“I’m not trying to reproduce mythologies or traditional stories, but to create my own — a kind of emotional narrative that transforms into something symbolic, as if it were part of an invented folklore.” The voice of visual artist Paula Cervera is soft and pensive, as if she were carefully searching for just the right word before speaking. She smiles when she chooses that doesn’t quite fit, not wanting to seem “too confusing” as she talks about her fascination with craftsmanship, the play of light and shadow, or household objects as a point of departure for her practice.

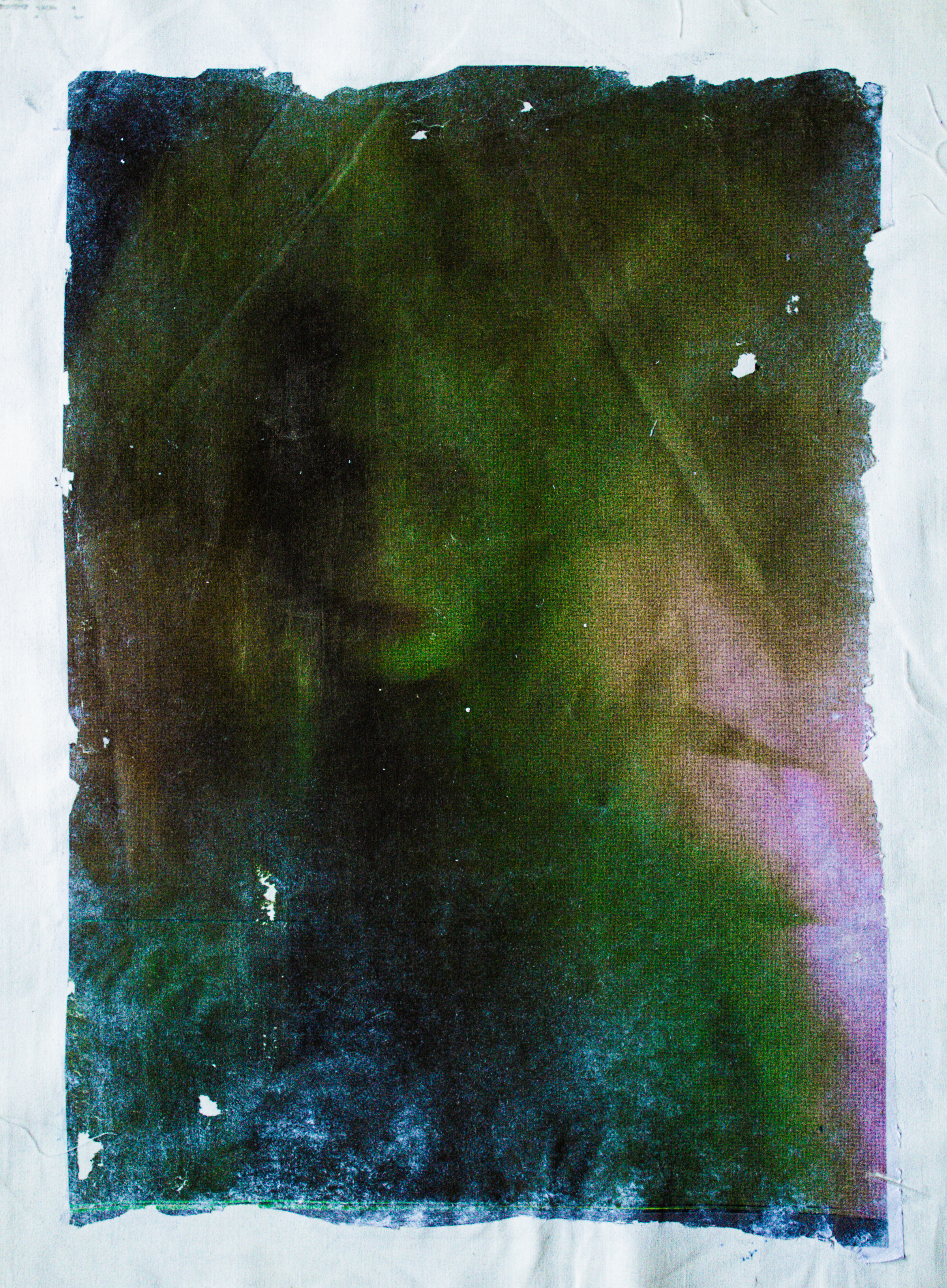

As we speak in her studio at Espacio Oculto, her sharp, penetrating gaze stands out among lace rugs, wooden triptychs, and enormous textile pieces adorned with suns, moons, and fragile presences. After studying at Escola Massana in Barcelona, Paula moved to Marseille, where she spent several years immersed in self-managed creative spaces and a great deal of artistic freedom. Now based in Madrid, she recently exhibited new works at the Aguaespejo Studio: delicate Klein blue textiles printed using cyanotype, a photographic technique she’s grown increasingly drawn to. Her pieces take on many forms, from painting to sculptural installation, always with a gothic touch and the air of an old-world antique shop. In her practice, Paula explores the visual language of the everyday in search of symbolism, recollection and emotional expression. Her work evokes a past that feels both hazy and collective, where familiar elements — bodies, faces, reflections, vases — and traditional crafts like ceramics or embroidery merge to sketch an introspective portrait of longing.

Hers is an almost theatrical sacralization of feminine desire, where intimacy, intuition, and materiality intertwine. The rest, I leave to her — she knows how to express it best.

