I hop down the stairs that lead to Granada-based artist Carlos Cañada’s studio, a graffiti paradise illuminated by an intense white light. Carlos sits in front of me like a monk, legs crossed on top of his small chair, hands on his knees, ready to talk to me about his latest series of paintings, "The Searchers" and "Dalton Variations."

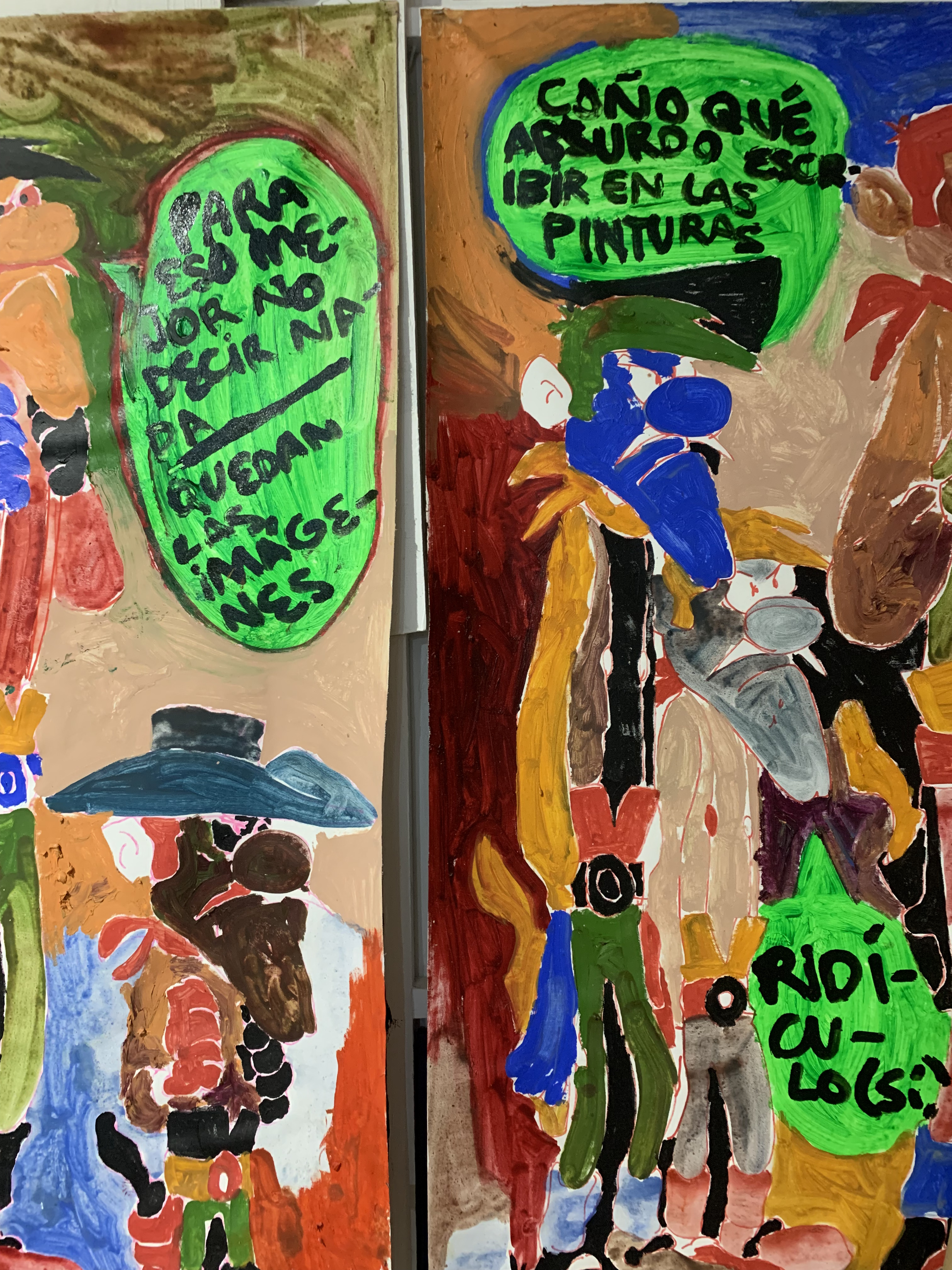

Painting is like an object, he tells me. Scattered on the floor are his latest works, canvases almost two meters long. On one side, “The Searchers”, a series of paintings whose protagonists are cowboys outlined in stylized black strokes, like a comic book. Next to them are the twenty works that make up “Dalton Variations”, an explosion of colors pierced by painted messages: Fuck, so absurd to write on paintings…! Carlos tells me that since 2021 he has been looking for a more intuitive way of creating, without restrictions or previous planning, an escape route through which to express without barriers, while he prepares his doctorate on negative theology at Faculty of Fine Arts in Granada. In “The Searchers”, the cowboys are in the midst of a pseudo-mystical crisis, but, as Carlos tells me, "as a joke - I wanted to work on it in a relaxed way, to go back to the basics of life". The Daltons, for their part, give voice to rabid meta-artistic reflections on creating and being an artist, wrapped up in frustrating situations. According to Carlos, because they think too much.

The artist talks to me about quietism, Aragonese clerics and religious anarchism, intermingling this chit-chat with reflections on failure, excess of reason and the search for the infra-ordinary in art. After some hesitation, he says he remembers a phrase by Andy Warhol that might clarify it all, something like "As an artist, I am a garbage man. The richest person in the world is the one who has an empty room." The rest of the explanations are best left to him and his own answers:

In your latest series, “Los Buscadores” and “Variaciones Dalton” you have returned to painting, a technique that you had dropped in recent years to focus on others, such as video art. Why have you decided to take up the brushes again? Would you like to continue down this path, or explore new mediums?

