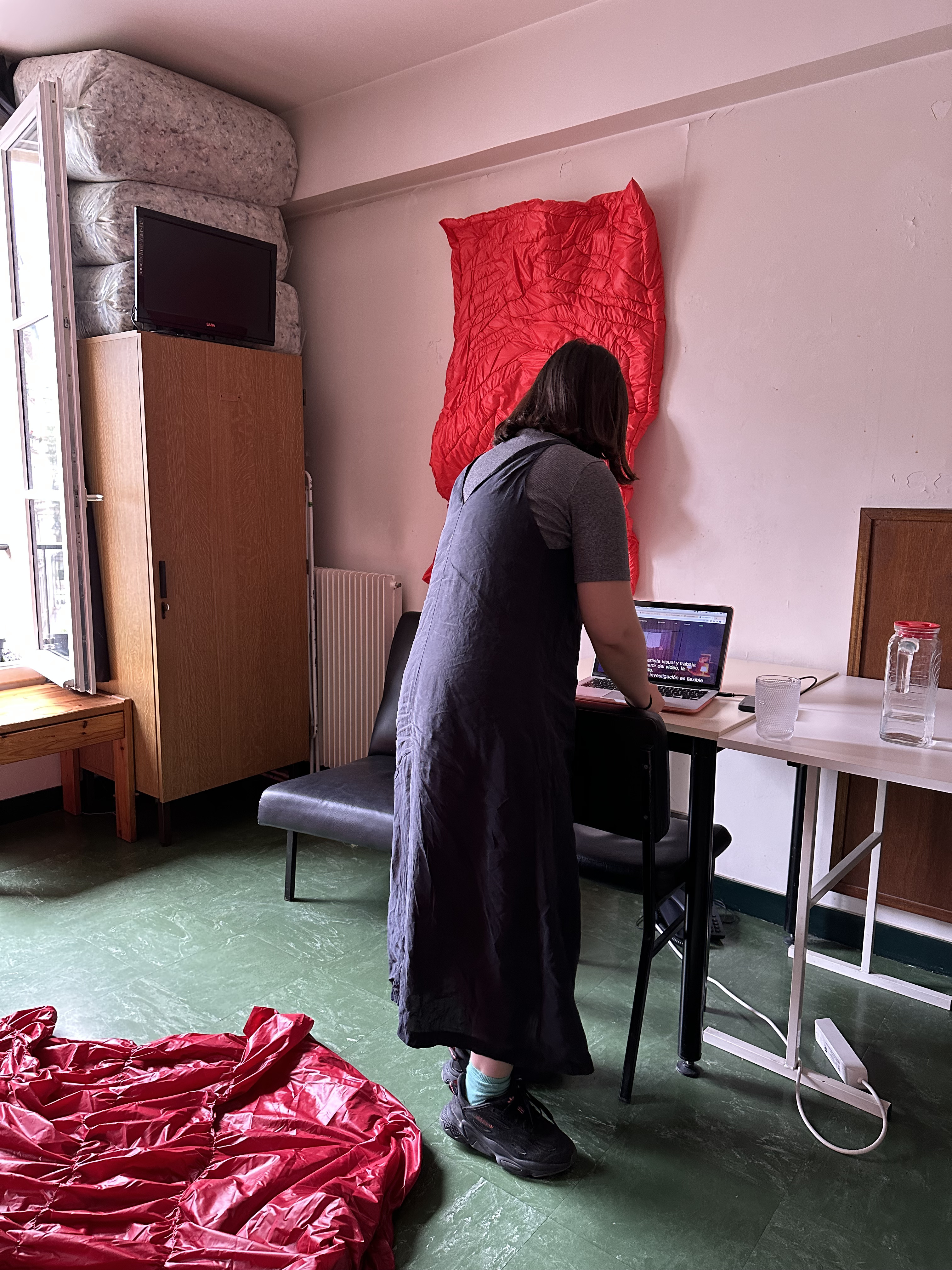

I meet María in her studio-house-room at Cité des Arts in Paris, a space so intimate that it could well be mistaken with one of her carnal installations. Inside, her personal belongings—clothes, bed, and furniture—meld with her artworks; organs, skins, and viscera drape over everything, transforming the room into something like a gigantic, inverted body.

