A table says a lot about someone… Tere’s? It’s a wild mix. Letters from Interviú, haberdashery tags, an air freshener with a killer logo, and her latest works-in-progress: sculptures made from underwear and a disposable camera wrapper stuffed with half-chewed gum.

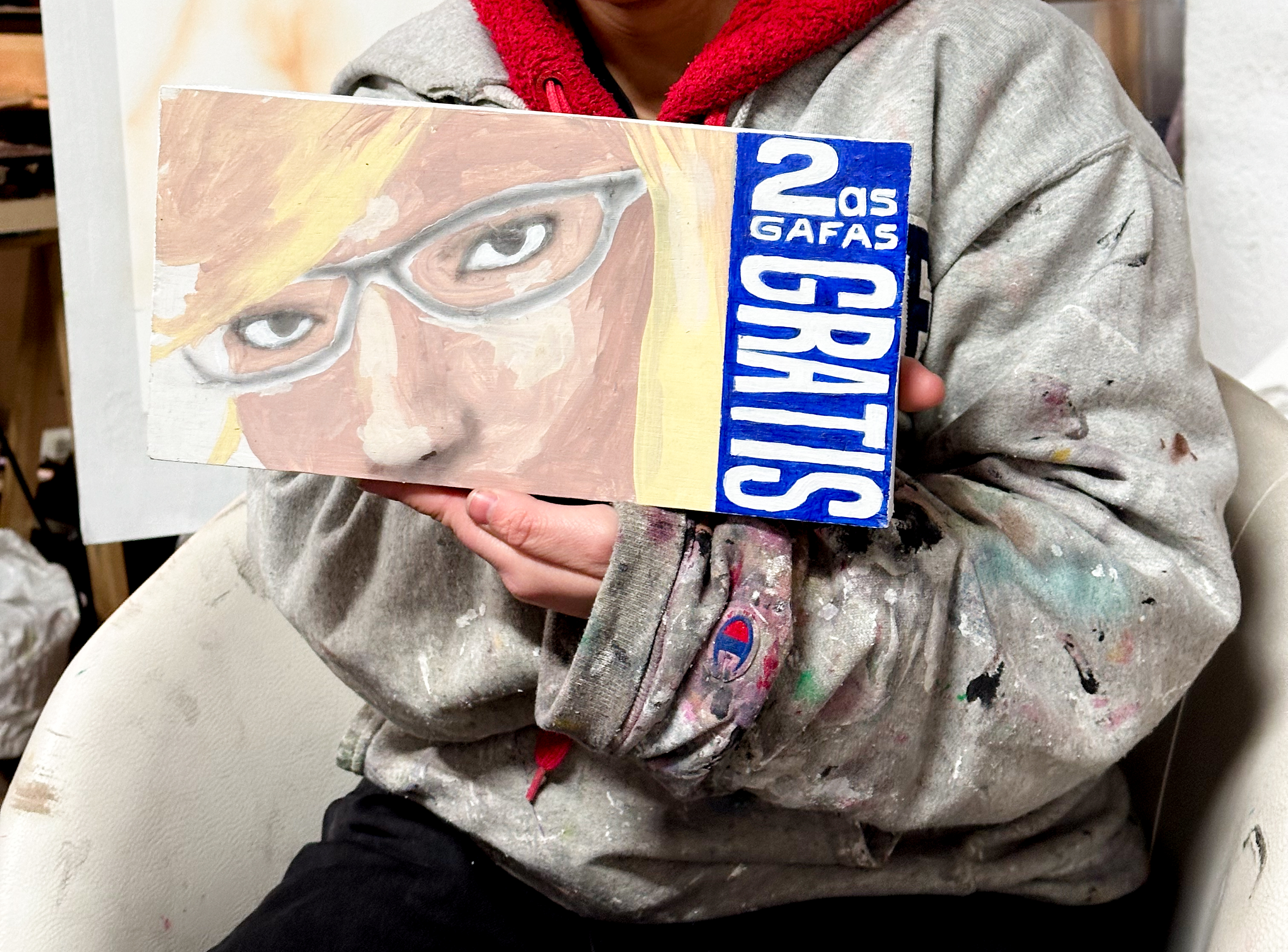

"I'm a huge fan of trash," she tells me with a giant grin at her shared studio in Casa Antillón. Since graduating in Fine Arts from the UCM University in Madrid, she’s been hopping from one technique to another, something she describes as happening in “spurts.” But certain elements keep sneaking back into her work, always wrapped in the same pastel-pink color palette. Mannequin-like girls with a striking resemblance to fallen icons of the '60s, a chaotic mix of both Spanish and international advertising references, all mashed up with garbage and a grunge-y edge brought to life by her ever-rebellious airbrush textures. There’s also a slightly naïve vibe: Pucca popping up between pin-up girls and mugs decorated with boobs and cityscapes. Irony? I don’t think so.

Tere admits she sometimes has no idea what she’s doing, that whenever she tries to plan things, she messes up, and that her best work happens when she just follows her gut. Thankfully, I recorded this interview, so hopefully, some of her wild energy made it through. Because, as a mutual friend once put it, “In the end, Tere has that scruffy hippie thing where she just loves to chat.” Here’s an extract from our talk:

Well, once again, I’ve had a “spurt”—that’s what I call these impulses that take over me. When I first started painting, I was more focused on the image itself, but over time, I became interested in textures and started experimenting more abstractly. That abstraction also carried over to the materials I used.

I've always been interested in objects, but before, it was more in a representative way, like capturing them in a painting. My work evolved progressively. I started feeling the need to add elements or shift the focus beyond just the painting. Like, I’d put nails on the frames, and I realized how those little add-ons affected the piece, and I found that super interesting. Bit by bit, I became more drawn to those details, and now, suddenly, I enjoy working more with the object itself.

Now, when I paint, I love mixing textures and discovering new things within the piece. As a viewer, I adore paintings that make you stop and really look, where it seems like the artist drove themselves crazy over something that appears simple but has multiple layers of meaning. I also like putting myself in the viewer’s shoes when I think about my own work, and I love playing with symbols and the hierarchy of elements within a piece.

