METALS, METEORITES AND MAGIC

A historian, anthropologist, philosopher and scientist. Salomé Lopes is all of this and yet none of this. A shy quiet artist on the outside, who internally is nothing less than a genius alchemist plotting plans in a Mediaeval tower.

Coming from a background in Fine Arts, Salomé’s work is centered on scenographic installations that revisit established structural narratives, from prehistoric times until now. In her latest work “Sideros” (2022-23), Salomé has constructed a space of suspension that spurs the viewer into a state of doubt, blending metal in a mixed-bag reinterpretation of symbols from different ages. I first saw the early stages of this piece before I had even met the artist in person. I was immediately struck by its mysterious structure, and thought that it could well be a meteoric remnant or an alien spacecraft, covered in all types of objects... Ursula K le Guin could have described them best: “A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container. A holder. A recipient.” Metal trinkets, shining cups, succulent berries and delicate lilacs, all ringing with a feminine vibrancy, like a portal to a parallel reality. I was drawn to its alluring presence, and was even more moved by what I found out later on. Eclectic research on alchemy, ancient Greek texts on love and longing, meteoric discoveries and even a course in astrology that Salomé undertook to find out more about human belief systems.

I now see “Sideros” as an extension of the artist’s unique mind: a scenario of scattered connections that somehow make sense, mixing atemporal symbols, ancient myths and unique materials into a tapestry of glinting possibilities. You’re probably quite intrigued, so please read her replies:

Hey Salomé, between solo and group exhibitions, the last months have been a blast! Going back to the start of “Sideros”, can you explain why you first became interested in metals? How has your view of this material evolved since the project began?

Hey Salomé, between solo and group exhibitions, the last months have been a blast! Going back to the start of “Sideros”, can you explain why you first became interested in metals? How has your view of this material evolved since the project began?Hey! I think the core of this project emerged way earlier than the work itself. My interest in metals started in 2020, in a class about megalithic monuments, and it took shape when I read some texts related to this topic, such as “Blacksmiths and Alchemists”, by Mircea Eliade. That was when I discovered a relationship between celestial cults, meteorites and metal. I was interested in the way that this original encounter between metal and the sky is present in stories and myths, and has been passed down through generations, becoming an inherent part of its meaning.

In the book, Eliade says that prehistorical tools made of meteoric iron have been found in several parts of the world, prior to the Iron Age. He suggests that, since the material came from the sky, it was likely believed to be a gift from the heavens. So, this «celestial» origin became part of metal’s symbology, and it was probably the start of its numerous magical, religious and spiritual connotations throughout history. He also explains how this manifests through language.

He mentions, among others, the greek word for iron, “Sideros”, which gives the name to this work. It’s believed to derive from the root Sidus, Sideris «star», and from it come present-day words like sidereal (sidereal space - outer space), and siderurgy (metal work). I was fascinated by this correlation, not only because it is beautiful, but also because it’s an example of how deeply our origin stories can linger without us even noticing.

After discovering all of this, I wanted to work with metal — to actually work with it with my hands, using basic tools. I remembered the few experiences I had had working with metal through etching, and I always found the process to be almost alchemical, as if I was working together with the metal to create something: an image. So, when I started this project I decided to sculpt the metal vessels using the metal drawing technique, which means you shape a metal plate using a hammer.

It was truly a process of working together with the metal. It brought me many troubles, and it felt to a certain extent like the metal had free will to decide where to take me. Any force I applied to it only worked if it wanted to. Thus, many of my attempts were failures, and some accidents gave body to the pieces. This slow, physical and arduous process was something that drew me closer to the work. I felt a connection to the history of the material and its connotations, and also the meditative hardship of working with it.

“Sideros” interprets different religious and historicist items, such as altars, banners and chains. Is there a link between this mix of atemporal symbols? What do you mean to put forth by combining them all?

I really don’t know why I chose those elements, or why I decided to combine them. I think all of that is the result of an intuitive process that I can’t break down into words. Maybe it’s explained by my desire to work with anachronism, creating situations that feel familiarly distant, although they cannot be located in a specific time.

The idea of the altar has been with me from the beginning, and I think it is the most important one. I was thinking of the altars (“alminhas” in Portuguese) that a traveller can find along their journey, scattered in rural roads all throughout Portugal.

