I meet Madrid-based artist Mar Cubero at her home-studio in Puerta del Ángel, a mix between a Nordic-style design shop and an old carpenter’s workshop. Everything is freshly renovated and spotless, neatly arranged like a Rubik’s cube: iron shelves full of materials she works with (mostly wood, paper, and all kinds of dyes), rolled-up papers, and sculptures and drawings in progress hanging on the wall. A blood-red door cuts through the room like a flash of light.

I first came across the sculptor’s work at her solo show at Picnic gallery in January of this year. From the very beginning, I was drawn to the mysterious calm of her abstract sculptures; the sense that something is hidden within those meticulous and lightweight forms, crafted with organic materials, strangely cold and yet at the same time welcoming. Seeing them live in the studio radically changes the whole picture. The best part is when Mar assembles the works before my eyes, as if by magic, starting from a small wooden base and a hand gesture that transforms a sheet of paper on the table into a three-dimensional sculpture. The artist invites me to touch the dyed papers, to walk on them, and tells me she does it herself—she likes to infuse her work with the traces and imperfections that come from working directly with matter. On the edge of her table, hidden under the surface, there are photos glued of columns, watering troughs, puddles, and architectural structures in unsettling tension, on the verge of collapse. Her work is a matter of contrasts: with her soft, almost childlike voice, she tells me about working from discomfort, from obsession and fragility, and about one day achieving her ultimate goal—to defeat gravity.

During the interview, she keeps repeating that words are not her thing, that she works better with images, and maybe that’s true. But reading her answers is amazing, and here is what remains of our conversation:

Hi Mar! I feel like the base of your work lies in materials, especially wood and paper. What first drew you to these mediums, and how has your relationship with them evolved over time?

I started working with wood because it was accessible: I could buy it and cut it myself. Now, looking back, I see I couldn’t have chosen anything else. Wood is a living material; it changes, mutates, and transforms depending on the circumstances. Take humidity, for example: a table doesn’t measure the same in Madrid as in Galicia. That ability to transform fascinates me. It’s also a material loaded with symbolism. It’s both primitive and domestic at the same time. It has something that connects us to the essential, to what existed before everything became complex. It carries a silent memory that contains stories we don’t see, but that pulse beneath the surface.

There’s also a personal link: my grandfather and his family were cabinetmakers. I never saw him work, but I grew up surrounded by his furniture and later inherited some of his tools. Many of them I keep as relics, even if they have no economic value. I suppose by choosing wood, I was also seeking something familiar, a material that could teach me.

Paper, on the other hand, came out of necessity. When I left my job, I couldn’t afford expensive materials. I started working on small formats, which frustrated me, because what I really wanted was to work with volume and space, but all I found were limitations. Until one day I thought: “How can I create volume with paper? If that’s what I want to do, I’ll have to find a way.” I tried folding it, crumpling it, and letting it speak from its own possibilities. What began as a restriction turned into a discovery.

When a new project begins, where does it usually come from? An image, an intuition, an idea...?

I don’t work from closed projects, but from obsessions. Sometimes it begins with an image, a place, or something I come across. I usually don’t realize something has become an obsession until suddenly I notice I’ve collected tons of images around it. I don’t work directly from images, but like everyone else, I consume a lot of them. I have a massive archive of screenshots, things I see on Instagram, online, or photos I take on the street... When I look through that archive, I discover repetitions: staircases, rooftops, airplanes, ruins, columns, broken pieces. Also traces: the presence of the body on different surfaces. Once, at the beach, I stayed sitting in one spot for so long that my silhouette was perfectly imprinted in the sand, full of detail. It made me laugh. Small anecdotes like that interest me.

When something repeats, I think: “There must be something here. Let’s see what it is.” Sometimes nothing comes of it. But other times I get stuck on it and can’t work on anything else, even if I want to. I guess my work has always had to do with structures, anchors, constructions... even if I didn’t think of it that way at first. So, where do projects come from? From there: from an obsession that grips me until I work it out.

More specifically, where did the main sculpture in your solo show Cuando el Invierno Cae (2025) at Picnic gallery come from?

