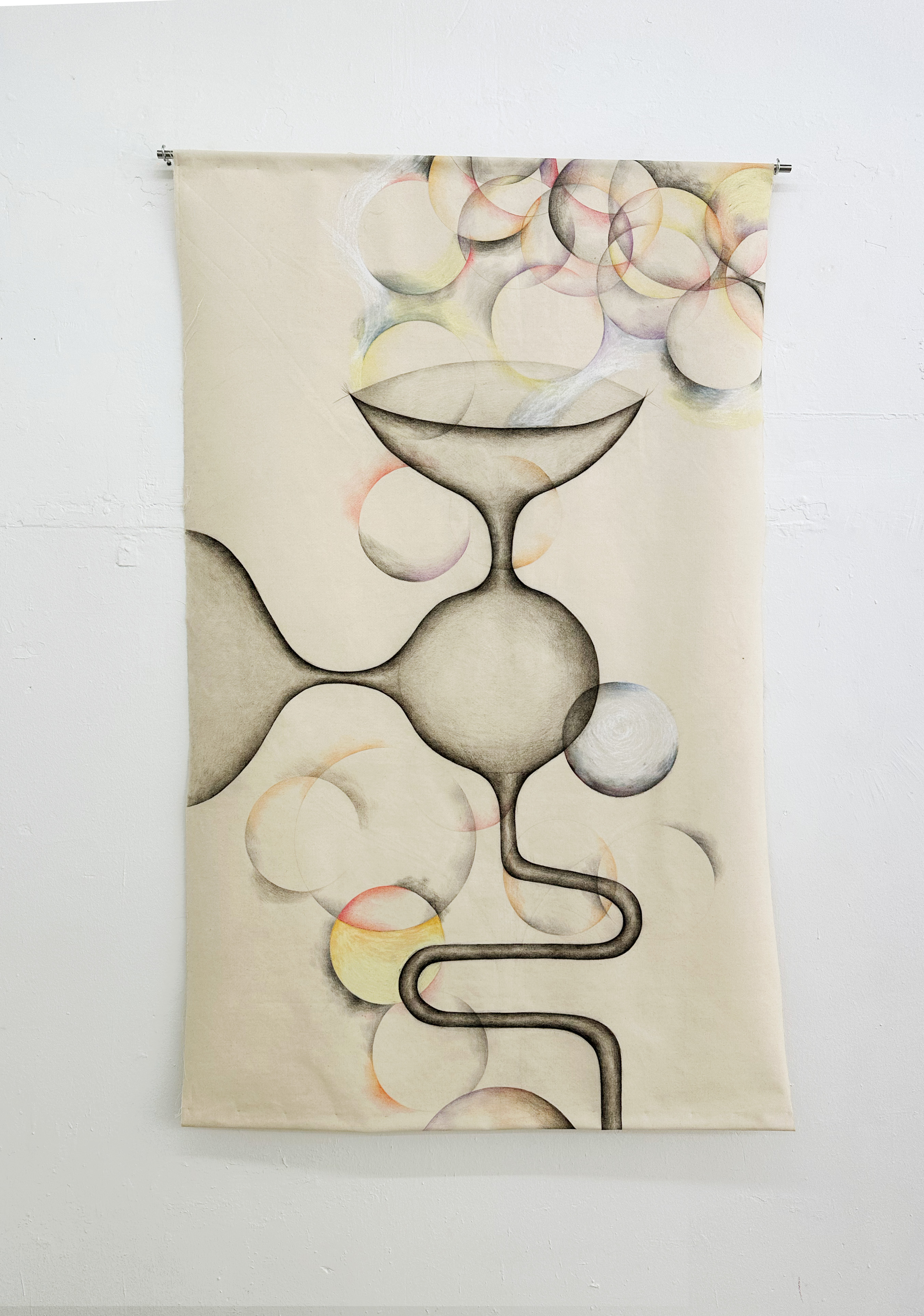

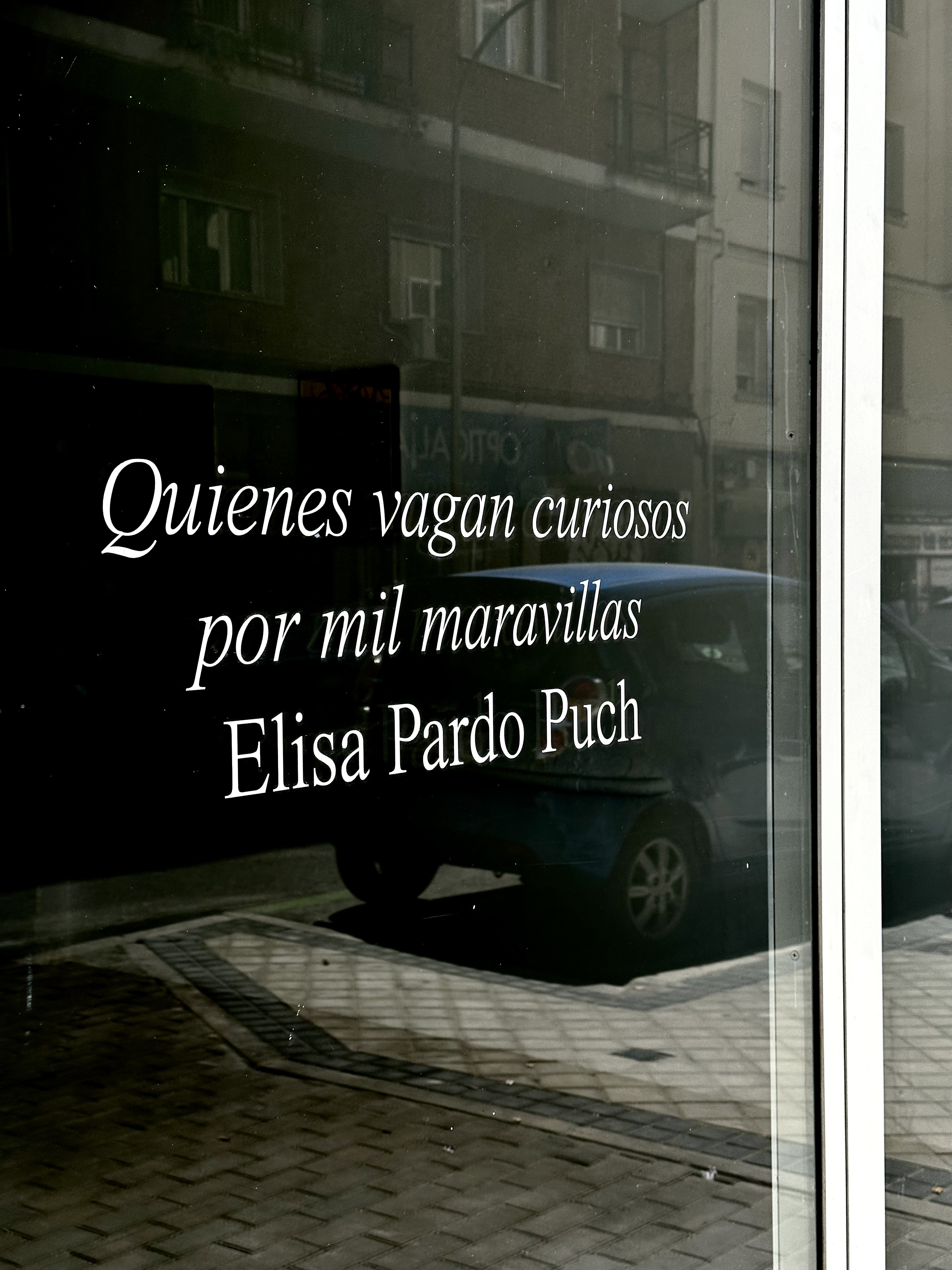

I follow Elisa through Pradiauto gallery, transformed by the artist into a fantastic room full of repetitions, as if it were a hall of mirrors. Her solo exhibition “Quienes vagan curiosos por mil maravillas” puts forth an intruiguing universe where she pours feverish dreams, perceptions and a longing for something she seeks through paper and pencil but cannot quite define.

There, where cabaret dreams intertwine with Berlin's nocturnal lights, music, artists from other eras, and a sweet, comic sordidness. Her pieces breathe with their own stories and those of others, interweaving a multitude of contrasts—the repugnant, the light, the tactile, the disposable—speaking of private and shared memories. A space where narration becomes a loop and constant repetition, a spiral, a tongue that traverses a room like a macabre invitation to partake in a strange game of spoken and unspoken realities. A search that is matter itself, or matter as search, or the scribble on paper as redemption, location, and encounter. Textiles as a historical space where the voices of many find an echo through Elisa's hand.

And through her own words:

Image by Pradiauto gallery.

Hi, Elisa! Repetition of patterns is key in your work. Why are you so interested in mechanical repetition? Is there something meditative in your way of working?

In many of my projects, repeating a certain pattern forms the basis upon which to start generating variations. It’s as if it were my way of approaching the projection of an idea, of entering the drawing to then try to escape from the grid I’ve created.

The small variations I generate are what interest me the most, the little changes. It also has to do with the movements I make while working. My way of drawing and sewing involves repeating the same movement over and over again. It might be something meditative, something that allows me to enter a state of concentration.

You have worked with the symbolism and history of textiles, for example, in "Manteles" (2021). What attracts you to these materials? Do you think there is a feminist intention in using a material traditionally associated with women's crafts?

Textiles attract me as a material, as an object that unfolds and occupies space, adapts to other surfaces, can be folded and stored. It’s a less imposing way of existing. They also contain a different temporality, allowing one to imagine the people working on the pieces, the time it might have taken to create them. They appeal to the body, to touch. And they are also more perishable materials, they can tear, deform.

Yes, there is a feminist intention in using textiles. For me, it’s a material that feels very familiar when working with it and is historically linked to women's work. It’s a contradictory space because women were relegated to it, but at the same time, it was taken up by many as a field of production, transmission, and preservation of knowledge and experimentation. Additionally, sewing created safe moments and spaces for encounters among women. I use textiles because, by doing so, I inevitably talk about the silenced history of women's work.

In the piece "Manteles," I reference an unverified story about the checkered race flag, which is thought to have originated in the 19th century in the United States at horse races where men competed, and women prepared the food in the field. To stop the race and start the meal, women would wave tablecloths.

I have worked for many years as an assistant for other artists, painting their watercolors, and this patchwork is made with a cotton fabric that I used as a cloth to clean the brushes while I worked for them. As if it were a trace of my work, a calendar of time dedicated to the enrichment of others. That piece talks about the hidden stories of those who really keep things running.

In the description of your work "A Strange Fairytale," you mention "The Thousand and One Nights" and the myth of Ariadne's thread, where narrative structure is a fundamental element in each story. Why are you interested in these references? Can you talk to us about the “narrative” component in your work?

In some of my works, I appeal to concrete events in my life, but also to external ones. This is the more narrative part of my work, where connecting experiences is the starting point to generate a piece, and that fact is included in the explanation of the work.

Regarding "The Thousand and One Nights" and the myth of Ariadne's thread, these stories interest me because their narrative structures are part of the story itself. They make the construction of the work explicit, a game between fiction and reality. I’m interested in works that move from one place to another.

Image by Pradiauto gallery.

When we met, we talked about a lot of movies, songs, and artists that inspire you. Can you mention some of your main references?

When I work, many things inspire me. In this latest project, the starting point was the movie “Lola” by Rainer Werner Fassbinder; the lighting in some of the scenes and the squalor in the films of that director; the complex, dark, and simultaneously luminous characters...

From the movie, I became interested in the phenomenon of cabaret in Berlin, especially during the Weimar Republic, the artists who developed it, and the social and economic characteristics that fostered this scene. It was a moment of great cultural freedom and great poverty.

The title of the exhibition “Quienes vagan curiosos por mil maravillas” is a phrase translated from the song "Das lila Lied," a German song from 1921 that is a hymn to sexual freedom.

Although in each project I may have different references, one that has remained is the work of artists like Gunta Stölzl or Anni Albers, and in general, the work done by the Bauhaus, a movement that almost aimed to encompass every aspect of life. I’m very interested in that utopian idea that art and shared knowledge can improve life.

Image by Pradiauto Gallery.

You told me that in 2023 you made a series of drawings while you were sick and had a high fever—how did this experience differ from your usual way of working? In general, how much intuition, planning, or spontaneity is there in your processes?

This series of drawings happened when I returned from spending three months at an artist residency in Munich. I spent a week in bed with a fever and during that time, I started drawing. My body hurt, and I tried to think of something pleasant, to induce well-being through thoughts: I imagined currents of pleasure running through my body, relieving the discomfort. Those forms that entered and dispersed within me were the forms I drew, like someone taking a picture of a lightning bolt. They were forms obtained by imagining those discharges frozen in time. This was the first time I used an altered state of consciousness to create a series of drawings, something I don’t usually work with.

In my process, there is a lot of planning in the textile pieces, and the process is longer. I design the piece, design the patchwork pattern, cut each part, and then sew them together again. Once the first layer is finished, I quilt the entire piece and sew it again to highlight the geometric drawings.

The drawings are more spontaneous, and the process is more instinctive, modifying the image as I go. However, I try to maintain coherence among the drawings that are part of a series.

In your latest solo exhibition at the Pradiauto gallery, “Quienes vagan curiosos por mil maravillas,” you mixed your two main techniques, drawing and textiles, for the first time. Why did you make this decision? How did you find the process and the results?

My language branches into drawing and textiles, with a continuous tension between the two-dimensional and the three-dimensional. Many of the drawings are projections of spaces, and the sculptural pieces are made up of seams that are also drawings. In “Quienes vagan curiosos por mil maravillas,” I wanted to create a piece that united these two worlds, a hybrid body, a kind of machine that unfolds and contains all my language.

The central sculptural piece is made under this idea, an artificial body that unfolds in space, softly invades it, and contains everything I’m interested in working on now. From the drawing, a black plastic tongue emerges, falls to the floor, and reaches the gallery door, which can also be interpreted as a path to enter the drawing.

Instead of sewing the different parts together, I joined them with metal springs, contrasting with the softness and suppleness of the other materials (cotton fabric, plastic bags, and batting), taking the piece to a more playful side, as if it were a giant toy. It also references mattress springs, which combined with the textile pieces, lead me to see that strange object as something intimate.

Across the exhibition room, there’s a giant plastic tongue that also represents a quilt. I’m interested in the contrasts of this piece, which simultaneously generates repulsion and attraction. Why are you interested in opposing these sensations?

What interests me is the feeling of strangeness that can be generated by seeing an object you think you recognize as familiar, but something strange has happened to it. The feeling of not fully understanding something is what interests me when conceiving a project, and also when I try to put myself in the shoes of another person visiting the exhibition. Not fully understanding things is what keeps me curious and eager to do and experience more things.

The premise of the exhibition is to create machinery that is about to explode, releasing a strange substance. Is this also linked to an inner or emotional exploration?

The premise of the exhibition is to create machinery that is about to explode, releasing a strange substance. Is this also linked to an inner or emotional exploration?My approach to drawing is very intuitive. I draw without creating preliminary sketches. I suppose by confronting the process this way, I allow what my hand translates into a drawing to be very connected to my emotions. While drawing, I kept in mind the idea of a channel containing something hidden in motion and the sensation that can be generated when the hidden is finally released.

Both Sofía, curator of Pradiauto, and you mentioned that you feel the exhibited works are increasingly "refined" and straight to the point. Where do you think this process of, let’s say, “maturation” will continue?

I think this has been due to a more focused work process. I produced the entire exhibition in Berlin, at the GlogauAIR residency. From the moment I arrived, I worked a lot, experimenting with mixing drawing and textiles, drawing on different fabrics, making pieces that could be used by a body, mixing drawing, text, and painting. After all that production, and thanks to Pilar Soler, I began to make decisions and let go of some things I had started so that the pieces in this exhibition would be more focused on the same language and concept.

You are currently a resident at GlogauAIR in Berlin, where you have been developing your work for a few months. How do you find the art scene in Berlin compared to Madrid and Spain in general?

In Berlin, you can still feel that there are quite a few resources to sustain the artistic fabric. There are public grants, many institutions, and projects with programs to turn to. I feel there are different scenes, not just one, and for an outsider who doesn’t speak German, it seems difficult to enter.

Although there are still many artists living here, from what people who lived here ten or fifteen years ago have told me, things have changed. The city is very expensive, and the opportunities are fewer.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 06.06.2024

Image by Pradiauto gallery.

Image by Pradiauto gallery.