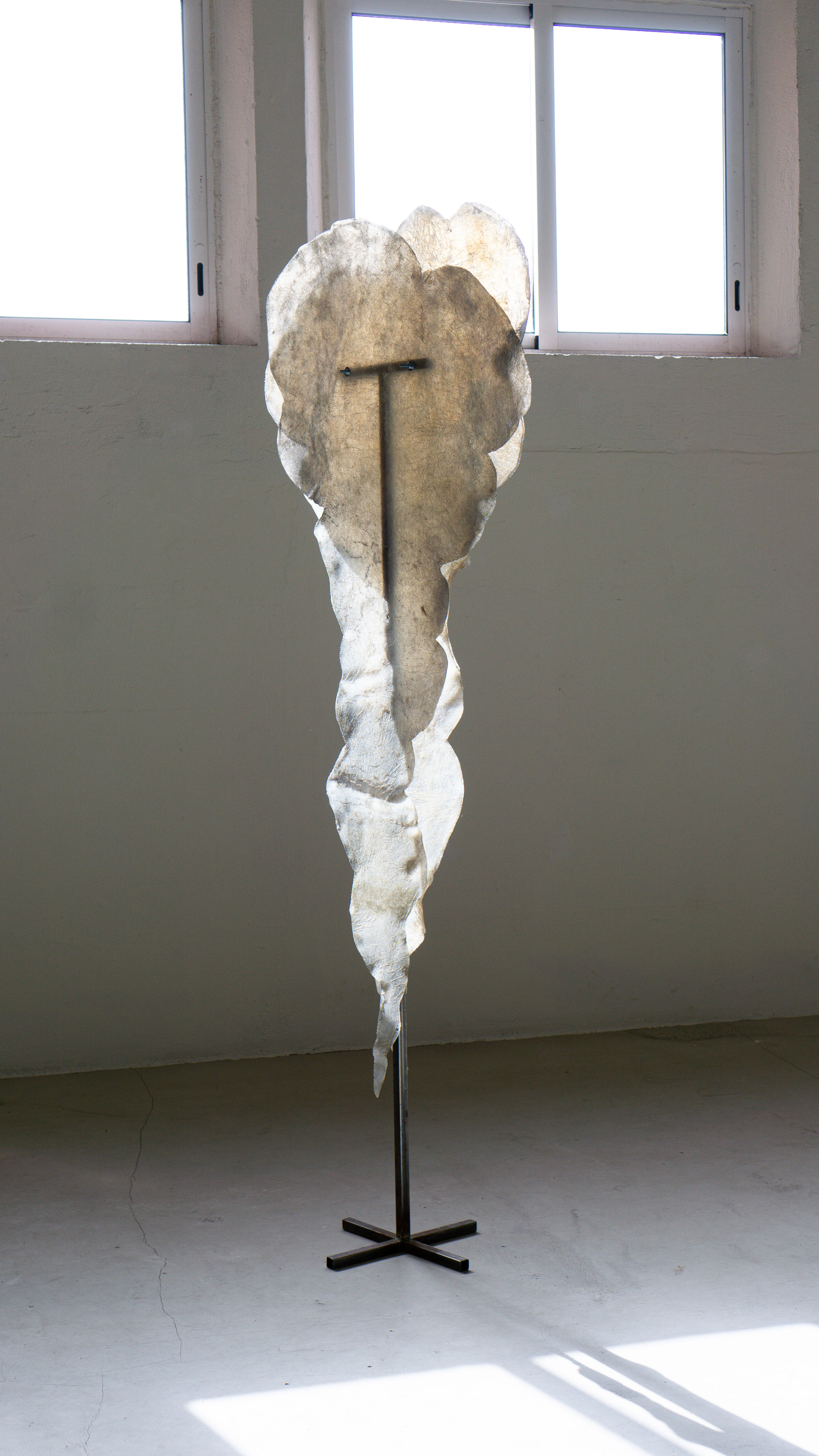

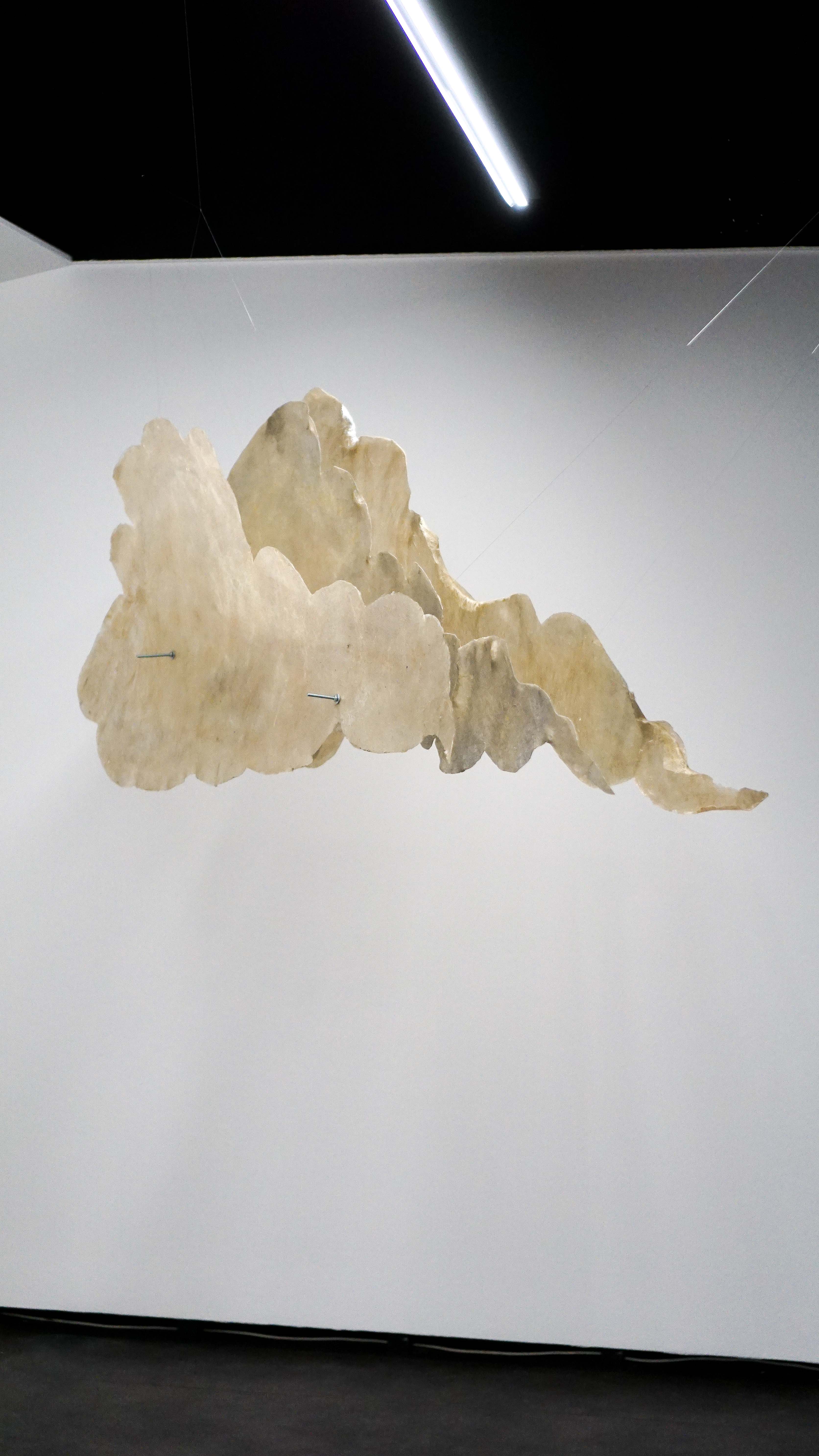

At that time, the themes of the sculptures revolved around understanding how modernity manifests today, what its burdens are in the contemporary state we live in. Since then, I have been working with three elements I chose to symbolize modernity and its echoes in the present: smoke, the ghost, and clouds. The sculptures emerged as forms that alluded to these symbols, but never literally. They are forms that move between these three elements, in an undefined, hybrid and ambiguous state. I chose fiberglass to give form to these ideas because it is an extremely industrial material, originally intended for technical and industrial uses. However, I work it manually, artisanally, leaving visible everything that is usually hidden: the exposed fiber, the resin as a structure, almost like a skeleton on display. It’s an aggressive material, but at the same time translucent — it allows light to pass through, containing this duality between solidity and transparency. This helped me materialize these symbols critically, always in a dubious, hard-to-define, almost uncertain territory.