I quickly get fed up with what I did just three months ago. I think that has to do with the way we consume things nowadays. Even my own stuff, I get tired of it fast. But in general, I love contrasts, and this constant rejection of what I did yesterday forces me to seek them out in an organic way. Not just contrast for the sake of it, but how contrast can become a conversation—a dialogue—and how we engage with that dialogue. That’s why I’m really enjoying working with objects and materials now. Everything has to be in conversation: textures, colors, even the casings and what they contain.

After your Erasmus at the Albertina Academy in Turin, you pursued a Master’s in Fashion Design and Direction at IADE. How does that phase of your life reflect in your current work?

After your Erasmus at the Albertina Academy in Turin, you pursued a Master’s in Fashion Design and Direction at IADE. How does that phase of your life reflect in your current work?

During Erasmus, I went through some really defining experiences and met people who completely changed how I see aesthetics and even how I understand the world. I guess moving to a new city does that to you.

On the other hand, the Master’s helped me dive deep into image theory, visual theory... The study of fashion, for me, was a revelation, especially in how society interacts with images and bodies and what that actually means. Like, image as a symptom.

During that course, I also developed a magazine called Turista, through which i first explored irony and appropriation. I was really into the idea of observing from the outside, of decontextualizing things. I think nowadays, we have a very tourist-like gaze—we observe things from a distance, take objects or images out of context, and there’s an irony that comes with that. That project was kind of the theoretical foundation of what I do now. That’s why I find it interesting to use junk, found objects, or ad images—it’s an act of re-signification from the very birth of the piece.

Coming from illustrating comics, are you still interested in a narrative dimension in your current work? Are the figures in your paintings conceived as characters?

Coming from illustrating comics, are you still interested in a narrative dimension in your current work? Are the figures in your paintings conceived as characters?At the time, I was making experimental comics. I played a lot with the speed of the drawings to control the rhythm of the story or used symbols like hieroglyphs as a narrative axis. It was more of a game of pacing. I feel like that’s faded away a bit, but I guess some traces remain—a foundation or a kind of storytelling that runs through my work.