I’m really interested in the material aspect of your work - you recur to so many different techniques! What draws you to each new one?

I think what draws me to working with different materials and techniques comes from having studied at La Massana. There, we explored many different areas, and that led me to experiment and try out various paths. I’m really interested in taking traditional techniques — which are usually intended for a specific object or function — and bringing them into a more artistic realm.

Little by little, I’ve discovered new materials and started combining them. I don’t have one favorite in particular — it really depends on the process I’m in, on what I’m drawn to at that moment, both visually and aesthetically. For example, if I want to achieve a more ethereal or “ghostly” finish, I begin by thinking about how I might get there, what material might help me express that. Or if I’m interested in a certain texture — like the one cyanotype creates — but I want to apply it to my drawings, then I research how to combine the two, how to integrate them.

It’s a process that starts with what I want to express in the work. I let myself be guided by what interests me, and that leads me to different materials. Having such a wide range of possibilities is really enriching, because it allows you to try many things and opens up lots of options. But at the same time, it can also be overwhelming — you want to do everything, but you have to choose, and sometimes you’re not sure which is best, which fits better. Still, I think the act of deciding — of choosing what to include, what to leave out, what to do now and what to save for later — is interesting. There’s something there about balancing freedom with emotionality, with how you feel in the moment. And I really like that.