More specifically, where did the main sculpture in your solo show Cuando el Invierno Cae (2025) at Picnic gallery come from?The sculpture shown at Picnic came from an image. As I mentioned, I get hooked on certain things and work from there. At the moment, three images/ideas are with me. One of them emerged during the workshop counter-archiving-practices led by Miranda Pennell as part of the Instituto de Prácticas Artísticas (JAI) summer program. She made us dig through a specific archive at Tabakalera, and there I came across a series of photos of an old scaffold collapsing. It was five or six images showing it coming down, and people reacting. I became obsessed.

Later, by chance, when I was back in Madrid—searching online or just browsing—I came across another image. Miralles had been building a sports center in Huesca, and from one day to the next, the entire roof collapsed. It was in the news: “The collapsed roof by Miralles.” It was under construction, and the whole thing came down. In my head I thought: “It’s the same thing!” The Picnic piece comes from that—from those scaffolds and huge structures that shouldn’t fall… but do.

You mentioned three obsessions… Aside from the one you just described, what are the other two?

On one hand, water troughs. One day I realized my phone was full of photos of troughs and puddles—objects that hold water, that are empty, that are hollow. One of the works in the Picnic show also came from that idea of containment.

The other image that’s stayed with me for a long time is the columns in Rome. The city is full of ruins, and I’m struck by how many are pierced with iron structures. These small supports fascinate me. They’re made so the columns won’t fall, so they won’t collapse. I find them beautiful, almost like crowns, incredibly delicate… but also violent, because they pierce the columns with these metals, these scaffoldings. They exist right at the edge between delicate and aggressive, fragile and structural. They make me wonder: how is it possible for a column to collapse, if columns are meant to hold things up?

You’ve also spoken about a “fight against gravity” in your suspended pieces. Where does your interest in this tension come from?

It’s connected to the idea of falling, of lightness and fragility. Also to the concept of error. Things fall because something fails. A scaffold objectively shouldn’t collapse. If it does, it’s because there was a mistake. Miralles’ roof wasn’t supposed to collapse. It’s that failure… As long as nothing goes wrong, you don’t notice; everything just works. But when something breaks—or threatens to—that’s where I want to look. I’m drawn to things that are about to fall but don’t. Or things that seem about to break but remain whole. It’s tied to fragility, to the impossible.

It’s also about weight. Sometimes I make pieces that look heavy but aren’t, and others that are truly heavy but appear light. I enjoy that physical play with weight.

Seeing your work at Picnic, I sensed a tension between a certain aesthetic coldness and an intimate, almost domestic atmosphere, like a cabin. It struck me as an interesting contrast between cold and cozy, impersonal and familiar. What are your thoughts on this?

I agree with that reading. It’s something I don’t fully understand yet or know what to do with. I linger a lot in that tension between opposites: delicate yet resistant, fragile yet powerful. It feels like a constant pulse. I sense it, I perceive it, I recognize it, but I can’t always explain it.

At the same time, it surprises me, because I use warm materials: natural woods, fabrics, papers... Everything should feel cozy. But sometimes there’s a sense of coldness or distance. I suppose that has to do with me: there are aspects of my work I don’t yet feel comfortable verbalizing, but they’re there, latent. So, a connection can emerge… or not.

There’s also something about exposure. Not so much in the pieces themselves, but in what it means to show yourself as a person. It’s like opening the door to your home for everyone else. Sometimes I develop strategies to protect myself, to keep it from being too obvious, to maintain some distance—because even if my work isn’t autobiographical, there’s a lot of me in it. And it’s hard to separate that.

Poet María Gómez Lara read one of her poems at the closing of your show at picnic, exploring themes related to fragility. What connection do you see between that text and your work?

That theme connects directly to a recent personal experience. Just over a year ago, I had a serious accident right here, in this space. It left me bedridden for quite a while, with a slow, heavy recovery. In some way, I’m still in that process. And everything ties together, because I’ve always been aware of fragility in my work—of what seems strong but isn’t, of emptiness, of vulnerability, of the body. These were things I was interested in before, but not with the same intensity as over the past year. Now I’m not only aware they exist—I’ve started to speak about them, because they directly concern me.

Before, when talking about my work, I would retreat into technicalities, into the properties of materials. But after the accident, I couldn’t hide there anymore.