When I did the project using video and photography, "Loco que decías/ nunca más/ rápido/ repítelo", I didn't feel like painting made any sense. So I focused on proposals where the medium had to be necessarily different, hence the recordings. Using that language has to do with contemplation, even with fatigue, with zoning out, and also with everyday life. We record and photograph daily, it's something that transcends art. But painting at that time was too gratuitous for me.

Later, when I had somehow settled the matter of the recordings, I was able to return to the pictorial language. Understanding that painting effectively seems to have no sense, the lack of a "why," is also the most important thing for me. It's playful, you have to let go a little too. In addition, in the previous project, the record was very different, the position from which I spoke was different. I mean on a vital level, and therefore also in the artistic aspect that had to be reflected. About the future, I wouldn't know what to say really.

These works feature characters inspired by cowboys and highwaymen, such as Lucky Luke and the Dalton brothers. What attracts you about bandits and outlaws? Are they included in a symbolic way in your work?

I'm not sure if they are a symbol, I couldn't say what they symbolize, rather they are something like a mood. I think I started to relate, more or less by intuition, the artist with the bandit. Analyzing it afterwards, I think it has to do with how the artist can, through their practice, escape rational thought patterns, but I don't think that was the origin of these paintings. It had more to do with a certain guilt, as in the series "The Patient," which is about a serial killer who wants to stop being one and kidnaps his psychologist for help.

In "The Searchers," I wanted to speak from a place of failure, and I started creating these outlaws in search of redemption. To do this, they follow pseudo-mystical processes. They want to find enlightenment, but they can't. The Dalton Brothers are still bandits, but it's something else. These paintings generate a different poetics, because of the style and the use of text within the image, although the idea of the bad guy as the central theme of the painting remains, in addition to the attention to perversity as the basis, I think that is present in both projects.

In addition, the gunmen, as an archetype, seemed interesting to me in the sense that the Wild West, as an ideal, is a simulacrum, a fiction. Our context, the spaghetti-western, is even more fiction, and at the same time completely real and close. I liked the idea of pointing out in an obvious way the simulacral nature of art, as I understand it. I was interested in starting from an obviously fictitious plane, which is why I turned to cowboys.

As part of your doctoral research, you are studying Christian mysticism and the idea of negative theology, which involves reaching spiritual revelation through non-rational techniques such as contemplation. Are you looking to explore something similar in your latest works? In what way are both paths (the academic and the artistic) related in these paintings?

I feel that there must be a very primary relationship between the experience of spirituality that mystics have and what I/we do, but I have never wanted to present painting or art as a type of mysticism, nor am I trying to explore the negative path through painting. It is more the opposite. I started thinking about it when I tried to rationalize the artistic experience. Non-doing can be interpreted in several ways, such as non-creative writing, by Kenneth Goldsmith, which I find very stimulating. But what I am trying to focus on in my research is rather the lack of intention. I mean, what I am investigating is the idea that art - the one that interests me at the moment - is not controlled, it is channeled.

In this sense, I believe that the non-action of mysticism has something to say in artistic practice. It is not a matter of transmitting a message, which therefore has a prior discursive elaboration, but rather something like speaking with existence through practice, questioning what is intuitively forming before you. And if necessary, rationalize it later.

Trying to consciously apply this to my paintings is in itself a betrayal of what I just said, in this sense, I am seeing how to maintain balance without over-analyzing things, so as not to be like the Daltons that I have painted. On the other hand, speaking of the relationship between artistic practice and academia, I do not see friction between art and research, but rather between art and institution. I try not to think academically when I paint, but my production is the germ of what I investigate.

In order to produce these works, you have used old bed sheets as canvases, randomly choosing colors, and, whenever you made a mistake you corrected it manually so that it would be noticed, in what you described as “leaving the trail of shit”. Why have you settled for such a non-perfectionist way of painting?

I think that more important than "knowing how to paint" - whatever that may mean - is knowing when to stop. The perfectionism you mention fossilizes the image, in my opinion. Furthermore, in my case, too much optimization in the process prevents us from expressing ourselves, both the image and myself. I began to realize that when I covered or corrected the stroke, and so the process became a constitutive part of the image.

I worked with used sheets, and I invented a primer that would suit the technical needs that these fabrics created, and this gave rise to a very particular quality of the surface: very porous, easily cracked, very rigid, and of a yellowish white. When covering mistakes with white acrylic, they became evident, with different shades of white. How the surface is worked upon, how the drawing process is… All of that is as important, or even more important, than the final image.

In Dalton Variations, I did use primed cotton. In this case, the dynamics were different. I wanted to generate the greatest number of images in the shortest possible time, without prior reflection, thinking in the moment, creating the same image twenty times. I think that without restrictions, there is no creative freedom. By creating such a defined framework of action, one can focus on something else. If you already know what image is going to come out, what is left for you as a painter then? That's where the game starts. In the Daltons, it's not that I'm covering up mistakes, it's that each image comes out as it comes out.

The protagonists of "Dalton Variations" are portrayed reflecting on different aspects of art, like absurdity and language, showing anger and disappointment. Are these expressions meant to ironize artistic processes? Do they express your own thoughts on this?

I don't necessarily support everything that the Dalton brothers say. In fact, since I created them so quickly, I'm not sure what most of them say; I only remember a few phrases. Many of the phrases are mine, others are thoughts that move me in one way or another. In reality, they don't say much, often there is not a differentiated thought, but rather an impulse or drive. The Daltons here are like a collective consciousness; through their multiplicity, they express a common but indeterminate thought that takes shape as the texts relate to each other. They show anger because they are the bad guys in the movie and things aren't going well for them. There's a lot of reactivity there. But I didn't intend to be ironic; it's just the default way it came out. I didn't have much of an intention, just to make paintings.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 26.06.1997