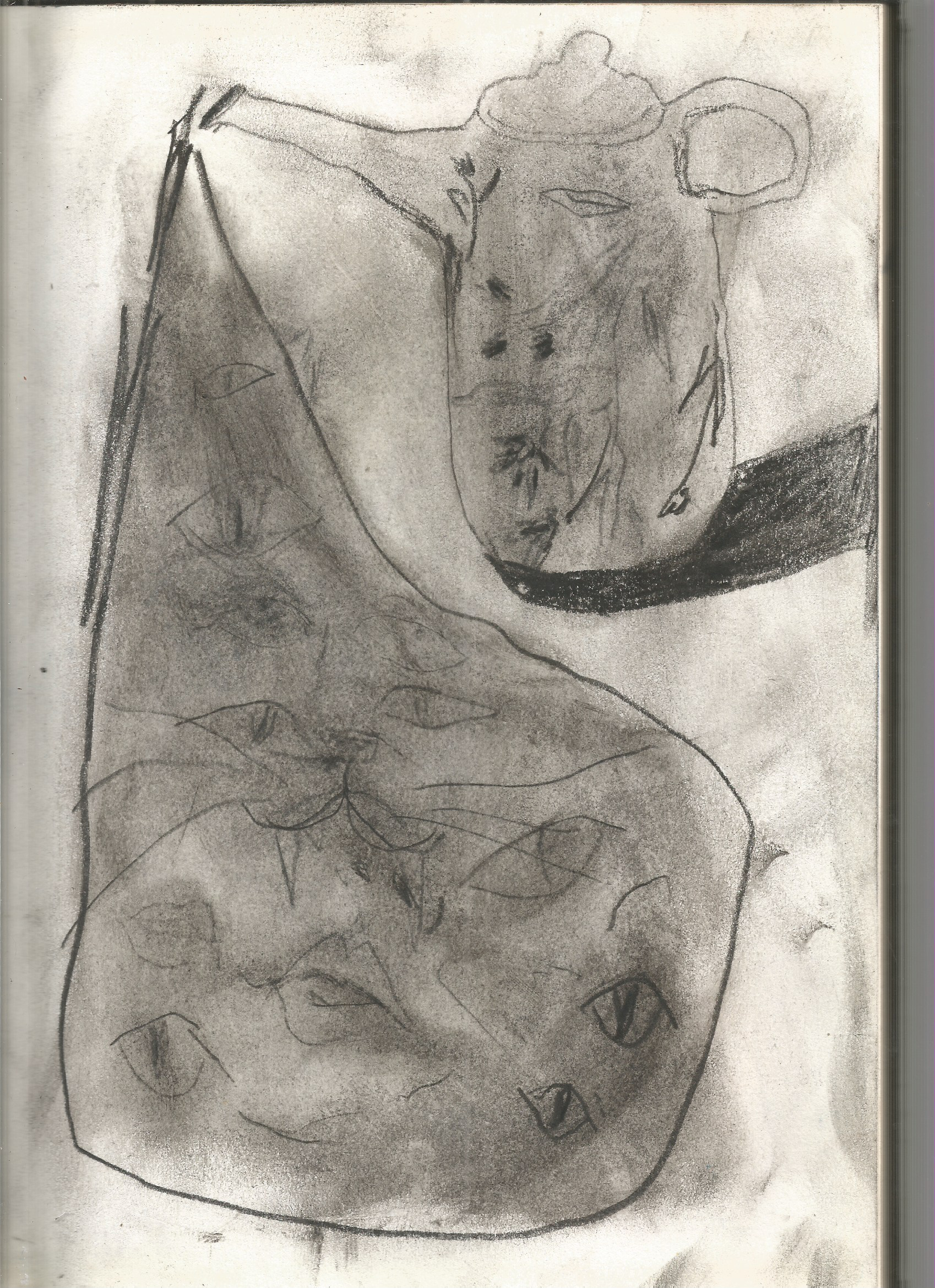

Not even from an idea, really. An idea is already something quite concrete. Although it depends. Sometimes I do have something in mind, but it’s usually more abstract or visual: a texture, a gesture, an aesthetic feeling I want to capture. So I start from that, from a visual or sensory impulse, and little by little the work begins to develop. The meaning or the concept often comes later, as if it gets built during the process.

I’ve also realized that it’s always been that way for me. Ever since I was a child, I’ve had this urge to create, to paint, to make things, without needing a clear concept or defined idea. There was never a specific intention — just the pleasure of making. And that’s something I’ve carried with me over time. The process is still very intuitive. I start by creating textures, testing out things I’m interested in, and later, over time, I see a story start to form — a meaning, a reflection. It’s like the material comes first, and then the thought follows.

Something I find really striking about your work is that all your pieces seem to come from another time, although it’s hard to say exactly when. Is that something you consciously aim for?

Yes, absolutely. There’s always a kind of nostalgia or melancholy in my work. It’s as if they’re telling something from the past, as if they’ve traveled through time. Often it feels like the pieces have already lived, that something has happened to them. And I find that really compelling.

I also tend to use symbols — icons I repeat in my drawings or paintings — that have a more traditional feel, as if they belong to another era or some ancient collective imagination. I think that comes from the visual references I’m drawn to, from that type of aesthetic. I like my work to have something of a legend, of a story told through the popular, the everyday, the traditional. That’s very connected to who I am, too, and to what surrounds me in my day-to-day life.

So yes, even unconsciously, that sense of antiquity, of being from another time, is always there. I like my pieces to evoke something that can’t be fully placed, but that suggests a story, a memory — something that’s already passed.