Since then, I’ve used characters as building blocks for other ideas. In the artist residency I did at Casa Antillón—before it became my workspace—the whole project revolved around a teddy bear called Teddy Beer, which was the corporate mascot of a beer brand. The installation was set up so that when you walked in, you entered his living room and found a giant teddy bear, dead on the couch.

In my paintings, I’ve used characters to varying degrees. The pink-haired girl, for example, is a calendar girl. I painted one piece where she’s in front of a calendar, and then another where she’s missing a leg, standing in the same scene. I was looking for a sense of continuity that made the character feel real.

Then there’s Chica Tigre, a project I never finished or published. It started with a girl with her face painted like a tiger. I loved the first painting of her, and from there, I started giving her more traits with the help of friends in the studio. It became this super collaborative thing. Each time we talked about her, new layers kept emerging. Eventually, she turned into a Marilyn Monroe-type figure, but even more romantic—she even released records and everything. Then, I made a video with my mom dressed as her, imagining that she was one of those famous people who vanish from the spotlight, and no one knows what happened to them until years later. It was all about constructing an image of a woman, piece by piece.

For a while, I painted a lot of women. They all had this slightly unsettling beauty—super conventionally attractive, but with something that threw you off. I wasn’t necessarily aiming for that, but I found it interesting to explore from that angle.

When dealing with provocative femenine imagery, are you intentionally exploring themes like the sexualization of the female body?

Honestly, the presence of female figures and advertising in my work kind of happened incidentally, even though they’ve become pretty central. What I do think about more is the language I use—the medium, the irony—that part is more intentional, like “I’m going to do this.”

I often start with a recognizable object. For example, in Teddy Beer, the TV was placed on the floor, resting on two old Yellow Pages volumes. I found that choice crucial because they’re recognizable objects—shared memories.

Working with women or female characters was more intuitive. At first, I painted women just because I preferred to. Then, I realized how much was interconnected—sexualization, consumerism, and the way female bodies are trapped in these dynamics. But in my work, bodies are just that—a body, a medium through which subtle details travel, and those are what really matter. There are a lot of things I subconsciously appropriate—even things I find disturbing, like objectification. But it is what it is.

I just released a collaboration with a collective called puestoFIERA. They make artistic reproductions, and this time, we made mugs. They originally asked me to do prints, but I wasn’t really feeling it, so we landed on mugs instead. Since I’m obsessed with advertising, I wanted to make them super trashy, something super marketable. There are three designs—one with boobs, one with udders, and one with pecs. I love the idea of selling a hypersexualized object.

I’m not trying to be provocative—I’m more interested in playing with symbols. Like, I find panties funny, but I also see them as a space, a void. Sure, there’s a connection to sexualization, but I don’t overthink it too much—it just happens. (And it’s also a form of shared memory since they’re knockoff Calvin Klein.)

Do you have specific references that inspire you?

I go through phases. Right now, I don't have a clear reference. Sometimes, I get inspired by people whose work I don't even like, but for some reason, they inspire me. Among the people who truly inspire me in both aspects—work and personality—I would mention Pippa Garner. I think she’s amazing, not only her work but also as a person. She’s one of those examples where the artist and the work are inseparable.

I also get inspired by things that have nothing to do with art. For example, food inspires me a lot. I’d love to start working with food. After eating something delicious, I feel an ecstasy similar to the one you feel when you create something that satisfies you. It fascinates me because food has something very iconoclastic about it: you consume it, and it disappears. In a way, it’s like consuming an image, and that interests me. The way food consumption has evolved, just like the way we consume images, says a lot about our society.

“Little trash” inspires me a lot. For example, this disposable camera was given to me during a production. It’s a super beautiful camera, but I’m using it for a piece where I want to fill it with chewing gum, which is like a throwaway food item. I’m eating the chewing gum myself, although there’s one that my friend Álvaro put in, and I love that there’s one that’s not mine, like a special little detail.

María Arranz has also become a big reference for me recently. She’s a journalist specializing in feminism and gastronomy, and she has a newsletter that I always read. She also published a book I want to read, El delantal y la maza, and had a magazine about food and its peripheries. In the issue I was able to buy, she talks about food on the internet, and her reflections are really interesting.