The show was curated by Jairo Antonio Hoyos. When I told him in detail what had happened, he quickly connected with María Gómez Lara—he knows her personally—and said: “You have to read this collection of poems.” He recommended it to me as something that could give words to what I was going through. And it did: that book cut straight through me. It was like reading someone who, with precision and beauty, could put into words something I couldn’t articulate.

That’s why the most natural—no, the most necessary—thing was to borrow those words for the title of the show. María was amazing: she let me use her words and also agreed to read her poems at the closing. For me, it was a way of thanking her—by inviting her into a space that wasn’t hers and letting her voice inhabit it.

That collaboration also opened me up to the idea that, if I can’t do something, someone else can. Collaboration can be incredible. I didn’t do it before. And that’s been a professional learning too: if I can’t find the words, maybe someone else can. And maybe they can also receive something from me.

How does working on very small pieces compare to large-scale ones, like the Picnic installation? How does your relationship with the piece change depending on size?

For me, it has a lot to do with the body. I think the space things occupy is crucial. I don’t mind working big or small, but always through corporeality, through how that object is inhabited.

Some small pieces take up a lot of space, and some large ones don’t. I like to observe that. I play with this a lot in the studio: how much space something occupies, how much weight it has, how much presence. Sometimes I make small pieces to test how far they can go, what intensity they can hold. Other times I make large pieces because I need to inhabit them, surround them, see them from different angles.

For the large Picnic installation, it was essential that it could be walked through, circled, seen from above and below. That it would block passage and at the same time force you to move. Being aware of the space things take up, of how they interact with the body that looks at them, matters to me a lot.

You’ve also mentioned the importance of materials adapting to your body, to your own scale. Can you tell me more about that?

Space is fundamental for me—not just as an artist but as a person. It deeply affects me; I need to feel comfortable. At first, in this studio, I struggled a lot: it took me two or three years to really feel it was mine. Once I did, that small space became my place in the world.

Because it was so tiny, I became very aware of how much I myself occupied it. That also dictated how I stored my works: everything had to be transportable by me. Not only because the space demanded it, but because I’m terrible at asking for help. I need to be able to move everything on my own. Now my studio is a bit bigger, but even so, the works either come apart or I can carry them myself. They have to be at my scale, possible for me.

In that sense, another question I have is: how site-specific do you consider your work? Do you need to respond to a specific space to produce a piece, or do you think your works can adapt to different places, even without visiting them?

I think I need to know the space. I spend so much time in my studio that most of my pieces end up adapting to whatever space I have at the moment. When I had very little space, the pieces were smaller, because I didn’t have the option to work larger. As I said before, I care a lot about the physical sensation a work produces, and if there’s no room, I have to explore that through smaller scales. As my studio has grown, so have my works.

Everything relates back to the studio, whatever it is. But also to the space I’m working for—details like a corner, a niche… For example, in a group show at Espacio Valverde, there was this awkward corner in the gallery, and my piece ended up there. I hadn’t conceived it specifically for that spot, but I had thought of it in a corner of my studio. When I arrived at the gallery, I thought: “It has to be in a corner.” And I found that overlooked spot.

So, was it determined by the gallery’s specific space, or by the fact that I’d made it in a corner? Probably the latter.

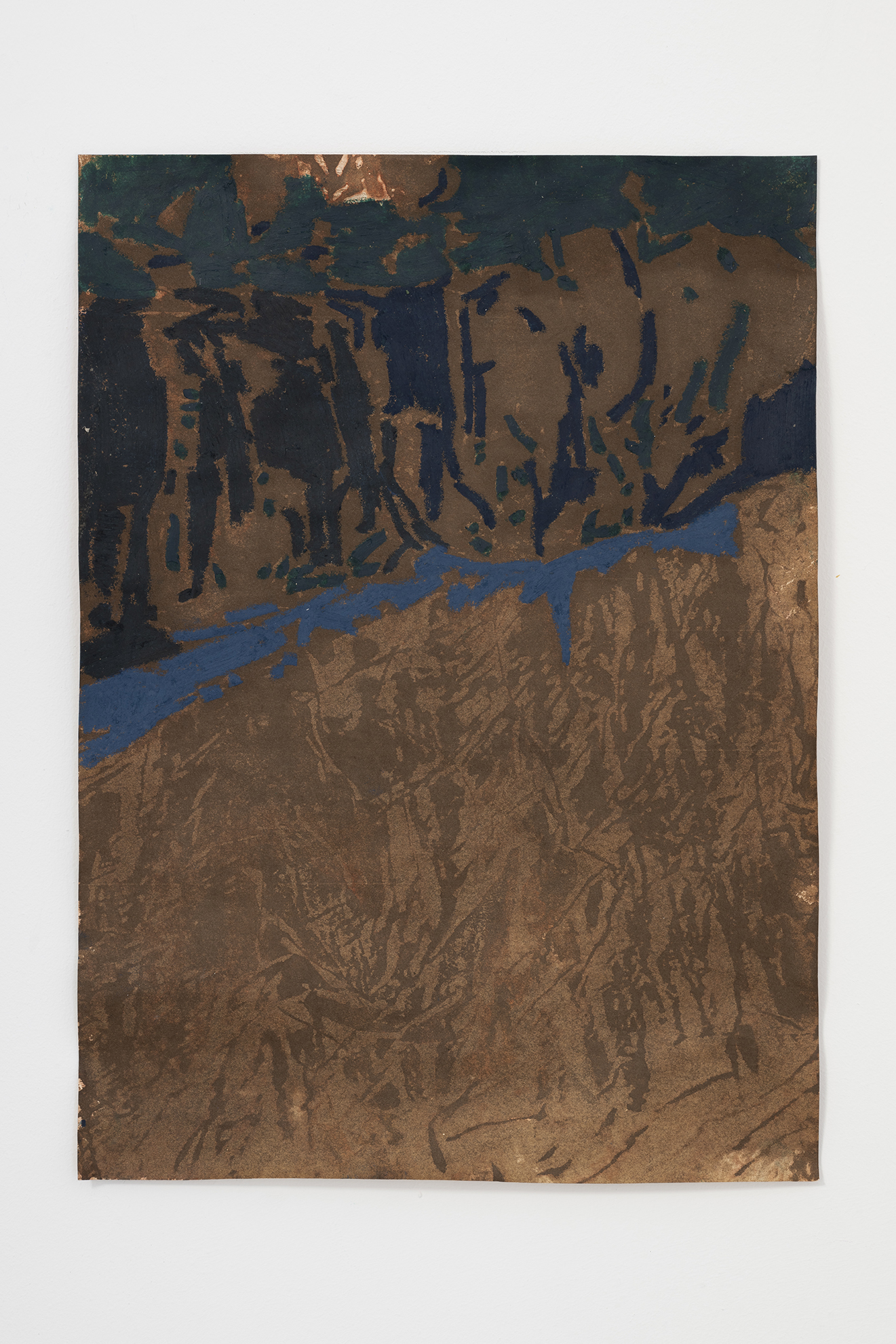

I’ve seen some of your oil works, and I’m curious: how do they differ from your sculptural practice?

What I use are oil sticks, but I don’t paint with oil. I don’t want to paint. Painting intimidates me a lot, so I don’t use brushes. What I do is closer to drawing, to gesture, to the body. I work with waxes and oil sticks, yes, but I don’t paint—I draw.

I get obsessed with categories, with setting boundaries for myself. I think something similar happened with paper. At first, I didn’t dare to say I was making sculpture because I was working only with paper. So I set myself the challenge of letting those papers become sculptures, without intervening too much. I look for paths along the margins, more complex solutions for things that could be resolved easily, but that I don’t want to solve in an obvious way. I like the work to have its own logic.

Earlier you mentioned you like to surround yourself in the studio with elements that make you uncomfortable. I find that process fascinating, and in a way it connects with your interest in things that aren’t what they’re supposed to be—like the fallen scaffold or the column that doesn’t hold… Do you work from “the other side” of things?

This hasn’t been the case for very long, but yes, it’s true. A couple of years ago I realized I was bored with my own work. I felt blocked, or maybe stuck, like I was doing the same thing over and over. One strategy I came up with was to surround myself with materials I didn’t like at all, that made me uncomfortable, to see if that would trigger something in me. And I realized it did: there’s a visceral rejection, and that rejection forces me to act, to do something so that the uncomfortable presence goes away or simply transforms.