Have you identified what it is that you seem to be missing? Or are you interested in more of a general feeling?

It’s definitely more general. I think I link it a lot to the idea of idealization. Because in the end, we always end up transforming memories into something better than they actually were. You always long for the longing itself, you know? The past always seems better. Your mind erases the bad and keeps the beautiful, and that already turns it into something idealized.

I’m really interested in playing with that tension — with that mix: on the one hand, the memory as something beautiful and elevated, and on the other, giving it a more dramatic, ghostly twist. I like flipping it around — not leaving it as just sweet nostalgia, but turning it into something darker, even ridiculous.

Like when you remember someone you met once, never saw again, and you build up a whole movie in your head. You invent an entire story from a tiny memory, and sometimes that story is beautiful — even if it’s completely made up. I find that imaginary space fascinating: how we construct our own ideals, and how those ideals can get distorted, exaggerated… to the point of becoming almost grotesque.

That idea — that something can be so, so, so beautiful it turns into its opposite — really speaks to me. I love playing with that, with dramatizing it, ridiculing it, and turning it into a kind of ghost.

And to be more specific, what kinds of symbols attract you, or what type of legends or stories do you tend to work with?

It’s not so much about specific legends or existing stories, but more about how I build my own. I talk a lot about love stories, about nostalgia, about missing someone… all from a very emotional place. These are stories I sometimes invent, or that are born from a personal emotion I want to express. From there, I give them that legendary tone, I materialize them and express them in my own language, in my own style.

I’m not trying to reproduce traditional mythologies or stories — I’m creating my own, like a kind of emotional narrative that becomes symbolic, as if it were part of an invented folklore. They’re intimate stories, but told in a way that makes them feel old or collective — as if they’ve already been told before.

There’s a material in your work that really catches my attention, which is the mirror. It has a strong symbolic charge, doesn’t it? What does it represent for you?

Absolutely. The mirror is a material I’ve been using for a long time, ever since I studied at La Massana. It always fascinated me. In fact, my final project was a quite conceptual installation: a huge wooden structure whose interior was completely covered in fragments of mirror. The viewer would enter and see themselves reflected from different angles, in different pieces. It was something very intimate, very personal—an experience of introspection.

Since then, the mirror has kept that meaning for me: reflection, looking at oneself, the idea of self-portrait. But also the mirror as an invitation for the viewer to step into the work, to be reflected—both literally and symbolically—within it.

Besides the mirror, I’m also very drawn to other elements related to light: transparencies, reflections, shadows… There was even a time when I literally drew light, using lines. I don’t do that anymore, but I still draw a lot of shadows. This whole universe—reflections, light, shadows—leads me toward introspection, exploring the self, identity, emotion. Sometimes it’s more intuitive than rational, but it’s always there.

And aesthetically, I really like it. I feel that all these elements—the mirror, light, textures—help me build a coherent aesthetic, give a concrete image to my imagination. They help me materialize what I feel, translate it into shapes and materials. It’s a way of giving form to everything I carry inside.

In fact, something else that crossed my mind is that your pieces give the feeling of being like a diary, something very intimate. Do you agree?

Absolutely. There’s a lot of everyday life in what I do. I’m very drawn to that idea: starting from the ordinary, from the simplest or most common things, and from there elevating them into something big, something imagined, almost mythical. It’s like saying: I’m just one more person among many, but with my imagination I can transform those simple things into something beautiful, into something with symbolic weight.

That has a lot to do with popular culture too, like flamenco, for example, where pain, suffering, intense emotions that everyone can feel are expressed and transformed into something powerful, something artistic. I’m really interested in that way of elevating the everyday, making it universal. Because they’re things we all share, emotions that affect all of us.

And yes, many of my references and materials come from there: from the everyday. Reflections, shadows, mirrors, vases, flowers, a glass of wine, a picture frame… These are objects you find in any home, things you see every day, but to which you can assign a very personal meaning. I like using things that could exist in anyone’s space, but by representing them in a work, I give them a new value, an emotional weight.

I also like the idea that we all have objects full of personal history. A glass someone used on their first trip, a flower someone dried and kept, an inherited mirror… We give meaning to things, and by representing them, I’m also talking about that: the intimate significance we assign to seemingly ordinary objects. For me, it’s a way of turning the personal into legend.

Many of your pieces feature characters. I am curious to know if they’re real people, symbolic figures… Where do those figures come from?

Yes, quite a few characters appear. Generally, they’re invented figures, although sometimes they’re loosely based on people who’ve been part of my life or who are somehow present. But they’re not direct portraits—more like emotional representations, caricatures of a feeling or emotion.

When I include characters, they almost always have something of me in them. In some way, I reflect myself in them. Sometimes they even become ridiculous, exaggerating the emotions or situations they represent. It’s like taking my feelings to the extreme, to that point where the dramatic becomes almost ironic. As if they’re so intense that they ridicule themselves. I like playing with that line between sincere emotion and its exaggeration.

I think it also has to do with my personality. I’m very emotional—I like to feel things deeply, to live them intensely. And those characters are a way to personify that, to exaggerate it, to turn it into something visual, almost theatrical.

Interestingly, the characters had disappeared from my work for a while. For a time, I focused more on objects: vases, shadows, lights… Everyday elements loaded with symbolism. But recently they’ve come back, and now they’re more present than ever. I feel like, by reintroducing them, I’m giving them a leading role within the scenes, as if I’m trusting them to tell a story or embody a particular emotion.

Sometimes they represent other people, or stories I’ve heard, but there’s always a highly self-referential element. It’s almost narcissistic, honestly [laughs]. But I think it’s also a way of observing myself, of exploring myself through them.

You’ve also mentioned a fragile, almost “feminine” aspect of your practice. Does that idea resonate with you?

Very much. I think my work carries a lot of femininity, and I feel very connected to that. For me, it’s something very natural, very personal. Feeling and expressing my femininity empowers me, and I think that comes through in my work. I’m drawn to that fragility—not as weakness, but as something symbolically powerful.

For example, there are materials that remind me of dreams, of idealized things, of those constructions in your head that can break easily because they’re not real. I’m very interested in that fine line between the beautiful and the fragile, between the magical and what easily falls apart. I don’t know if it’s exactly a demystification, because I really do believe in that idealized beauty, but at the same time I’m aware that you can’t live in that state all the time. So, unintentionally, the work sometimes dismantles itself.

Another thing I thought of when I saw your pieces — especially the smaller formats — is that they felt like altars, like relics. Are you interested in that kind of aesthetic, in that relationship to the sacred?

Yes, absolutely. It’s very connected to what we were saying earlier about idealization. My imagination often moves in that elevated realm, “up there,” where things are sacred, where they’re important. I’m really interested in that altar, relic aesthetic because it connects to that space of the symbolic, of heightened emotion, almost mythic.

And in that, of course, there’s a connection to religion. Not so much from a place of faith, but from a visual perspective, from iconography. I’m interested in religion as a visual language, as a way of communicating strong ideas or emotions. I use its symbolic tools to build my own imagery, my own altars. Sometimes even with a touch of irony, reinterpreting those codes from my personal story, from my own experience.

And yes, that’s something people ask me about a lot lately. It seems like there’s something there that others pick up on, even if I’m not consciously planning it.

You have mentioned that you’re currently interested in working with installations. Do you already have something in mind or defined for the future?

Honestly, I’d love to do a ton of things all the time—I have a lot of ideas floating around. To make an installation, I first need the right space, but yes, it’s something I’m very excited about.

One of the ideas that excites me the most — even if it sounds a bit crazy or maybe impossible — is working with large ceramic pieces. At one point I started developing a project where I was exploring how I could apply cyanotype techniques to ceramics: printing drawings, collages... That kind of thing. And I’m still very interested in that—it’s something I want to keep exploring.

I imagine a space where those large ceramic pieces coexist with other materials, creating an installation rich in textures and forms. Though I’m explaining it in a very abstract way, because I’m someone who needs to start working to really visualize the piece. I can’t fully imagine it finished before diving into the process.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 26.05.2025