Leaning over her visceral patchworks, María reveals details of her life. From starting her textile practice among a group of Erasmus girls to her Andalusian influences, including nods to her hometown's carnal industry and collaboration with flamenco dancers. The artist also shares her mixed emotions about her nomadic lifestyle, explored in her recent video "I have left so many times thatI don't know if I'm moving forwards or backwards...” (2023). Another one of her latest works, "Le Ventre de Paris”, (2023) hangs before us while we talk. It is a quilt of vibrant colors depicting the sinuous shapes of intestines and livers. This installation metaphorically interprets Paris' diverse neighborhoods through the digestive system, exploring the city's culinary habits and its transformation into a vast intestinal network where the metro and catacombs interweave with the international market.

The rest is best left to María's replies:

Carne de mi Carne: entraña, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist

Hello, María! You were born in Aracena, Huelva, and since then you have led a very busy life. Seville, Berlin, Barcelona… and now Paris. Can you explain your journey and what led you to move to these cities?

Since I began my studies, my life has been full of constant moves, like many of us who are dedicated to art. Each city I have lived in has affected my artistic practice, perhaps because allowing oneself to be influenced is the only way to keep creating, looking forward but also backward, trying to understand what sustains us here and now.

"I have left so many times that I don't know if I'm moving forward or backward..." (2023) is the title of the project you are developing. In addition to addressing your own nomadic circumstances, do you also intend to express a more general concern about precariousness in the art sector?

This issue runs through all my work. I grew up in a village in Andalusia where it seems like there is no access to culture, yet there are many artists, musicians, photographers... The little institutional support we receive means that all that cultural potential is lost or forgotten, and many of us end up having to leave. When we arrive in the cities, these supposed major cultural hubs, we live in sometimes undignified conditions and have to build new networks and safe spaces.

Why do you tend to digital mediums?

I usually work with digital media, although in a somewhat "pirate" manner, in the sense that I try to use these technologies to replace hegemonic images with ones that are closer to the flesh. For example, I appropriate 3D tools or pre-produced videos and, through editing and assembly, introduce them into new contexts of meaning. I always strive to carefully choose media and materials, though I am not interested in "the digital" simply because it is new, but because of the reflections it can provoke from everyday and expanded uses.

Dark Kitchen, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

In "Le ventre de Paris" (2023), the digestive system symbolizes the different neighborhoods of this city. Can you tell us about the concept of "the body" in this work?

"Le Ventre de Paris" is a video installation inspired by Zola's novel of the same name. In this work, Zola addresses social classes and the Parisian market. Les Halles, the central market, now a shopping mall, remains a place full of contrasts, where bodies from the periphery and the center of Paris converge. My project extends from the center to the periphery, exploring eating habits and the city's metamorphosis into an intestinal apparatus, where the metro and the catacombs intertwine with a new international market. Through this piece, I address this transformation, connecting Zola's novel with contemporary reality.

The first time you worked with textiles was during your Erasmus in Paris, as part of a project developed with friends. What attracted you to this medium?

A decade ago, when I arrived in Paris as a fine arts exchange student, I discovered a world of possibilities that Seville did not offer me. One of my fondest memories is a piece I created for a drawing class. With very few resources, I bought second-hand clothes, lingerie, and other garments, and with them, I constructed a projection screen. The exercise, which for me was closely related to painting, involved transforming the canvas into another space, a place where images continued to appear but also disappeared. This experience, cooked up among friends in a small room, spontaneous yet significant, profoundly marked my understanding of artistic practice.

It made me realize that I could create whatever I wanted and that each project was an opportunity to explore and learn. Since then, I have carried with me the idea that each work is different, free from commercial limitations and the need to relate to previous works. Since childhood, the textile world has always been present in my life. My grandmother was a seamstress. Although traditionally associated with the feminine, for me, textiles are much more than that; they are an affective technology that can be folded, transported, and inherited.