Labels, posters, slogans... Is there an intention to criticize consumerism or advertising in your work?

Yes and no. It’s true that I use many images related to consumerism, but that’s not my starting point. I’m simply drawn to those labels or symbols. For example, I have a collection of candy wrappers from all over the world. Sometimes those references emerge naturally, just like I mentioned with the female figures.

I often pick them up from store windows, advertisements, or even bazaars. I like the ones with less graphic design, the more spontaneous ones. There’s something about those simple and recognizable figures that attracts me, like calendars or everyday phrases. All these pop elements are objects that catch my attention and become a mental collage that I later bring into my works.

I remember at some point I became obsessed with the idea of creating something completely unique, of racking my brain to find something only I could contribute. It’s something you grow up with as an "artist," something intrinsic to artistic education because, at some point, that was the standard. That’s why I like embracing the idea of taking things from different places—reinterpreted images, appropriation itself. It’s something that interests me a lot because, in the end, I believe that nowadays, in one way or another, almost all of us create from that place, from an enormous accumulation of references.

I think what’s more important is not falling into a constant regurgitation, into just repeating aesthetics for the sake of it. That is to say, I think the concept of an artist’s unique imprint, the "genius" figure... blah blah blah, doesn’t really exist anymore. But not trying to create something new doesn’t mean falling into empty repetition. I believe any artistic expression has to stimulate the senses, which is why I like to start from those common memories, recognizable images, and distort them in some way. That’s just my opinion—I wouldn’t want it to sound like a definitive statement. It’s kind of like when you see something you already know, but much bigger or much smaller, like in “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids·.

With the vintage references and pastel colors you use, your work conveys a certain nostalgia for childhood and adolescence. Is that intentional?

Yes, maybe. It’s really hard for me to step away from certain colors that have that teenage-girl-bedroom aesthetic, with pastel tones. I think I like the idea of innocence going hand in hand with irony, but it’s not something entirely premeditated. I think I achieve that mix by using these recognizable elements that evoke a certain nostalgia, like familiar objects or aesthetics.

I like when something can be visually sweet but, at the same time, a little unsettling, making people question it. For example, I once made ravioli in my usual color palette, posted it on my stories, and several people messaged me like, "What am I looking at?" I love that feeling of disconcerting people because it forces them to stop and think about what they’re seeing. I enjoy it because that’s the kind of experience I like the most as a viewer.

In your paintings, do you like to play with the sensation of "spying" or looking through something?

That’s interesting. It’s true that in some pieces, it feels like you’re peeking into scenes—I had never fully thought about it that way. For example, some paintings have elements that resemble little windows or holes, which add a different dimension. I’m very interested in the concept of looking in or out and how viewers interact with that idea. Maybe it’s a basic idea in sculpture, but since I’ve only just started moving away from the two-dimensional plane, this is what I’m into now.

I also like to throw people off a bit, to play with their expectations. Like I mentioned before, I love when something makes me think or forces me to stop and observe more. It’s a game between familiarity and the unknown, and I’m interested in exploring that mix in my pieces.

Installations also have a bit of a voyeuristic quality. The table setting I did with Puesto Fiera, for example, was a breakfast scene. There was a long, somewhat chaotic table—used plates, coffee cup rings, half-eaten muffins—but everything was carefully arranged. One of my best friends, who was there, told me she found it very uncomfortable, and I think it had to do with that feeling of being a bit of a spy when, in reality, it was a completely innocent and everyday scene.

Some of your early comics take place in the dream world of the characters. Are dreams something that interest you as a starting point for developing ideas?

Not anymore, although I still find this topic really interesting. I’ve kept a dream journal since 2015. In college, I was obsessed with it. I wanted to control my dreams and really enjoy those moments. I would tell myself: If I can have strong lucid dreams, I can almost live on another plane.

There was a printmaking workshop teacher who said that in her dreams, she would meet up with her boyfriend because they both had kids and couldn’t always sleep together. It’s wild, but if that’s true, why would you even want to be awake? It’s dangerous because you could end up living more happily in your dreams than in real life.

