AS TIME GOES BY

Lisbon-based artist Monica Coelho awaits me in her studio, a flat full of light situated in a narrow street overlooking the knotty neighborhood of Martim Moniz. From her balcony, she points at the two buildings that oppose her own, confessing that she often sits to listen to the neighbors chatting from one window to the other; the kind of tender, comical detail that somehow summarizes her artistic interests and style. It’s easy to tell that she is one observant artist.

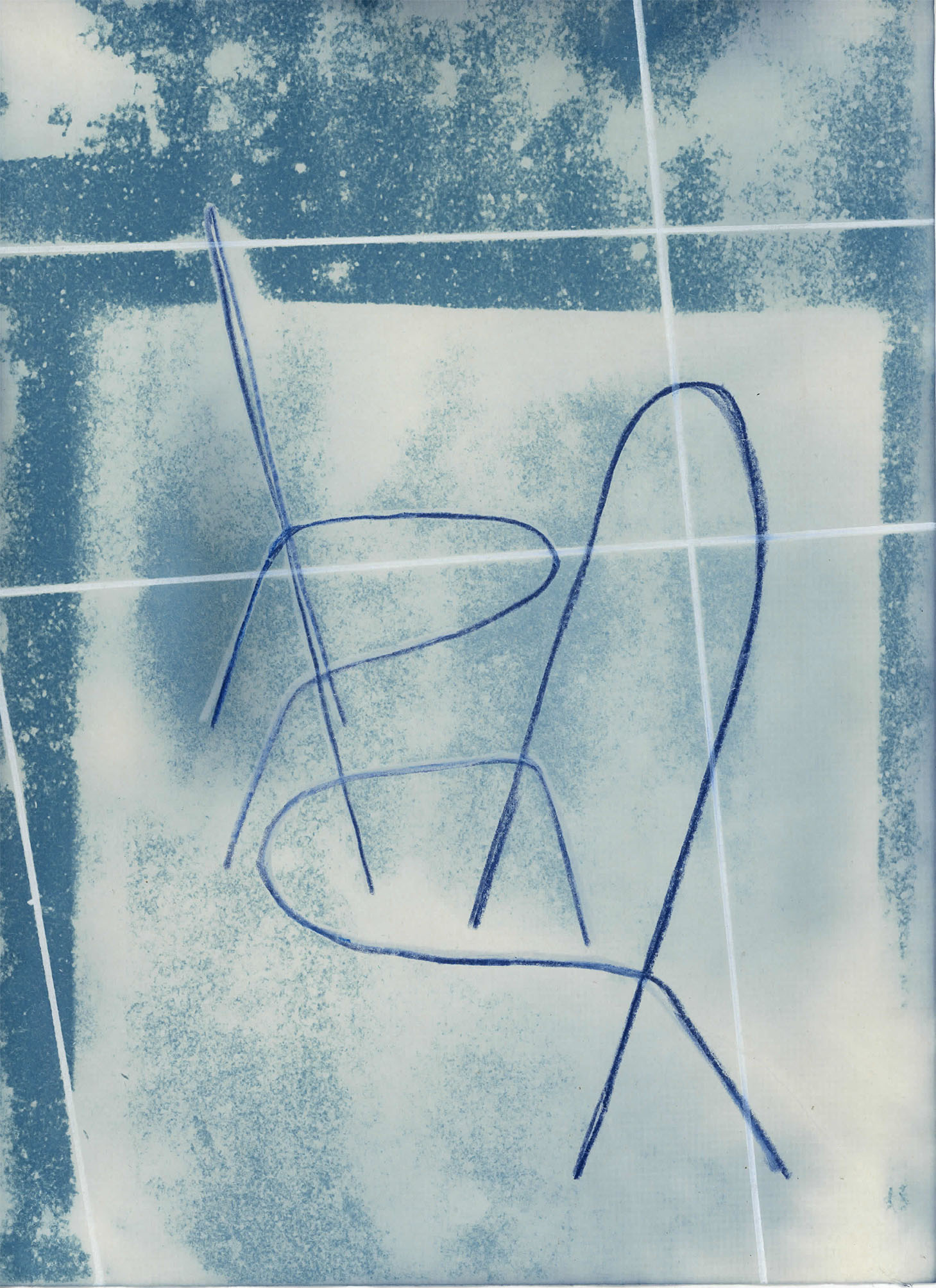

After a few minutes, Monica starts to bring out one drawing after the other, delicately presenting them before me and hanging them on hooks stuck on the walls, where they are softly pushed by the breeze, brittle like paper planes. I am struck by the lightness of the paper, the trace, and the choice of bleached blues, smoky blacks and intense reds that create subtle contrasts on the white surface. Her practice seems all about matter, repetition, and technique. But when I enquire about the origins of her work, I am amazed by the funny-comical-ironic bundle of anecdotes and impressions that come out. For example, that artists have sent works to the moon in collaboration with NASA! (An option that Monica does not rule out for the future). What else? Well, also varied thoughts on anthropology, design, chairs that talk, shortcuts in bus stops, trips from Caldas da Rainha to London to San Francisco… Reflections on longing, and waiting, and absurdity and belonging, and, essentially, a constant questioning of what exactly it is that makes us human.

I worried her uniqueness wouldn’t come through in the written replies, but thankfully, it did:

I have parts from those professions in mine (and in mind).

I find in art the same freedom that attracted me about being an astronaut. (A work of art might take a lifetime to complete). I also search for cures, like doctors and activists. I discover and fight injustice. I do care about how the human body functions and its limits.

When I applied to college, I applied for 6 different things: Anthropology, Painting, Sculpture, Social Studies, Visual Arts and Urbanism (not in this order). I still think those are some of my biggest interests. I am very interested in observing how people live. And I believe that urbanism, space and site are a powerful way to direct how people behave in a city. My work residencies have been a great way to see new places and discover other realities. I would say I am a soft activist these days.

You come from Lisbon, but studied at Escola Superior de Artes e Designdas Caldas da Rainha, and afterwards did an internship in IKLECTIK ART LAB, a music gallery in London, and an MFA in Studio Art at San Francisco Art Institute. Being interested in how lifestyles vary depending on territories, have you found these changes enriching?

Yes, super enriching. Being a foreign somewhere is a great way to question everything. Everything is new, and a lot more things do not seem to make sense at first. That, for me, is a great way to start thinking and working.

It also affected and informed my work. In London, for example, everything I did was small, since I did not have a studio or a lot of space. And the drawings made there are colorful but very empty. I believe this happened because London was full of people and very gray (I was there from September to February).

I moved from Sintra to Lisbon when I was about 5 or 6. These are very close, about 30 km from each other, but completely different. In Sintra, I used to run from school back home alone, as there were no roads and not a lot of people in the streets. In Lisbon, on the other hand, I had to walk on the sidewalk and hold the hand of one of my parents. There is much more light, more noise, more people, etc.

London, for example, felt like a capital of the world. There were people from everywhere and each person had their own accent. Most people were passing by, even if it was for a few years to study or to work. Things changed really fast. And everyone is very organized. Everything is planned in advance, as people live so far from each other and from the center. You cannot call someone and say “let’s get a coffee”, as they might be 2 hours away, and they drink tea. Time is a precious thing, most food is sold already cooked and ready to eat. People were nice but distant. Coming from Caldas da Rainha, where everyone says hello to each other on the streets, where you can walk everywhere and you don’t need to make plans, you just meet people in the park, the square or the beach… It made a big difference.

In San Francisco, I met people from all over the world. Most people work in tech, so everyone is thinking of the future and testing new ways of living. Many people only work four days a week, they enjoy nature often, go on walks, and go camping most weekends. They are also very focused on health. They eat well and most people exercise.

They are also very proud to be in a city where people read books. The buses are electric and many people bike everywhere, even though there are hills. There are recycling and compost bins everywhere, and everyone carries a reusable bottle of water. And they have been there for some time. At the same time, it’s history is of a very open-minded and acceptable city for everyone. So there are a lot of homeless and a lot of them are mentally sick. They still get support in many ways. The city is prepared for the very rich and the very poor. The hardest part is to be in the middle. Not being able to go out for dinner all the time and at the same time not being able to use the free clinics.

There is the culture that comes from a place’s history, and then there is how a city is organized and who lives there, under what conditions, laws, etc.

Your practice mixes a variety of mediums, including drawing, sculpture, video and installation. How do you settle upon one technique or another?

Sometimes a project asks for a specific medium, other times I am exploring one and a new work is born. I mostly and constantly work in drawing. Sometimes, the drawings ask to be sculptures and often become something very different.

Inanimate items populate your production: windows, chairs, newspaper holders, doors… Is there any characteristic all of these have in common? Can you further explain the symbology you imbue into them?

I became interested in the chairs as characters who were also waiting in the waiting rooms. Waiting to be seated on. They are sculptures and empty. No one can sit on them. I think they have to be set all around a room and just show how weird it is to wait. Like I did in the installation Waiting room, 2019. It’s like a revenge, I prefer to think the chairs are the ones waiting and not the people. After that installation, I saw the empty chairs as a seat to be filled, or a “no one”, and used them in other works.

I do love windows, doors, bridges and things that are in between. They are both and neither inside or outside. They are the line that defines a space. I also love structures, maybe for the same reason. They are the lines that define things. In the case of the newspaper holder, I like the structure and how, even though it was empty, it was still being set outside a newsstand every day. It was also waiting. It is an object of hope. Hope that one day Cachopo (the place where it was) will have enough people again that it will be worth selling newspapers there.

Your

practice is similarly traversed by an interest in the passage of time: clocks,

waiting rooms, seasons, changes in the weather, bus stops… I wonder - is this

linked to a sense of longing or melancholy?

Your

practice is similarly traversed by an interest in the passage of time: clocks,

waiting rooms, seasons, changes in the weather, bus stops… I wonder - is this

linked to a sense of longing or melancholy?I think it started with the sensation that I was wasting time in a waiting room in the hospital, when I could be doing something more interesting. So, I started working while I was there. It was a way to feel like I was not wasting time.

I do have a constant sense that I am late. Maybe it’s a Portuguese thing.

Which reminds of a time, during the master degree in the USA, when I asked some friends to come to the studio and help me choose works to present in an important evaluation. During the visit, I realized the evaluation date was two weeks away and not one. One of my friends pointed out that he had heard before that Portuguese do not understand time. I immediately clarified that we do, we just think we are always late, individually and globally. Another friend immediately asked if we, the Portuguese, are in fact always late. I said yes, followed by a no. By this time everyone was laughing. I clarified once again, we are not super restricted with time, and, if everyone is late, then, no one is.

San Francisco had no seasons, unlike Lisbon. The sky didn’t change, the temperature didn’t change, the trees and my clothes didn’t change either. And that messed with my perception of how long ago things had happened. So, I started to look for other signals of the passage of time, doing work that was affected by time or weather (in Portuguese time and weather have the same translation: tempo).

The bus stop intervention happened because, in San Francisco, bus stops have two glasses on their back and on their sides. The front one and a space in the back are left open. Which defeats the idea of a bus stop having so many walls and a seating to protect people from the rain, the wind and the sun while they are waiting. So I made a door to see if people would use it. Unfortunately, I was not brave enough to leave it there without me. I was afraid of physically hurting someone or getting a warning by the police, that would affect my visa.

I do like the idea of longing and hoping and saudades.

You are also drawn to movement of people in the street, and have filmed various videos recording this flux. How do these hectic pieces oppose your static ones? Do they all explore varying notions of immobility and motion?

It is an interesting question. I think everything is in motion all the time. Even the things that seem to be still are aging. But I do like that idea of immobility. During the pandemic, I discovered the piece Shrink, made in 1995 by artist Lawrence Malstaf,which shows people being held in plastic like food in vacuum. And one of my favorite songs is I want the world to stop, by Belle and Sebastian.

The idea of registering a specific moment, preserving an object or feeling, and stopping time are common interests of artists and humans in general. It is said that the first sign that humans were different from animals was when they (we) decided to bury the dead. In this way, we are preserving someone’s life, and leaving/bringing them to the future. And those constructions can be looked at as the first sculptures.

Is there a place for irony and humor in your practice? What attracts you about certain random situations that appear in your video art?

Yes, there is always space for humor. Those images are all real. And reality can be funny.

The collection of people wearing pink and black is a work for a project by artist Marta Wengorovius. She put together a group to think of the idea of MANY (the community). The premise was to consider whether the pandemic has suspended the idea of the MANY or not. I believe it brought the world closer. We now have more history in common. I do wear pink and black for a job where people are supposed to easily find me in the street when they are lost. But I notice that there are a lot of people wearing pink and black. Which makes me think we share more than we know. I think it is a sign of how close we are. Maybe it is a trend of our time, or maybe, the fact that there are so many people wearing a seemingly easy outfit to spot, speaks about our wish to be seen or be part of the community, the MANY. This project is not finished to this date.

In the case of the video of a family sharing cake over recordings of a soccer match, it is also a recent project. I had the video first. I thought such a calming image of a family sharing a cake would become stressful if put with a sound from a very stressful game, such as the final of the world championship. I thought images depended on the narrative attached to them. What happened was that the video became funny and not stressful. In the game, they speak as if they are talking about the most important day of the century. They say things like “this is an important day in history that forever will remain in our memories…”

I worry that there is too much control over images we see daily. So I prefer to look at reality. To represent is to show instead of just be. I want to know what actually is. I also think reality is absurd and funny and scary enough. Of course that what is shown is a perspective of reality. It is what I have seen. I also like what is rarely seen, but right there. That is another reason why I like to work with transparent materials and ideas and do site-specific, to work from what’s there and for what is there. To observe is an important exercise.

In the installation A lack of presence in the present, 2020 there is a video that shows the view of the window standing next to it. In front of it, I put a sculpture of an empty chair. No one was looking at the view. But maybe it didn't need it, since so many people, who used that space everyday, asked me where was the place shown in the video.

Your installation piece “To meet another time” (2021) varies depending on whether the viewer sees it from the window or from the inside of the room where it is hung. Why did you settle upon this dual effect?

Yes, I did. I was invited by Light of Day collective to create a piece for a space that was not yet open to the public, due to covid restriction. The space was a bar. I liked that from the outside, even when the space is closed, one sees the hand still, like a mark inside a cave, of a former presence. Once inside, one sees another hand, hanging from the ceiling, dancing, present, and almost touching the other hand. Between them there’s a drawing of the outside space, on the window. The outside is reflected on the window into the drawing, on the glass. The inside of the bar is not accessible, nor is it possible to see it from the outside. From the inside, this drawing tries to guide the view of the window.

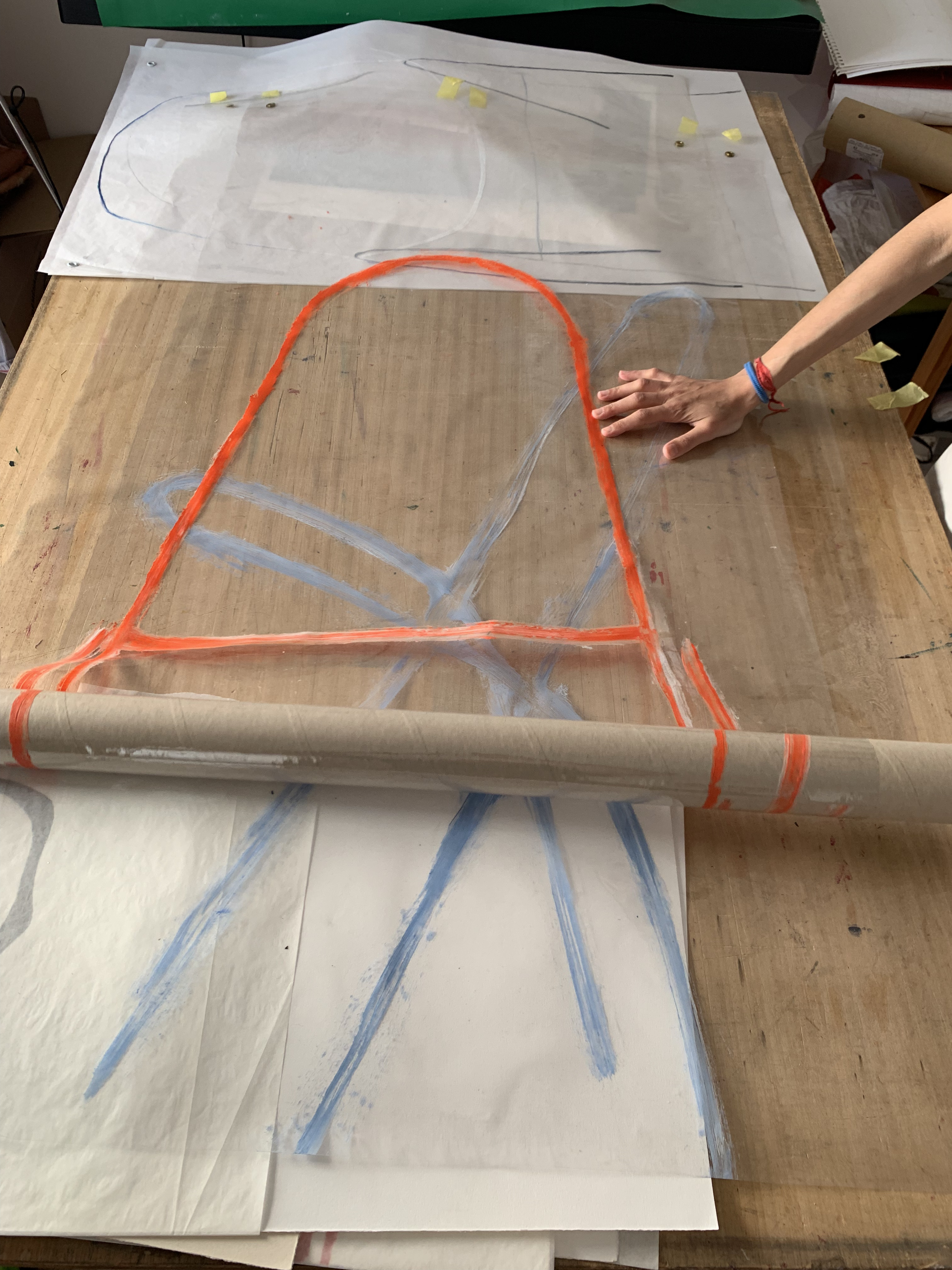

In your atelier, you showed me dozens of drawings showing slight variations, including ones that were the result of an “error”. How crucial is the process of creating for you, as opposed to the importance you give to the final object?

Often the process of making is more important and more interesting to me than the final piece. It was great to hear you say that as well, because it is something I need to be reminded of once in a while.

To make is already part of the piece. While making a drawing, I see something missing or I discover something new that brings me to the next drawing. That is why there are many similar drawings. In the case of installations, the making informs the final piece. For example, now I want to record light and shadow of the space where I am, using cyanotypes. I have no idea, though, what I am gonna do after I have those images, how will they look and if I will change them.

The last time I used cyanotype, it was making images about waiting. Cyanotype is a process that demands the piece to spend time under sunlight to appear, so the idea that I also had to wait for the waiting drawings was appealing. In the case of Weather clock (2019), the piece changes depending on the amount of rain that falls, since it was put on display on the rooftop. I think the piece is interesting while it’s changing and not as much at the end, once it’s fully changed.

I think that’s one of the reasons I like drawing so much. In a drawing everything gets registered. All the mistakes and all the dirt of passing your hand over the paper, even accidentally. And the paper is fragile and it shows marks of its handling, making.

Even in other works, I often admire when the action of making is the final piece. Like the walks of Richard Long and Francis Alys. It should also be said that that’s not always the case in my work. Sometimes I have an idea of what the final piece should look like.

You have participated in a large number of collaborative shows, as well as in projects such as “Conversas Lisboa”. In the future, do you see yourself being part of similar multidisciplinary projects?

For now, I really enjoy artistic residencies. To go somewhere new with a group of artists for a period of time has been a great way to work and live. I would love to go on longer residencies that are even further away.

I would like to have more courage to leave pieces in the street.

I would like to work with specialists or researchers in other areas that are interesting to me.

And continue to do what makes sense.

Interview by Whataboutvic. 10.07.2023