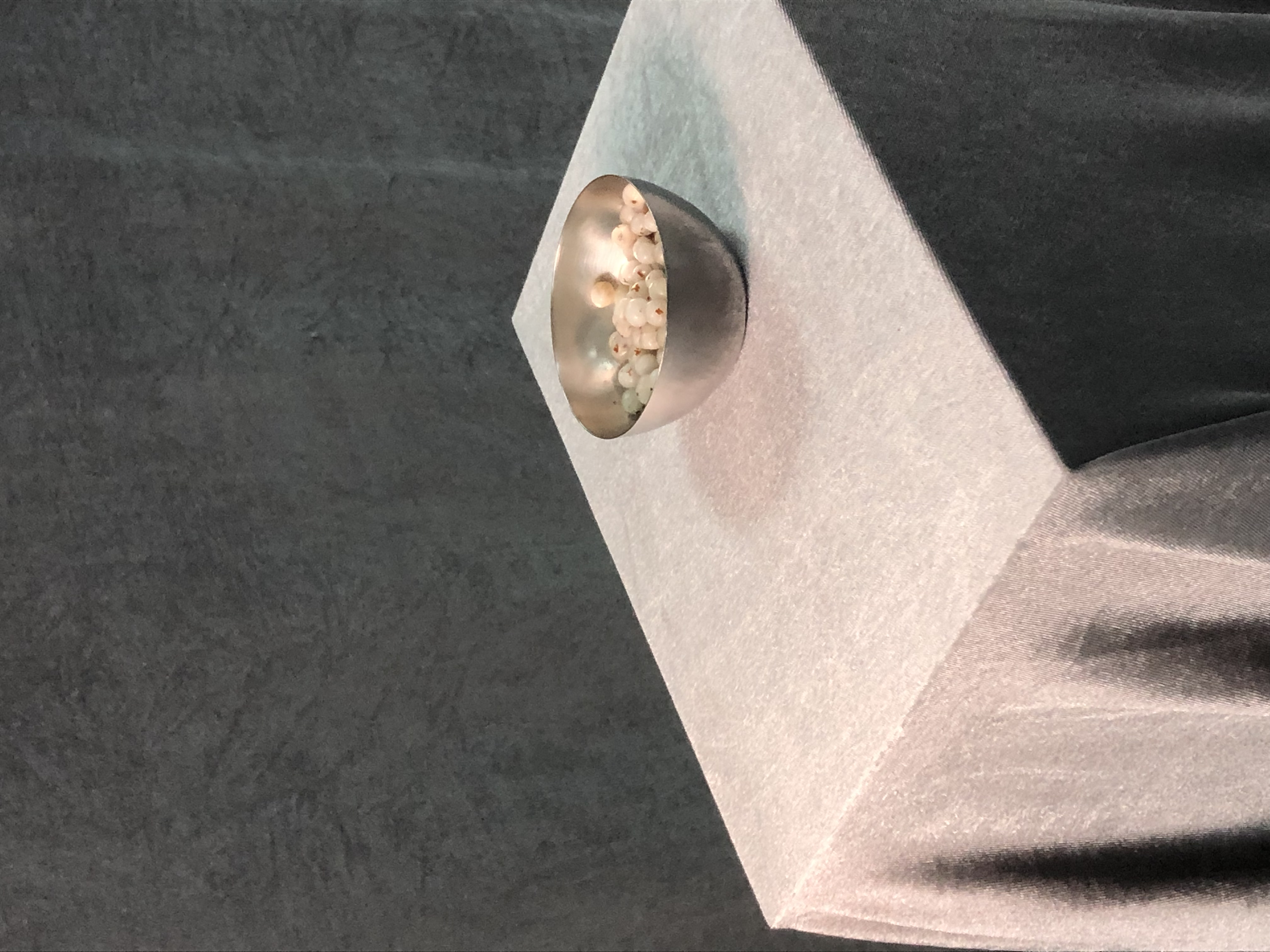

They are small, domed structures, containing a saint or a virgin inside — all vertical structures, just as the traveller. I was perhaps interested in the idea of stopping along the journey to pay worship or to receive a blessing, just as I was interested in the inaccessibility of the berries, only found on the sea slopes in the summertime. There is something about the traveller, its dynamic nature, the seasonality, the forest, the cliffs, that interested me. Plus, the altar, from a more general point of view, is the surface to sustain, the place where something must be performed — a prop for an action, which interests me greatly.

I’ve been interested in vertical shapes for a long time now, maybe due to my fascination with cathedrals. Perhaps the fabric and shelf hanging from chains were an attempt to create a window, a portal, as a way to explore that same height, weightlessness and verticality.

On the other hand, the banners for me were the best format to present the embroideries as a way of storytelling. I like the seriousness of the still image embroidered on fabric, almost as a coat of arms, conflicted with the creation of a sequence, a narrative.