I used to work with a more magical, almost psychedelic logic, like a trip. I was really drawn to sensory alteration. There was a sci-fi book that left a big impression on me, “Barefoot in the Head” by Brian W. Aldiss. It was about a war where the biggest cities were bombed with clouds of LSD, and everyone was high. I was fascinated by the relationship between these altered states of human consciousness and how we actually use our consciousness. I was interested in the metaphorical link between these "trips" and the way we evolve. And also the limits of perception, of going beyond what we visually know.

Earlier, you mentioned your attraction to food and an IG account you created, Bocadillos Mari Tere. What interests you about this subject?

Food always catches my attention, in all its forms. But I’m especially drawn to visual formats where eating itself is the least important thing. I’m interested in how food is consumed visually, how it’s represented, and how it can be something ephemeral, something that disappears.

For example, the whole bocadillos thing started as a geeky obsession—I love sandwiches and eat them all the time. In general, as you can see, I’m very drawn to the sensory. That’s also why food interests me. But even though I like it, my artistic interest in it is more conceptual—how it’s consumed and transformed.

I recently read an essay about the transformative power of food. At the same time, I was reading “Cultura y Simulacro” by Jean Baudrillard, which talks about religion and iconoclasm—the idea that representing something kills the original because it questions its reality. That got me thinking about food as an iconoclastic element, but I still feel like I need to develop these ideas more.

Even though I love consuming food images, I feel a bit weird sharing them. If you look at my Instagram Explore page, it’s all food. But I also feel like there’s a big responsibility behind it, especially when you start thinking about where ingredients come from or the origins of recipes.

Like, you see some delicious baked ravioli on TikTok, and then you wonder: What’s the point of this? Where does it come from? I like being aware of what I do, of the ingredients, of the influences. And I also love experimenting. But at first, with the sandwiches, I got really carried away. I thought about becoming an influencer, collaborating with bars, opening a sandwich shop… the whole deal. Then I calmed down and decided to just enjoy it, do it for fun, and see where it goes.

I always think whatever obsession I have now is going to become the defining pillar of my life, so it’s pretty natural for me to get carried away. Everything leads to something. Even if I start doing something just for fun or experimentation, I eventually realize it connects to other things—whether it’s the visual aspect, the ephemeral nature of things, or even broader concepts like cultural appropriation or the consumption of images. That’s what I find interesting—letting things flow and seeing where they take me.

How does the concept of “dirtiness” relate to your work? Would you say there’s a conscious intention in your art to question or reject traditional notions of beauty?

I’ve always been interested in what’s "dirty." Before, it was more literally messing up the image, exploring the idea of ugliness, or working with concepts that oppose beauty. Now, it makes even more sense because I take things from the trash, but I think I give them something new. I remember a painting I did of a girl who looked like she had filth on her, but it was actually a glaze of dirty water. In that case, it was literal—the dirty, the opposite of pretty.

That’s a big question, honestly, because beauty is something I’m obsessed with. I think my work is a constant reflection on that. What I used to do was much prettier—if I showed you my old drawings, they’d look nothing like what I do now. My mom would always say, "Why don’t you make something beautiful?" Because she had seen me make “beautiful” things before and didn’t understand this plot twist.

What I do now still has all the aesthetic intention I can put into it—but aesthetics and beauty aren’t the same thing. It’s interesting how we relate to ugliness nowadays. That said, I wouldn’t say what I do is ugly. It’s the result of a conscious exercise in breaking away from traditional beauty. For example, the girls’ eyes in my drawings—where the whole eyeball is white—came from a mistake. But I realized they were unsettling. It’s a conventionally attractive girl, red-haired, fitting the norm, but there’s something about her that makes you uncomfortable. That contrast is intentional.

So yes, it’s a way of breaking away from beauty. Searching for something different. When my mom talks about something beautiful, she’s thinking of a hyperrealistic painting of the ocean or a perfectly realistic portrait. Something our grandmothers would consider beautiful. For me, beauty is in exploring what makes us uncomfortable, what disrupts that traditional idea of prettiness. Working with what’s dirty, what’s unsettling—but also with aesthetics in a different way. Finding a kind of beauty that doesn’t fit into what we’ve always considered “pretty.” Shaking up the senses a little bit—because honestly, we’re getting kind of dumb.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 17.03.2025