After this intense period working with sculpture — which involved a lot of physical exhaustion and an almost project-based logic — I felt the need to explore the same themes in another medium. That’s when I returned to painting. Painting allows for a greater distance from architectural rigour. I work in a much more direct way, almost à la prima. Of course, there are layers. especially when I paint clouds, for example, but the first layer often emerges very intuitively, many times completed in a single day. The process is faster, more fluid, less technical. I give myself the freedom to distance painting from the technical rigor that accompanied me in architecture and sculpture. And I think this relates to the way I seek references: they come more from cinema than from the visual arts themselves. Cinema feeds me, in image, rhythm, atmosphere, and I end up incorporating that gaze into my painting, as a direct translation of this movement between time, matter, and phantasmagoria.

It seems like you abandoned architecture to find more freedom in sculpture, and have now transitioned to painting to find more freedom in this medium?

Yes, there’s a lot of that. I go to therapy — Lacanian — and recently I was talking about my work. I tend to talk about it a lot in therapy. And in one of those sessions, I ended up making an unexpected connection: a quote from Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love came to mind. There’s a moment when the character says he sees the past as blurred and indistinct, something he can never quite touch, but that he can somehow feel. I think that describes well the sensation I seek in my paintings: something melancholic, diffuse, almost like a smudge that carries a perception that is more sensitive than rational. This leads me back to the theme of temporality, which is where everything begins, after all. Even though many of my paintings are made quickly, in a freer, more intuitive way, the layers, the coats I add afterward, in the following days, seem to incorporate other temporalities into them. They are layers of time superimposed in the very materiality of the painting. I think this superimposition allows the gaze to perceive something that lies behind… Almost like traces of another time coexisting on the same plane.

Could you briefly summarize the project you’ve been developing here during your residency at LEA, referencing filmmaker José Val de Omar’s production?

An essential idea for me when I’m in a residency is to seek out local references, always trying to find one that resonates with my work and my research. That’s how I came across filmmaker José Val del Omar. We could say he was a surrealist and a contemporary of Buñuel, but I see him more as an experimenter, someone who developed a very unique cinematic language. I was completely captivated by the images in his films. They’re all in black and white, yet they carry a very ghostly atmosphere. He films many sculptures, some in churches, with a camera that moves very quickly. Light cuts through these images at great speed, creating an almost haunting sensation in the sculptures. He also explores the interplay between light and shadow, with quick flashes, almost like glimpses.

These images are in front of me right now, on the moodboards I prepared in the studio. In fact, it was the first thing I did when I arrived: to inhabit the space, which was completely empty, all white, with José Val del Omar’s images. That helped me find a path that connected my research to Spain, to a Spanish historiography that could dialogue with what I’ve been developing.

How did this encounter between the filmmaker’s work and your own unfold?

José Val del Omar invented something that could be considered a precursor to Dolby Digital in cinemas. The story is curious: he used two speakers, one placed at the back of the cinema and another in the front, by the screen, positioning the viewer between them. Val de Omar argued that the mix of these sounds — the past coming from behind and the future projected on the screen — was what bound the viewer to the present.

For some time now, I have been researching temporalities: what concept of temporality can we think of within art? This question of understanding what the past is, what burdens it carries into the present, and in what way this allows us to project a future is something that runs through my work very directly. Additionally, I find it significant that Val del Omar was born around 1900, at the beginning of the 20th century. His production takes shape precisely during a period marked by the Industrial Revolution, when the world was projecting itself toward an idea of human progress, moving away from a previous model and into the logic of advanced capitalism. He is embedded in that context of modernist authors, which is precisely the focus of my work.

So, would you say that you conceive the pictorial space as an abstract expansion that distances itself, in a way, from today’s wide-spread hyper realistic and photographic images?

I think so. I really like to think of the artistic field — not only painting, but art in general — as a liminal place, a territory of ambiguities. It’s not a value judgment, I deeply admire hyperrealist painting, which has its own force and relevance, but I’m particularly interested in that zone where we don’t quite know where we are. In today’s context, we live in an excess of images. If we could count how many photographs and videos we see in a single day, it would be an absurd number. And now, with artificial intelligence advancing so rapidly, we’ve reached a point where we can no longer distinguish what is real from what isn’t.

In this scenario, I believe art has the power to propose something beyond the representation of the real. It can reveal something else, an interval, a blurred space, a fissure between times. Something that is not bound to what we see, but that suggests a place between the past and the future. And this circles back to the theme of temporality, which always runs through my work: what does it mean to be delayed or ahead of reality? My aim is not to represent reality, but to explore this uncertain field, these temporal and subjective interstices that escape clarity.

A reference that came to me recently, one that is very strong for me, comes again from cinema — Tarkovsky. He made a series of Polaroids with a palette very similar to the colors I’ve been using now: specific greens and blues typical of the Polaroid process. He worked with these tones in a very striking way, including in his films. Stalker, especially, moves within that territory: a grayish green that isn’t exactly natural, almost like a contaminated green, with a turquoise inflection. I’ve been using these tones in my paintings,though these references often don’t emerge immediately, but remain in the back of the mind until they surface, unexpectedly, during the creative process.

Several contemporary thinkers consider that recurring images, which they define as “phantasmagoric,” arise at the edges of culture and reveal some kind of unresolved social trauma. I wanted to ask you: from which contemporary social trauma do you think the phantasmagoric images you produce emerge?

[Dramatic pause and laughter]

I think that… When we look at images like the landscapes of William Turner, those open fields, almost empty landscapes, it’s possible to perceive an imagination of what that place will become, that is, a project. Those landscapes carried a whole classical idea of landscape: the window, the field, the sky. Later, Van Gogh or Monet began painting train stations and steam engines. The idea of steam was motivated by the Industrial Revolution, as a world launching itself toward the future with optimism. That symbol represented, optimistically, a society preparing for industrialization, that is, for a better quality of life.

And the ghost… It’s a symbol capable of navigating between times and carrying knowledge. I think the ghost has no fixed form. It can represent itself through these iconographic ideas, because what is represented in one time will change its representation or meaning in another. But if these forms persist, it is because society has understood them differently across periods. So, imagine the idea of smoke, of the steam engine, once seen as a symbol of progress. Today, we’re much more associated with an idea of chaos, destruction, war, especially now, when we are bombarded with live images of war, in extremely dramatic moments. I also want to add something that may not make perfect sense, but that now seems meaningful to me: the European colonial idea of sculpture has always been tied to durability, resistance, value — a mentality of immortality. In other words, the modern conception of sculpture was bronze, marble, and later concrete and even steel.

Here, when working with materials that, even if resistant, convey a very different immediate impression, we have something much more precarious, almost unfinished. A form that seems as if it is still drying, not fully complete. I think we can understand that both the symbols and the ways of producing them are connected. So we’re talking about both iconography and materiality, and about how interpretations of these two fields differ across time. What can we rethink and provoke now?

I think that these questions also shed light on art as a motor of action or political expression — a topic that still sparks debate today. What kind of position do you think an artist should take in relation to these issues? Does this create any conflict for you?

I think the contemporary model that the arts face today is a very complicated and fragile place for the artist. As much as the artist is the seed of everything, relationships are now heavily based on value and sale. It’s even funny, because I was just saying that the modern idea of sculpture was linked to durability, monumentality, and value. I think today, in a way, art is returning to that modernist logic.

What happened in the meantime? Just today I arrived at a studio and people were talking about prices of artworks, about the value of artworks. And I kept thinking: have we stopped discussing, not stopped, but reduced, conversations about concepts, about how to work with certain materials, about how materials have their own agency? Everything seems to have been reduced to value and durability, to how something will hold up over time. I’ve always liked being in spaces where we can have a sense of community as artists. In my studio in Lisbon, at Duplex, we try to nurture that — and I always insist that we strengthen this sense of community. Even if it’s in a small space, in our studio, it’s important that we have debates and reflections. Because the relationship between the artist and the world is so fragile… It’s just us. And then you see that gallerists are all united, the art fairs generate huge revenues, and the artists seem increasingly isolated. Instead of creating a stronger, broader sense of community, we seem to be drifting apart.

It’s curious to talk about temporality, because this ghost of value is always returning — and in a very negative way. In the end, everything comes down to how much something costs, how much it’s worth, how much it can sell for. And artistic debate, about what art actually is, seems increasingly precarious to me.

So, do I understand correctly that your choice of materials — which are not “noble” in the sense of marble, stone, metal — is a deliberate, anti-capitalist decision?

Yes, yes. When I discovered Mark Fisher, he became a major reference for me, because he was an author very close to the themes I was dealing with. He wasn’t that distant, typical academic — he had a radio show (what today we’d call a podcast), he wrote on blogs, he was deeply connected to music. I think his overall idea was exactly that: to be close, to take part, to think from within the place of real culture. He talks a lot about how culture lost its strength to debate politics, and I think that is part of what I’ve been trying to provoke. My work with materials also speaks to that. The choice of materials is a form of questioning. Right now, for example, I’m involved in a project for my PhD, which is about biomaterials and bioplastics, bioresins, and all of this is deeply linked to the idea of resistance and value. How long will these materials last? What is the art market willing to absorb? What will be proposed?

Besides Mark Fisher, another very important text for me is Comrades of Time, by Boris Groys. He speaks about the ability of contemporary art to be a “comrade of time.” Video and performance, for example, bring this notion of instantaneous durability and community. So, I keep thinking: what can these new materials, which fall outside the usual norms of art, provoke within the system itself?

Because, in fact, we’ve reached a point where art seems to be becoming purely capitalist, an expression of highly advanced capitalism. So how can we challenge this system through other ways of making art, ways that are not conventional? Even working with sculpture and painting, which are classical media, I try to bring in new materials and an approach to painting that is very detached from traditional canons, such as priming the canvas or using tempera. I’ve never been interested in that classical idea of painting. It has always been an attempt to make painting that is almost primitive, experimental.

You have mentioned that your relationship with materials has evolved, since the use of certain toxic substances was beginning to affect your health. This, at the same time, reflects a broader social concern about certain chemicals. Are you interested in this double personal–social process?

Yes, totally. That was the main motivation for me to start thinking about new materialities. I think this connects with our discussion about micropolitics: I don’t necessarily need to think only about how the planet is suffering, I can also observe how I am suffering. Working with resin and fiberglass, whether polyester or epoxy, is extremely toxic, not only for me but also for the environment. When I started using these materials here in the studio, people became worried. The smell was very strong.

From there, I see two possible paths. The first is to think about how to keep working with these materials in a more sustainable way, less harmful to myself, which is precisely the line of my PhD research, still in its early phase, a future project on biomaterials. The second path is to embody, in myself and in the work, the impacts these materials cause on a large scale. When I look at the sculptures, this one now, but also the previous ones, I notice that they stage this current condition of things: something aggressive, toxic, rudimentary. But at the same time, what strikes me is their duality. They’re never just one thing; they oscillate, they’re ambiguous. And yet they carry a certain beauty: when light passes through the material, there’s a shock, an unexpected brightness.

This ambiguity led me to pursue what I call a “strange beauty”, a beauty that escapes the norm, that is somewhat ridiculous, out of place, or even mysterious. I remember a scene in Sorrentino’s film Parthenope. The protagonist is a muse, constantly affected by how others see her, by her conventional beauty. At one point, she meets her professor’s son, who is considered a kind of aberration by society—someone who lives reclusively because he is different, outside the standards. But that encounter reveals an unexpected beauty, a beauty she never imagined could exist. That scene marked me because it shows that beauty can arise where you least expect it, just as in art, in materials, in forms, even when they’re toxic, maladjusted, or dissonant.

You wrote a text inspired by Italian philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi: “I wanted to imagine what kind of new language we should communicate as a proposal for a new rhythm, imagining that the current one had already become perverse and useless.” Could you describe in more detail what new language you imagine?

I’ll respond with another Italian philosopher: Antonio Negri. In an interview with the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, he mentions one of his Marxist pamphleteering interventions carried out in a petrochemical factory in 1963. As a result of this action, he says that the workers announced: “tomorrow we will not work.” But that specific factory could not stop. The moment it shut down, a few hours later, it exploded. And then he describes the boom, boom, boom and says: “This is utopia.” And that image is very powerful for me—thinking about destruction, but also about gift. I’ve been thinking a lot about these two very strong words in my work. I’m always working with opposites, but these two words have been completing and crossing through my work: gift and destruction. And this idea of a factory exploding with images of smoke. And he says that this is revolution. I cannot say what we must propose or leave behind; what I’ve been trying to do is speculate about other forms.

This idea of speculation is also very interesting to me. I think proposing can be very presumptuous, but speculating about new alternatives is also part of provoking. I think I always like to work with that as well—speculation and provocation. Will what the viewer sees disturb them? Will they find it beautiful? Strange? What will they take away from these images that I construct and materialize? Because I’m not very interested in them finding it beautiful. That has never interested me. But I am interested in them feeling provoked, unsettled, even disturbed or haunted. Because “haunted” is also a very compelling idea, as it is something you carry with you. To be haunted is also to carry, through time, an idea that marked you deeply—meaning, it haunted you.

I find your work is very conceptual, in a sense, while art is often associated—topically at least—with a more emotional reaction. I wonder how you negotiate these two ways of approaching art: a very intellectual path and a more emotional one. Is that something you somehow struggle with?

I think so, and it’s good that it’s so. I think lately I’ve been able to negotiate these two aspects better, mainly through the idea of this search for strange beauty. Because I also have this academic side—I did a master’s degree, then worked at the School of Fine Arts as a researcher, and now the PhD is a research project, a very academic work. One might think these things are in very opposite places, but I’ve been trying more and more to make them co-participate. In writing articles, in the academic work, I’ve been thinking about writing in ways that are not those imposed by the social sciences, the rules of academicism. I’ve been trying to understand how art can write in a different way as well, meaning: how to develop a theoretical-practical work. How writing can also be poetic, how it can provoke questions, within the limits that are imposed, of course.

I think that in artistic work there are also limits that are imposed. Especially when I think that I know the state of things, but I also want to sell — after all, I need to survive. This work is not done only for itself; we discussed that it’s also important for it to circulate in ways that finance future works.

This was always difficult for me because I always wanted to make a more experimental work, more oriented toward this idea of provocation. I think it always had that, which limits how it circulates. I think the work is much more spatial and embraces that condition better than something meant for wider generality. And then, when I began to grasp this idea of strange beauty, I also saw a way of understanding the relationship between art and visual arts as a liberation from those barriers, but also an acceptance that art has its own barriers. It would be naïve to think it’s a space without norms.

You’ve mentioned cinema several times as an influence. Could you tell us about other directors who have especially impacted you?

There’s something fundamental in my life: during my exchange year in Rome, I discovered Pasolini. That was a great revelation for me. There’s a personal detail I rarely explore in my work, perhaps because of matters I haven’t yet resolved in myself—but I was born in a small town in the interior of Paraná, a state in Brazil. Not in the capital, but in a small town of about ten thousand inhabitants.

Growing up gay in a place where technology arrived very late shaped many things in me. What references did I have? My way of escaping was to look for others, driven by a sense of urgency. My relationship with technology has always been curious because when I talk to people slightly older—five years older—we end up having almost the same references, like MSN or the first online games. In my town, these things came late. What was contemporary for me was no longer contemporary for those living in places with faster access to technology. I got the internet at home late and all that. When I discovered Pasolini, it was a real revelation because he seemed like someone of a very particular kind. Today I think he would be both very loved and very hated, because we live in a time when we try to limit ourselves to be accepted by more people. Pasolini was deeply contestatory, not concerned with being loved by everyone, but with sustaining the opinions he truly believed in.

Pasolini’s cinema and poetry influenced me a lot to the point where I began carrying poetry in my life from the moment I encountered him. He is fundamental, even if his influence isn’t very visible in my work. Visually, Andrei Tarkovsky is unavoidable, especially Stalker, which I consider very nebulous—the idea that you can’t quite perceive what time you’re in. It’s almost a linear space without time. The colors I use also come very much from Tarkovsky’s cinema. Recently, Val del Omar has also become an important reference, though more recent for me. In the end, there’s a lot. I am very attached to film citations. Most references don’t directly influence how I formalize the work, but they impact an earlier process, the conception of the idea, the way it emerges.

You’ve already talked about the influence that living in Rome had on you. What about Lisbon?

I arrived in Lisbon just a little before the pandemic hit, about a week before everything shut down. I experienced Lisbon in a very closed way, in that very specific situation where we were all confined. For a long time, Lisbon was my home, my room, my daily routine. Gradually, as things opened, I began to understand the city. And something I’m very grateful for was finding Duplex, which gave me a sense of community in a place where I still didn’t know many people. Once again, I emphasize the importance of these community spaces artists can create together. I made friends there—people I still carry with me today. From there, I began to truly get to know Lisbon, and I think it is very close to Rome. Rome is the city of seven hills, and Lisbon also has this very rugged topography, maybe even more so. Currently, I live between Portugal and Brazil. I recently spent nine months in Brazil, after spending a long period in Portugal. So, after a long time away, I spent a long time back in Brazil.

It’s a very different relationship from city to city. Lisbon demands a physical effort that takes you to different places, it’s a much more tactile city, a more bodily, intense relationship. It has a very present human warmth, thinking even of sweat, of climbing hills and ending up drenched. The Lisbon summer is always striking. Curitiba, on the other hand, is a very neutral city, I’d say—one that doesn’t offer many emotions to experience. I don’t mean that in a negative way; I really like Curitiba. Even though I was born in the countryside, I spent most of my life there, so I consider myself very much from that city. Lisbon is now a new home. And I think that says a lot about my story and my work: living between these two cities.

Curitiba is a very planned city. In the 1990s, it became known as an ecological, innovative city. The public transport system has always been praised for being cheap and efficient. Lisbon is the opposite: it resembles Rome, with this idea of chaos, of a city that was totally destroyed by an earthquake. That open wound, that destruction, is still very present in the life of the city, the tension that there may be another quake, another shock. Lisbon is very effervescent, very alive, unlike Curitiba, which is more neutral. I think this also reflects how my work is constructed. I live between these thresholds. I always say my work speaks of oppositions — and I realize that, in fact, I also live between oppositions.

What about your residency here at LEA? Can you tell us about your experience?

There was a sentence I heard in the first week, spoken in Spanish, but I’ll reproduce it here in Portuguese: “Todas as histórias de amor são histórias de fantasmas.” (“All love stories are ghost stories.”) It’s the title of the biography of American author David Foster Wallace. And the phrase came up without much context, as something loose that I simply grabbed. It stayed in my mind the entire residency — now, nearing the end, this idea that all love stories are ghost stories led me to think about the opposite question: what are love stories?

José Val del Omar has a quote in one of his films that I’ll try to reproduce in Spanish, but I hope it’s understood: “La muerte es solo una palabra que queda atrás cuando se ama. El que ama arde, y el que arde vuela allí, a la velocidad de la luz, porque amar es ser lo que se ama.” And I think I spent a month reflecting on this. Madrid is a very… sensual city. Spanish is also a very sensual language. Even though I don’t talk much about love in my work, there is this idea that cinema, which comes from behind, is still a component that deeply motivates me. It’s something that crosses all our relationships and the way we connect with people.

Aside from the interaction with artists here and the studio work, I spent a month very much alone, very focused on producing. But at the same time, there was this echo of the city’s liveliness, people on the streets until midnight, always ready to celebrate. So, during this month, I lived a very intense duality between the professional and the personal. This idea of ghost stories, of love stories, kept me in that duality. But it was a very positive month. I worked a lot. I think residencies are also great for strengthening relationships with others. I’m very grateful that you accepted being in contact and collaborating, because being in a residency means being in an unusual place. You need to be open and ready for people to intervene in your space — and that is very enriching.

And, finally, dreams or future plans?

Lately I’ve been very focused on the PhD, which is a practice-based theoretical PhD. It includes a partnership with Técnico de Lisboa, and my co-advisor is from chemical engineering. The idea is precisely to inhabit an engineering laboratory in order to think about art. That has made me worried, tormented, but also very excited.

I’ve always enjoyed reflecting on this place of art that can inhabit other spaces that are not properly its own. Thinking about how scientists and artists can collaborate is something that motivates me a lot—these interdisciplinary collaborations have been a great stimulus. My plan is to start researching the idea of producing bioresins and bioplastics. This has been deeply inspiring, especially because these materials can generate biopigments and open new possibilities for thinking about painting, from pigments that are not necessarily oil-based. I’m also interested in continuing this provocation of moving away from the historiographic place of resistance, value, and durability, to think about new materialities, what lifespan they might have, what it means, for art history, to have a sculpture that may or may not degrade. Or even the challenge of creating a biomaterial that doesn’t degrade. This has been my great motivation for the coming years.

Interview by Victoria Álvarez Conde. 07.01.26