In many of my pieces, I use recycled and discarded materials, as in the screen "Map of Paris" (2024), whose structure was found. This approach reflects the resourcefulness so present in working-class environments, in the countryside, in villages, or neighborhoods, where everything is used, even language.

In "Cuerpo de trabajo" (2022), you investigate the famous "quejío flamenco," relating this typical flamenco lament to contemporary foods. Can you explain the treatment of this Andalusian element in your work?

In "Cuerpo de Trabajo," I explore the emancipatory possibilities of the "quejío," so distinctive of flamenco. This lament takes us on a historical journey through Andalusia, where symbols and languages have been repressed. I also reflect on our contemporary complaints, such as mental health and how we express that pain. While music plays in my studio, I sew textile pieces by machine. Depending on the flamenco style, the stitches and materials vary. They reflect different parts of the human vocal apparatus, the same parts we use to cry, scream, and express ourselves. The “Coats for Shapeless Bodies” (2022) are fluid, light pieces, made to provide warmth but take up little space.

Cuerpo de trabajo, General view, Museo de la Memoria de Andalucía, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist

Cuerpo de trabajo, General view, Museo de la Memoria de Andalucía, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist You recently designed a textile piece for a flamenco dancer. Can you describe the process of creating a piece that will also serve to express another artist's identity? What about translating dance and music into textile and visual materials?

Yes, I have been working on an inflatable "bata de cola" for a flamenco dancer. She was researching the figure of Antonia Mercé, La Argentina, and I was working on "La romería de los cornudos," a ballet by Federico García Lorca where this artist was supposed to appear, although "La Argentinita" eventually did. This confusion brought our processes closer and made me think of Bacarisas' costume designs for that same piece, very airy and voluminous. From there, I translated the forms I was manipulating at that moment with the "Cuerpo de trabajo" project and those “Coats for Shapeless Bodies” into a piece that can actually be worn. This contemporary version of the "bata de cola" was born from there. It could well be a project by architect Prada da Poole.

Which part of you inspired the project "Carne de mi carne" (2023)?

"Carne de mi carne" is a very important work for me. It consists of two parts so far, with a third to be added soon. This project is organic in nature; it began with available resources and has developed in the best way possible. Winning the Generaciones 2020 award was crucial, giving me the time and space to write, reflect, and pause. Through this work, I constructed a sort of fictional documentary about my own family, originally from Aracena, a region with a significant meat industry both socially and economically. Inspired by the reflections of a French anthropologist, I explored the possible implications of patriarchy in the relationship with meat, from the division of labor to stereotypes about rural life and gender roles in those contexts. Through family experiences, this project unravels the complex economic and social dynamics rooted in the meat industry in rural areas.

Carne de mi Carne: entraña, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist

In 2022, you co-founded Grotta, an artist residency in the Sierra de Aracena. How did this project come about?

Grotta is a project born out of my passion for artistic collaboration and collective creation. During the residencies in the Sierra de Aracena, we aim to foster creative exchange and artistic exploration in a natural environment. For me, artistic collaboration is a way to enrich my own practice and learn from other artists.

You are currently working with a research grant at the Pompidou Center in Paris. Looking to the future… Would you like to continue combining your artistic practice with research or curating?

Research is an integral part of my work, either as a way to approach artistic practice or to produce knowledge. I can't say clearly what my future plans are, perhaps because our existence as cognitive workers forces us to remain in this endless chain of projects. However, what really attracts me to this way of life and work is the ability to constantly explore new ideas. I dive into archives, connect with new people, and am always on the move. Although I don't know exactly where I'm heading, I know I'm on my way. My experience in museums, both in terms of research and curating, has opened my eyes to a world that increasingly fascinates me. I'm not sure if I will ever fully dedicate myself to it, but I've learned a lot about institutional dynamics from the inside. It's a complicated but fascinating world, where institutions not only reflect what is done outside but also influence it. In the next 10 years, I would love to continue exploring and discovering new horizons in my artistic practice and in the institutional field.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 19.06.2024