Why do you choose to actively involve audiences in this piece? Can you further express the idea of “ritual” you mentioned during our talk?

I have always been interested in involving the viewers, and that’s why I work with installation. I think of the work as something that is created in the space between objects, that only exists when it is experienced. Moreover, I’ve become progressively interested in the dissolution of the work of art as an object, aiming for it to become more of an experience.

In this particular work, as a reaction to previous ones, I was trying to create an inviting and pleasant experience. I had this image in my head of people telling stories around the fire. For me, this is the primary act of reunion, of sharing, of telling stories, of passing down information from generation to generation — In short, the beginning of civilisation.

That was the origin of the idea of ritual. I wanted to reenact this act of reunion as restorative, healing. A ritual is something to be done with intention, with meaning, something symbolic, oftentimes sensory-based. I wanted to create a space that would host a ritual without a script. This translated into a room that held potential for many things, filled with plinths that hold vessels containing berries, water and wine. The most obvious invitation was to eat and drink from them, but everything else would be allowed. I liked the idea that anything happening in that space would be a ritual. When I showed this project in Hamburg, the exhibition happened to coincide with the passing of a comet for the first time in 50.000 years. This added a whole new layer to the work.

As the origins of prehistoric rituals were often associated with astronomical events, it seemed like no accident that the exhibition coincided with one of them. The comet had passed by the Earth for the last time in Neanderthal time, before mankind, and just like that, it was passing by again, giving us the chance to create a new ritual in its honour. I felt like it reinforced the cosmological opportunity for us to start new, to create new stories and to see the world differently — which is what the work is all about.

You have referred to the fact that silver is the metal linked to the moon, the feminine and all that is mysterious, and have quoted an extract by famous feminist and sci-fi author Ursula K. Le Guin on Instagram. Can you further explain the exploration of femininity in “Sideros”?

I think the work carries an attempt to reinterpret what it means to be human, perhaps through a particularly feminine point of view. An exhibition visitor pointed out something that I could have never put into words: “hope and anger, pain, sadness, but also strength, and a lot of femininity”. I had never thought of it that way before, but I think it is definitely there. I believe the work invites to be present, also in our vulnerability.

When I started this project, I was writing about human connection and separation. The reflection revolved around the idea that there is strength in vulnerability, and that perhaps the boldest thing we can do is to accept our limitations. Being present as part of a community is also about showing up authentically, or at least it should be. I think we lack a lot of that as a civilisation, needless to elaborate on why.

The beautiful text “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” by Ursula K. Le Guin deeply relates to this. Even though I only read it afterwards, I felt like it was written for me, for this project. I was impressed by the way it describes the beginnings of humanity as gatherers, not hunters, and goes on to recognise the conflict-based narrative as the key factor that led history down its violent path. For months, I had been lingering on this idea: that we made our stories but afterwards those stories made us.

Considering you investigate storytelling as a way to contest dominant narratives that have shaped societies throughout history... Does “Sideros” put forth a utopian vision of the future? In what ways? Is there a space for science fiction in your work?

This project spanned over a year, so it accompanied a few changes of perspective. The further I researched a certain topic, the more I realised that there was so much more to it, so many other perspectives. I had to zoom in to then be able to zoom out and look at the whole picture. That was when I realised that I wasn’t merely researching myths and stories, but was rather trying to understand something present and real: who we are, what we have in common with our ancestors, what separates us from them, what we can learn from that correlation.

I was trying to understand the present in connection to the past. Thus, it comes from my perspective, reflecting my personal background, beliefs and struggles. That’s why it can be considered critical, challenging, political, or feminist, and, even if I didn’t intend any of this consciously, I recognise it’s there. I realised that Sideros is coming from a place of not being able to accept the future ahead of us. The uncomfortable truth is that reality becomes more dystopian for me by the day. It's hard to imagine a future in real life, now more than ever, so I guess I try to do it through my work.

In that sense, the work primarily challenges the idea of science, technology and progress altogether. By proposing to go a few steps back and to reconnect to a more honest way of being human, it contests the idea of a technological-progress based future. Then, It also defies ideas of strength, masculinity, power, and conflict. I am very interested in deconstructing the idea of the Hero, which is deeply related to all of these attributes.

With that being said, there is definitely a part of me that wants to propose a better version of the future. However, I can’t say there is space for science fiction. I would say it is the complete opposite of science. It’s rather a human fiction. Also, the work doesn’t really claim to change the world, it only suggests a moment of pause, in which it is possible to ask question and to have these conversations, and from there to perhaps create something new.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 21.11.2023