For example, before the water trough series, I started putting objects I didn’t like inside them. That forced me to flip things around, modify, add, subtract… Those uncomfortable materials gave me an excuse to think and rethink. It’s just another work strategy. What unsettles me, what disturbs me, is exactly what sparks my desire to produce. I guess that’s why I turn to it: because from the very beginning, that’s what sets me in motion.

It also has to do with the way I relate to the world—through doubt. I’m constantly questioning everything. Putting myself on the uncomfortable side is a way of questioning myself, of staying alert. The only thing I know about the world is that I have no idea about the world. With art it’s the same: the only thing I can say is that I have no idea. So I look for those things that unsettle me or generate doubts, because they force me to try to understand something. Even if the findings are small, they give me little certainties that allow me to keep going.

Along these lines, can you tell us about specific references that inspire you?

My biggest influences are the people around me: my friends, everyday conversations, the music I listen to, or a film we share. At this moment I don’t need to turn to big names to feel addressed—the nourishment comes from my immediate context, from what surrounds me and crosses through me every day.

Of course, there are artists and readings I admire, but over time I’ve discovered that what moves me most are the small, unexpected things: a poem stumbled upon by chance, a line in a novel, or a gesture on the street. I also make a conscious effort to look at the work of other women artists; I’m interested not only in what they produce but in their determination to sustain themselves in this profession. That commitment, that tenacity, are my true references. Because in the end, what inspires me most is seeing someone insist on creating, despite everything.

You mentioned that when you step on your work, you let that trace remain in the piece. Are you interested in your work conveying a sense of having been lived in, walked through, even worn down?

There are many layers here. Some have always been present, others have grown stronger over time. For me, it’s always been essential to respect the material, whatever it is. If something scratches, breaks, if an error or an unexpected mark appears… that becomes part of the piece, part of how I’ve related to it. Sometimes I work with techniques I don’t master. I don’t know how to sew, for instance, but if I want to join papers without glue, I sew them. And of course, knots form, the thread breaks… but that accident gets integrated into the work. I don’t hide it.

I think my work has something of skin—marks that speak of time and of what’s been lived. I’m interested in pieces preserving that memory: that it’s visible they’ve been inhabited, traversed, that they have fissures. In the Picnic exhibition, for example, I loved how the light filtering through the doors slipped into small openings in the large installation, turning fragility into part of the experience. A seemingly solid surface full of pores… like skin: resistant and yet vulnerable.

I don’t know if my work has helped me process personal experiences, or if it already spoke of these things and, over time, I’ve simply learned to recognize them more clearly. What I do know is that my practice has always been linked to this idea of trace, of material record, of letting what happens—even the unforeseen—remain and converse with the rest.

I was surprised that, when I arrived at your studio, you invited me to touch the pieces. At the exhibition, that didn’t seem to be your main goal. What kind of relationship would you like the audience to establish with your work?

I love it when people touch my work. A lot. Even though I completely understand why it’s not possible in an exhibition space, I still like to imagine that possibility.

It has to do with time. My work is slow—both in how it’s produced and in how I like it to be experienced. I’d love for people to spend time with the pieces. I don’t want to tell them anything explicitly, but I do want to provoke questions. For that, exploration is key. Sight gives you specific information, but if you can touch, smell, or even walk on the work, everything changes.

One of the things I loved most about the Picnic show was when the doors opened and a draft of air would come through. The piece, very light, would move. I loved watching people’s reactions: first fear—“It’s going to break!”—and then surprise, when it didn’t. That sparked curiosity, which led to the desire to touch it. Some people did, and I thought it was beautiful: they had stayed long enough for that desire to appear. That’s why I enjoy studio visits: you can tell someone, “Build the piece yourself, make it yourself.” My work has a lot of play in it. I play a lot here and have fun, so if someone else can experience that, I find it incredible.

Looking ahead… Do you have any dream or path you imagine for your practice in the long term?

Honestly, I don’t have a clear plan. My wish is simply to keep making, to keep moving. And that already feels like a lot. There’s no grand ambition: I’d love to just remain here, in this small Madrid studio, making things, contemplating, reflecting… and repeating that I don’t paint because I don’t use a brush [laughs]. That’s the future I want: to sustain this over time and keep going. Hopefully more will come, of course, but even that alone would be enough. It might seem like a small thing, but I think there’s nothing more ambitious or radical than being able to continue.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 03.09.2025