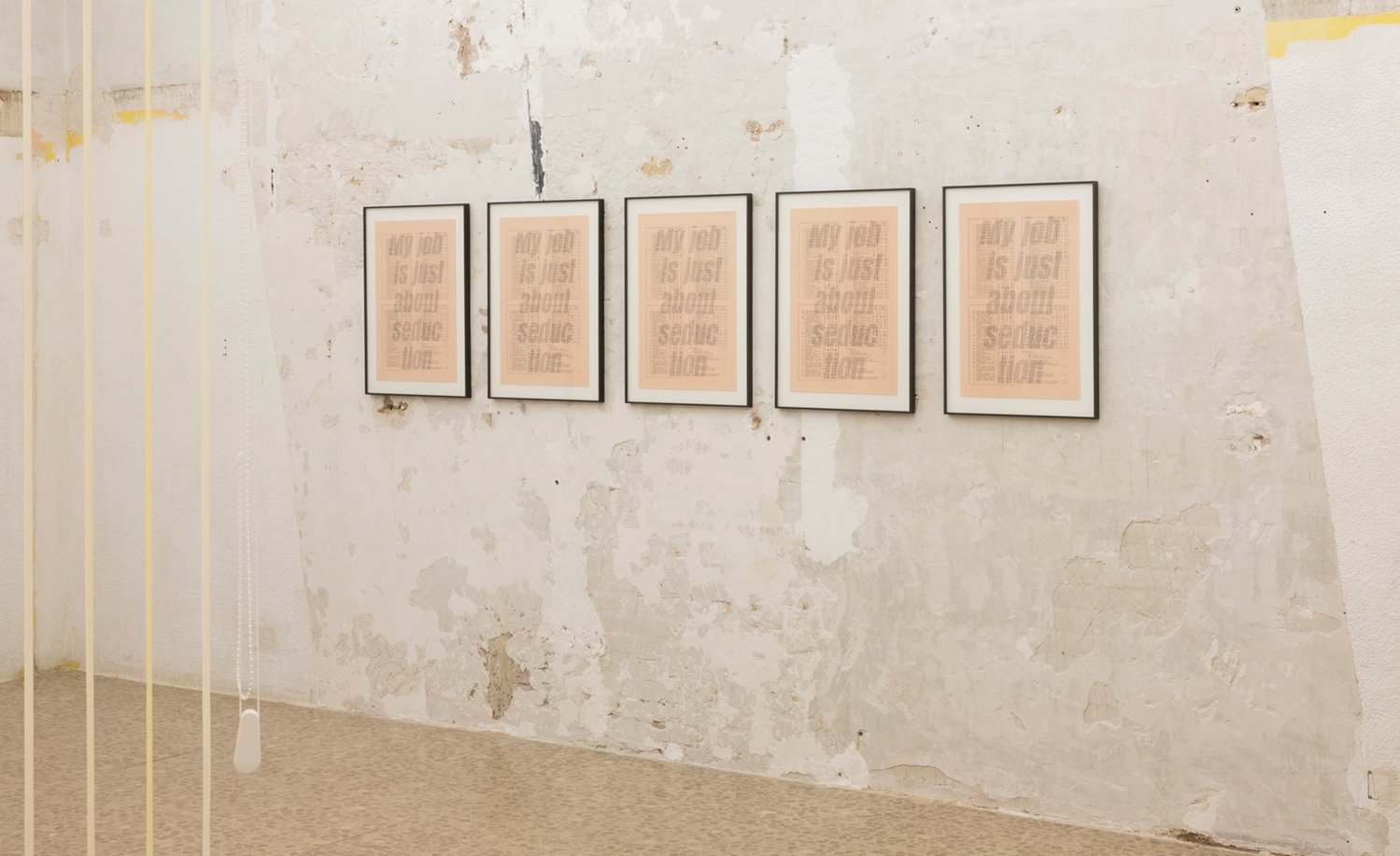

My job is just about seduction: Alicia, Flippo, Paula, Luis, Constanze, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist

Carne de mi Carne: entraña, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist