A BALMY TOUCH

It is hard for me to introduce London-based artist Hannah Archambault. An infinite amount of conversations come to mind. From late night philosophizing about love, light and touch, passing through discussions on the effects of labor, loss and grief… All interwoven with chit chat over dinner, dark wine, roasted aubergine and lots and lots of poetry. I guess all of these things traverse her practice, but I am probably missing many more.

I can recall the first time I interviewed her, in Lisbon, where she spent the months of February and March of 2022 as a resident at Duplex AIR Residency. We talked for hours over hibiscus tea, one of the materials most present in her practice. Hannah let the brittle leaves dissolve in the water and urged me to observe the red tint of the liquid. She usually has such an eye for detail, for all that is manual or raw, and the excitement to share it with someone close - “That shade of red, my god!” Nothing else decorated her studio, except for a volume of “All About Love'' by Bell Hooks, and her characteristic leopard jacket, loosely hanging from a chair. A bare and bold and blissful scenario, where not much else was needed. Just some sun and a space to talk, hot brew to dissolve in and feel the slow paced, balmy peace of sensing, and connecting, and being.

I saw it then as I see it now. For Hannah, little is enough. The most important thing is what lies beyond, and within. Beyond sight, beyond touch, within oneself, within others, in the gap between what is perceivable and what is not. As always when we talk, I drank down her replies in a strong yet supple sip. Here’s a taste of it:

Hey, Hannah! After completing a degree in Photography at Les Gobelins School of Image in Paris and an MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art in London, you moved on to produce ambient installations and musical pieces. What caused this change?

I believe that everything is connected. So, in some ways, photography brought me to spatial installations. I was intrigued by the gap between what is observable or tangible in an image, and what is unperceivable in it. This grey area was explored further in my work “Exposing Emptiness”, where the exhibition spaces I captured seemed to come from a different environment: somewhere lying between the fantasied, the real, and the virtual. I liked that we could feel confused about these aspects, not being able to decipher the boundaries between them.

But the more I investigated about space, the more I wanted to build my own. I was longing to invite audiences to step within the piece, to be a part of it. To lead them towards experiencing it with their whole body, and to raise questions by making them trust their senses.

I was also questioning myself on how a space affects us on a bodily, emotional, physical, and psychological level. Photography was not the right medium for that for me at that time. That’s why I decided to move towards sensory installations, using space as a medium, and sometimes even starting from it. Moreover, I was willing to better engage my body in my practice. Listening, moving, touching. I was starving for that.

At the end of my Bachelor in Paris, I was lucky to have a large place to exhibit my final show (Thank you Prep’art!). Within it, I discovered a room that I could transform into a dark-room. A room where people could embrace the space physically, beyond the visual quality of my photographs. On entering that room, I pictured it being enveloped by a sound installation right away. It is funny because it often happens to me: I feel an instinctive and vivid response manifesting at the very encounter of a place. This is why I consider my installations being site-specific. They would never be the same somewhere else. The construction of a piece responds, shifts or becomes in tune with the space it is being developed in. It encounters , its history, its light, its smells, its sounds, its scale, its temperature, its use etc.

All the components of a space play a role in the work, they become a part of it. So when I had that space, I started to delve into sound even though I did not have any clue of how to compose music.

I began to record sounds outside, and asked a friend to use her voice, and eventually melt the sonic elements together. They were layering the space, as I had gathered several ones into one. And I fell in love. Later on, I dived into composing sound at the Royal College of Art. I put myself there, and met the sound technician who helped me with the basics of Logic Pro’s sound software (thank you Tim Olden!). Things were taking shape more and more everyday after long days of work. When I become obsessed with something, it really can’t leave me, haha. Field-recordings and voices sew the seeds of my sound-making, through my using them as instruments. They built a sonic space that intrigued me, being intimate and open at the same time. I discovered how invisible and yet hypnotizing sound is, finding a sense of absoluteness while composing.

You have repeatedly associated hibiscus with femininity, and salt with friendship. Can you guide us through the process of relating each material to its corresponding topic?

Sure, thanks for asking! Glad to guide you haha! The materials I use and the interpretations associated to them have to be meaningful. The first encounter I had with hibiscus was through taste, by drinking it. I loved its acidic and « dusty » taste, and was intrigued by its hypnotizing redness. It seemed to be calling me, and I got aroused by it in a way. I wanted to know more about it. Amongst its history and virtues, I have discovered that hibiscus flower is recommended as an infusion to help relieve menstrual pain. It resonated with me for that. As I was —and still am— exploring feminist questions related to gender inequality, I choose hibiscus flower for its symbolism as a female marker.

I am interested in picking materials rooted in historical or symbolic origins that resonate with the themes I am probing. I tend to be first allured by the material for its colour, smell or texture, and then I start researching on its myths and stories the trajectories and locations it went through time. The best places to discover them are spice shops in London. It’s like entering into a multilayered place, a place containing several ones inside, each very exciting to encounter. I like the idea that salt, for instance, is very present in our daily-life, and can even be a part of us as we eat it, and yet we don’t know its stories.

Thus, I have examined its origins, how many lives it has held, and how precious its nature could be. Somehow, it is about giving the material a different charge, making it sacred, or giving it back its value.

Salt slipped into my interest at the same time as I encountered the proverb ‘Amicitia Pactum Salis’, meaning ‘Friendship is a pact of salt’ in latin, indicating that we share salt and food with our friends. It also echoes the sacred quality of salt in the Middle-Age, which was then was costly and rare. On another note, salt is used to keep food alive by preserving it. Thus, salt symbolizes this solid bond of friendship, something we do not break easily. I really connected with that, and now each time I want to introduce bonding, a contact or talk about relationships, salt is in my mind. It doesn’t mean that I would use it systematically, but it is there. In Pactum Salis, I covered an entire floor of a room with salt (700 kilos actually, what an adventure!) and invited people to remove their shoes, step and roam on it., bonding through the ‘sacred floor’. In a way, they were connected through salt, each of them being in direct contact with it.

Despite the meaning I breathe into the materials I use, these are carried away by other people’s interpretations and stories. And this is beautiful. The public establish their own relationship to them.

You manually manipulate these natural mediums, as well as textiles, and invite visitors to interact with them. What is it about their organic nature that you find sensual?

I find them sensual for their appeal, as if they were holding a secret. They all spur us to come closer, observe, smell, touch, wanting to taste; something primary takes place. They are ambiguous. In some ways, even though we get seduced by their appearance, they remain ungraspable, eluding us. The opaqueness produced by the salt covering the floor of an entire room generates a feeling of absoluteness, a desert of peacefulness. The hypnotic color and texture of hibiscus infusion makes us want to drink and touch it, even though we don’t know its nature, or if it is allowed or even drinkable. The familiarity and intimacy we reckon from the bed sheets attracts us to touch and smell them, even if they have been displaced from their initial locations.

I like using sensuality to invite people to step within this confusion and experience a tension between two states.

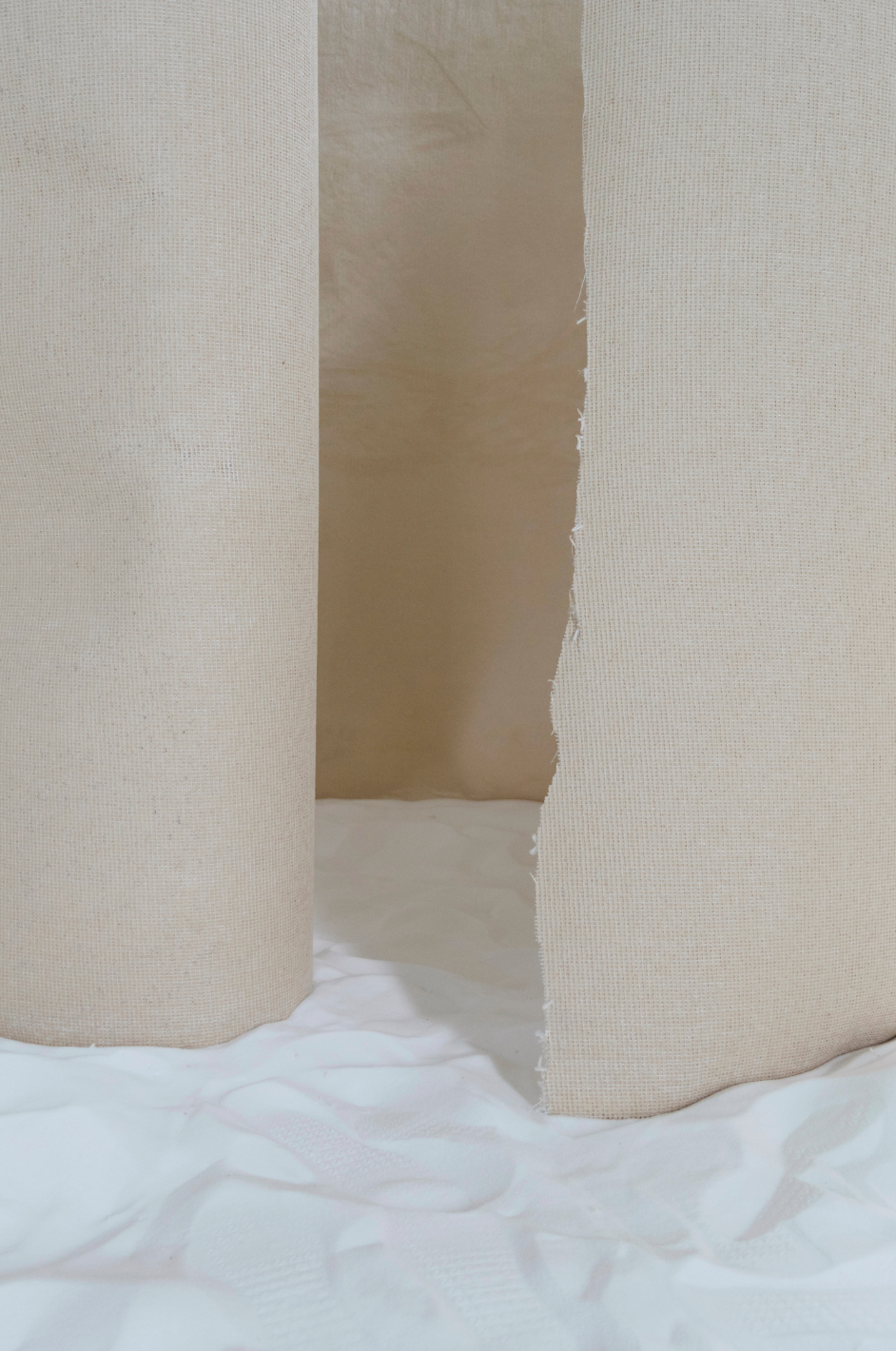

It is also meaningful for me to choose elements that were part of a moment of intimacy before, and that have been charged through it. Something personal gets to live in a public space. If I had found bed sheets or curtains in a generic shop they would still smell of plastic and would have belonged to no one. The curtains from the house in Lisbon had been there for since several generations, having been touched by different people inhabiting the house. I love the invisible lives and gestures they hold.

In “Embalming Anger,” (2021) you weaved dry hibiscus into chains as a way of metaphorically transforming feminine anger, represented bt this herb. Is there an element of performativity in your procedures?

Actually, there is! The hidden gestures in the making are part of the art piece too. Sometimes it’s invisible to the public, sometimes it’s a statement. I often involve my body in acts of care, repetition and slowness. Something takes place through these gestures. It becomes like a ritual, as if entering into an entrancing or meditative state. When I pour the salt on the floor, I do it with extreme care. I want to hear the salt sinking, to see it piling on the ground.

So there is definitely an element of performativity in my pieces. I am also attentive to setting up a frame, and particularly dedicated moves.

With "Embalming Anger", I was looking to overturn the usual behaviors and signs associated with anger (such as aggressiveness, loudness or violence), by highlighting the possibilities of an anger that is cold, dull or veiled. By taking it to the polar opposite, being soft and thoughtful, I wished to process female anger and transform it into something else. To try to understand it, dissect it like a nutshell. To tame it in a way. And ultimately, yes, it became healing.

Is it important for you to react physically to the space where your works are to be situated? Which environmental factors do you give importance to when envisaging a new piece?

I like the idea that art can be experienced bodily and sensually. Then, if it raises questions or reflection, it is even better. But, in a sense, the body knows, it has its own truth. I care to introduce different layers of understanding within my work. The sensorial tends to be as open and as possible to everyone (children, old people, etc). The conceptual and interrogative ones are there for people who want to dig deeper. And, yes, I want us to move inside an art piece, to touch, be touched. I wish for us to reconnect with our bodies, and I believe that art can be a bridge towards it.

If I can, yes, I visit the space before developing a project in situ. It is actually a very exciting moment. Where everything is still possible. I try to consider all the characteristics of the space, but I guess some of them slip away from me… Its identity, its use, its colour, its light, its smell, its size, its boundaries, its history.

For whom was that space designed for? How to break that? These are also questions I ask myself.

At Duplex AIR in Lisbon, where I was a resident in early 2022, I discovered a space that looks like a bathroom. That space in the residency was the only one that seemed to be closer to an intimate and personal one, as it came from a domestic place. This parameter stayed with me, and I started a project from that.

In “Linger on me” (2020) you constructed a reduced corridor where visitors could meet. Was it your goal to generate a feeling of shared intimacy by limiting the available space? How are private and collective modes of behavior examined in your practice?

I was very intrigued to see what could arise from an encounter between two strangers in a narrow space. I was wondering: How is it to sha

re an intimate moment with a stranger? Is it possible to feel close to someone we don’t know? How could I shift a potential awkwardness with a stranger in a small space to a shared moment? Can we bond through listening? Can we be OK with waiting and being attentive to the other in front of us? All these questions were part of Linger on me. The piece was built along with a musical ambient piece of 13 minutes with few changes, meant to prompt the participants into a more careful listening.

The sound piece was set within the narrowed carpet space, so that you were listening to the sound piece, touching the feeling of the space if you wanted, and were very close to the other person in front of you. The two people entering inside were also hidden from the others. It was about them, nothing else. I got inside too, as I was curious to put myself in the skin of the visitors, and it was very intimidating or warm, sometimes both. From one encounter to another, things were very different. The two participants have to be open to let the piece grow within them and see what occurs. Things also happen through time. If you stay there only five seconds, you would not be able to have the same experience as if you stay there three minutes. But a shared gaze, a proximity between two bodies, it still creates something singular.

In your book “On the Edge of Fantasy,” (2020) you asked participants about their vision of fantasy and the role it played in their daily lives. Are you intrigued by the transformative power of reverie?

Yes, I see it as a tool to escape but also as a way to connect with ourselves. What is transformative with fantasy is that it navigates through desire, and often involves sensuality and touch, even imaginatively I mean.

I would love to bring more affection, relationships and womanliness into our daily-lives! I am still very sad and surprised to witness that many things from our economical, political and social systems and so on, are ruled by power, privilege and money, and that this invades our personal lives. They are both very interwoven, but in a sneaky way, you know? It is very invisible sometimes. So, yes, it would not hurt anyone to give and receive more care in the environment we are living in.

“She Breathes the Cold Water In,” (2022) was developed after the poem ‘The Queen of Denmark', by writer Margie Orford. Are you drawn to the liminality or subtlety of poetry? What other references have informed your methods?

The pleasure I find in poetry is about its texture, but also because it leaves a lot of space to diverge. You invest your own experience into it and feel. The voice of Hannah Walton was also key for me to compose the sound piece, and was the starting point of this installation. I imagined her low voice in it right away. It set up the base of strength and warmth I was looking for. The space the artwork was displayed was crucial too, as we decided with curator Francisca Portugal to envelop the audience in orange light. Orange is often associated with spirituality, and with sunsets a more mainstream way.

So they became a frame or a guide as much as poetry, the voice and the emptiness of the room: enablig bodies to take the space.

Can you guide us through the process of transforming an individual circumstance of laboral anguish into a broader exploration of precarity in one of your latest pieces, “Without Milk” (2023)?

When I started to work as a barista in London, I experienced difficulty and anger towards a job that was draining, until I said to myself that I had to do something about it. The coffee grounds were the leftovers, the traces of the work my colleagues and I were providing, and they became an intriguing source for me. I liked their texture, their acidic smell, and their charge. Indeed, they were soaked in our collective sweat, being the result of our physical labour. The position of being a barista is very repetitive, demanding you to walk a lot and never really pause. You are constantly surrounded by noise and pressured by deadlines. It is a profession that is usually paid th

e minimum wage and is not recognized, similarly to the role of a cleaner or a store seller, among many others.

To me, the personal always has been political, and it is out there, in our daily life. So I started to collect that material. With time, I realized that everything was already there: the coffee grounds were strong enough — symbolically and sensually —, to be exhibited in a room without any other element. They were breathing on their own. I wanted them to invade the space, as they were symbolizing our hardship. The idea of collectiveness came about through the decision of asking the baristas of the cafés in London to merge my work with theirs. The piece became about our collective labour and precarity, the ways to survive in the city. In the end, the piece became open for the public to walk on the coffee grounds. People were invited to remove their shoes. Thus, that labour I was talking about was exposed, a space was dedicated to it.

So! Last but not least… What does the future hold for your practice? Do you have any wild dreams or aspirations? Would you be keen to continue exhibiting in public spaces?

I would love to compose music for animation movies or films. I find the mix of moving image and sound quite challenging to balance, in order to reach the right place. There are different ways of blending these elements, such as aligning them or creating a break from one to the other. It would be very inspiring.

I would love to keep exhibiting in public places! I am drawn to ways of dissolving the boundaries of space in terms of who can access it, and who is less welcomed to get in. I would like to see children, old people, and the less privileged ones to be more taken into account. It is also exciting to see them get involved, and to witness them branding a slice of life to the art work, and the art piece becoming alive through them.

Words and Pics by Whataboutvic